SXSW Makes Progress With Anti-Harassment Summit, but There’s Still Room for Improvement

In the ye olde age of 2015, SXSW got in some hot water for their decision to cancel two panels related to online harassment and gaming culture—one explicitly on how to overcome harassment, and one that listed “the journalistic integrity of gaming’s journalists” among their topics of conversation, so guess where that one falls, ho hum—after they received violent threats from people who were very “HOW DARE” about … umm … some other people saying,”Hey, maybe we should talk about these violent threats happening on the Internet.”

It’s a very, very special breed of stupid going on.

In the wake of the anti-harassment panels’ cancellation, people pointed out that, hey, maybe this means it is even more of an excellent idea to start a discussion about the realities of Gaming While Not a White Dude. Lo and behold, SXSW listened, announcing not one but a whole day of anti-harassment panels set to take place at this year’s SXSW.

Message to trolldom:

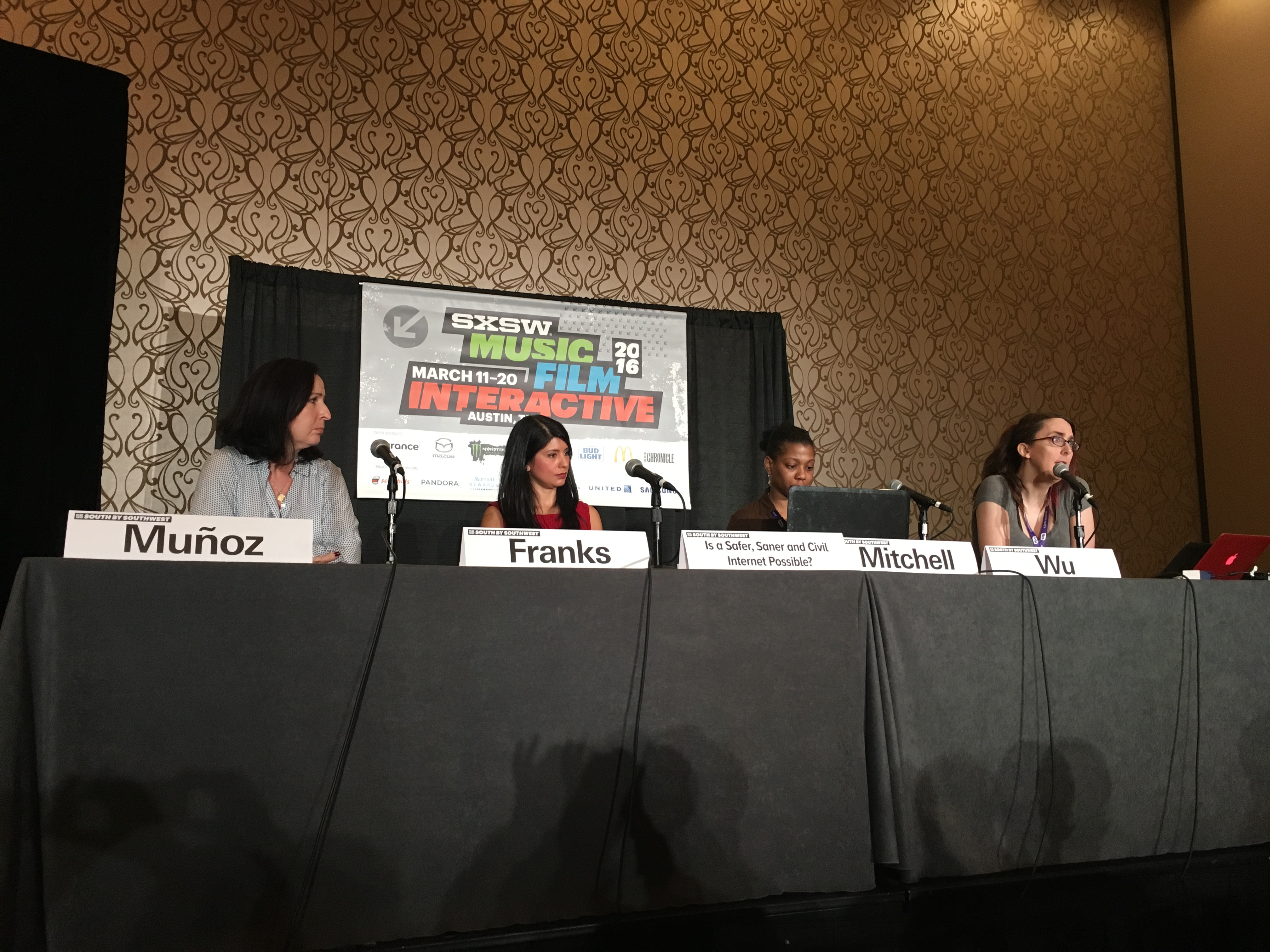

There were 15 panels total, giving SXSW a whole day of sweet, sweet #SJW action, with topics including “Profiling a Troll: Who They Are and Why They Do It,” “The Economics of Online Harassment,” and “Level Up: Overcoming Harassment in Games,” the panel that was originally going to take place at last year’s SXSW. I attended “Is A Safer, Saner and Civil Internet Possible?” moderated by Brianna Wu and calling on the knowledge and experience of panelists Elisa Lees Muñoz, Executive Director of the International Women’s Media Foundation; Mary Anne Franks, a Professor at the University of Miami School of Law; and Shireen Mitchell, founder of the non-profit advocacy organization Digital Sisters.

