Journalist Suki Kim’s Book on North Korea Was Marketed as an Eat, Pray Love Memoir

In 2011, investigative journalist Suki Kim, went undercover as an ESL teacher at Pyongyang University of Science and Technology where her students were 270 sons of high-level officials. She lived in a locked compound for six months and, under constant surveillance, wrote in secret.

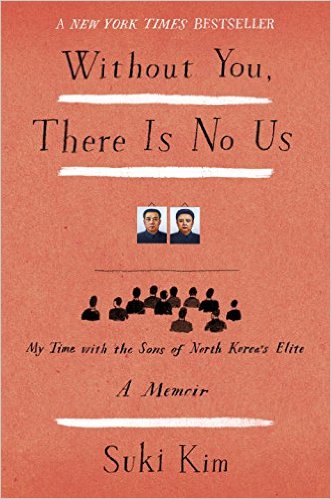

In a piece for New Republic, Kim wrote about how her book, Without You There Is No Us: My Time With the Sons of North Korea’s Elite, was labeled a memoir rather than journalism and how the ensuing marketing trivialized the work she did. She writes, “by marketing me as a woman on a journey of self-discovery, rather than a reporter on a groundbreaking assignment—I was effectively being stripped of my expertise on the subject I knew best.” Kim recalls one interaction, where she asserted that her work wasn’t about memory or “how [she] saw the world.”

I tried to push back. “This is no Eat, Pray, Love,” I argued during a phone call with my editor and agent.

“You only wish,” my agent laughed.

While there is nothing wrong or less compelling about memoirs (although there’s plenty wrong with Eat, Pray Love), Kim’s goals, intentions, and undercover work were journalistic in creating Without You There Is No Us and ignoring her profession for sales (memoirs sell better) comes across as patronizing. She cited the code of ethics from the Society of Professional Journalists, took measures to ensure her students would be safe, and conducted a decade of research. This shift from journalism to memoir is more indicative of how she was “being moved from a position of authority—What do you know?—to the realm of emotion: How did you feel?” something that Kim says should feel “familiar to professional women from all walks of life.”

This mislabeling had other consequences as well. When Kim’s book was released, critical readers accused her of writing a “kiss-and-tell memoir” and dismissed her as reckless, unreliable and deceptive for endangering her former pupils. Kim points out that this is ironically the kind of fieldwork and narrative “that typically wins acclaim for narrative accounts of investigative journalism.” At events, audience member, “often white, often male, inevitably hostile” would challenge her work and tell her North Korea wasn’t as bad as she said or say she, a woman born and raised in South Korea, “had merely returned ‘home'” rather than undercover.

Kim, “a woman of color entrenched in a profession still dominated by white men,” had her position constantly questioned and dismissed as too personal, emotional, or deceptive. Her work on North Korea provides a perspective on a subject mostly written about by detractors or visiting white journalists. If you think through your armchair international affairs brain that things are actually “not that bad” and your first reaction to a book like Without You, There Is No Us is to call Kim a liar rather than examine what kinds of narratives we might be missing, well, you can take all the seats. The access she was able to gain and her own experience with the language should be something we actively look for when we read about North Korea. Additionally, when people embark on fieldwork or undercover work, it’s really important to consider what kind of access you have to that group of people. Do we yell at white men writing about other white men that they’re not impartial enough and just returning amongst their kind?

I recommend reading her entire essay here.

(via Jezebel)

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com