First, the positive: The panel itself provided a very spirited, informative discussion and benefited from the different areas of expertise held by its panelists. Franks, for example, is an advocate against “non-consensual pornography,” better known by the nom de ‘Net “revenge porn.” Mitchell spoke passionately about the intersection of sex and race as it applies to online harassment, while Muñoz’s specific area of interest is how sexual harassment is a frequent tool used to silence the voice of female journalists. Media, she argues, “is not truly free without the voice of women.”

Wu was very careful to note that this would not be a panel specifically on GamerGate, but one on the wider issues of harassment in online spaces, of which GamerGate is a (particularly loud, particularly obnoxious) symptom. Even before GamerGate thrust its stumpy little fingers into the world, the issue of online harassment was already a serious one: “Like the water pot was boiling and the kitchen was about to catch on fire.” As Franks noted, people in power—white men, cough cough—violently lashing out against progress is nothing new. In 1838, a building full of female suffragettes advocating for sexual equality and the abolition of slavery was stormed and lit on fire by a group of men concerned about women and POC knowing their place jobs and the Constitution. Yeah, totally.

“What we’re looking at is quite literally silencing techniques,” Franks argues. “We’re so afraid of what women might say that we have to do everything in our power to shut them up, and what we’re seeing now is the online form of that. And non-consensual pornography is just one of those ways we shut women up.” The online conversation about non-consensual pornography, she added, tends to focus on white women more than women of color: “We all know about Jennifer Lawrence” and her leaked photos, but vastly fewer people seemed to care that the same thing happened to Gabrielle Union.

Wu, who has a personal knowledge of online harassment rivaled by a small handful of unlucky compatriots (not a distinction you want to have), spoke to social media. Twitter has actually gotten better since GamerGate broke out in 2014, she argued; back then, the odds of successfully getting a harasser suspended was around five percent, and now it’s in the neighborhood of twenty to thirty percent—still far from optimal, but hey, at least it’s not Facebook (“a very, very, very dangerous place for transgender women … Facebook does not protect transgender women at all”) or Reddit. “I can’t say this clearly enough,” Wu said. “Reddit is failing women in every marginalized community spectacularly.”

Of course, harassment against women is made even more dangerous when the dread specter of racism is added into the mix. An example is “swatting,” or the act of calling the police and claiming that a (completely false, natch) shooting is occurring in the victim’s house, with the aim of getting a SWAT team to show up. “We need to look at issues that have a disproportionate difference for a family of color. If someone calls the cops and says there’s an active shooter, for a black household, it’s a very different thing.”

“Different” as in “oh, wow, this action that some people defend as a harmless prank could actually get people killed.”

And now, for the bad: This is less about the content of the panel itself than its organization—namely, that it was so far outside of SXSW proper that I’m only 70% certain I wasn’t in Louisiana. Granted, a lot of SXSW’s venues, particularly for the film portion, are spread out, and there was, according to SXSW’s website, “a point to point shuttle between the Austin Convention Center and the Hyatt Regency [where the Summit took place] to service select programming at that Venue.” (I never saw evidence of it; I’m reasonably certain it didn’t end up in Narnia.) Transportation issues aside, the panel I attended was practically empty, which, given the fever pitch that the conversation about online harassment has reached nowadays, I was quite surprised by. I got up early. I was going to stand in a line. Except there was no line. What there was appeared to my eyes to be some pretty hardcore security; every single section of my backpack was checked, and there were police on the premises. SXSW appeared to take the safety of its panelists very seriously, for which they get an Emily Blunt’s Arms gif of approval:

The lack of attendance was apparently an issue at the other panels, too, and it’s something that several participants in the summit commented on via Twitter:

One can’t help wonder, too, whether having fifteen panels, with three running at a time, was perhaps not the best organizational decision. Look, I’m not saying this isn’t a subject that doesn’t merit fifteen hours of discussion, but I’d imagine that “Respond to Protect: Expert Advice Against Online Hate,” “To Catch a Troll,” and “Women in the Media and Online Harassment,” all three running at the exact same time, are going to have a fair bit of overlap, content-wise. Do five panels—one at a time. Promote them. Don’t ask them to compete with one another. Put them in a more central location, so the only people going to the panels aren’t ones that specifically seek them out. I’d be OK with a scaled-down conference in a smaller venue if it meant we had some techbro “Hey, I’m not quite sure what the deal is with this but I’m right here so I guess I’ll check it out—wait, WHAT what happens to women on the Internet? Wow, that’s really screwed up. I didn’t know it was this bad. I really need to try to change this” attendance on top of the “preaching to the choir” crowd I was a part of.

That said, even if things didn’t exactly go off without a hitch, SXSW deserves commendation for choosing to do this event, and on such a scale, at all (as Wu herself acknowledged). They committed resources to it, and that’s hopefully indicative of a continued interest in being part of the anti-harassment conversation in the years going forward. There are just a few kinks to work out.

And if there were free chips and queso in ’17, I wouldn’t say no.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com