Our Books, Our Shelves: The Fallacy of the Universal

I’m tired of universal stories.

Growing up, I was taught that the best books, the best films, and the best stories were those that were “universal” or had “universal themes.” It meant that there was something in that story—some essence of the “truth”—that any person on the planet could relate to. It began to ring hollow to me the older I got and the more I read. I had a strict, religious upbringing, and books—along with music—became my glimpse into the outside world.

Sometimes, it was uplifting. My lifelong love of punk rock and hip-hop comes from how much artists in those genres spoke to me when I desperately needed someone to understand what I was going through. To an extent, books did that, too, but more often than not, that was from books I found myself at the library.

When it came to the texts that were taught to me, I noticed a frustrating pattern: I couldn’t find almost anything to relate to in what I was required to read. I enjoyed most of the books, but at an intellectual distance. Crime and Punishment fascinated me, but it was hardly a relatable book for a seventeen-year-old in-the-closet Latinx kid. Candide felt more like an interesting slice of history than a book to me at the time I read it. The Great Gatsby was fun to analyze when I was first learning about metaphor and symbolism. We read Heart of Darkness, The Scarlet Letter, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Turn of the Screw … you probably get the idea.

Over the course of my entire public school education, I was assigned only three books by people of color: Bless Me, Ultima by Rudolfo Anaya; Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe; and The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros. Three books out of well over a hundred. (I was in multiple honors and AP classes, where we were reading 20+ books a year).

So, who were those books universally appealing to? I remember other kids hating Bless Me, Ultima because it “promoted witchcraft.” Those same kids had no problem with the witches in Shakespeare. One of my worst bullies said that Mango was garbage because “all books should have only English in them.” I didn’t have the language at the time to understand what that truly meant, aside from feeling it was wrong. Why didn’t universality apply to these books? Were they not timeless?

I often use a particular text to highlight this problem: John Knowles’s A Separate Peace. (I could write a whole essay on the textual and subtextual queerness of this book, which Knowles denies, but TODAY IS NOT THAT DAY.) I was taken to task by a teacher when I tried to argue the book wasn’t relatable to everyone. How could a bunch of mostly brown kids relate to the struggles of Gene Forrester at a New England boarding school? I came to understand what was being asked of us: we were to twist our bodies, our lives, around a default. It was assumed that we would relate to these kind of stories because that’s what was “normal.”

I’m not interested in a world where we don’t read these books. (Well, I could go without ever reading A Separate Peace again.) So, part of the solution is the approach to teaching them. Why do we insist on removing these narratives from their place and time? That information is actually deeply interesting! By saying that something is “universally” relatable or understandable, we reveal just as much about our own cultural biases as we do about the content of a book.

What I want and crave these days is specificity. I love a book that is grounded in a place, a time, an experience, a culture. I think of how you can’t take the Bronx out of Never Look Back by Lilliam Rivera; there’s no way to read Zoraida Córdova’s Brooklyn Brujas series without an appreciation for a vast number of Latinx cultural traditions across the diaspora; the work of Anna-Marie McLemore is impossible to divorce from explorations of gender and sexuality. They are specific things. And if someone who isn’t Latinx or queer or Puerto Rican enjoys them? Finds something relatable in them? Even better.

So, why is it important for fantasy to be inclusive of the Latinx experience? The easy, flippant answer is: Because it just is. The world we live in contains hundreds of millions of people who identify as Latino or Latinx or Latine. So why shouldn’t the work we write and read reflect that?

The greater point here is not that we shouldn’t be reading books by authors whose lives or books don’t fit neatly into our own. Rather, the reverse has been happening. Many of us who are not part of the dominant culture have been forced to consume work that often doesn’t even think we exist except to be tertiary characters, villains, or narrative pawns to further the story of the more “important” protagonists.

And look what’s happening now: We’re eschewing the stories and narratives we’ve been force-fed. We’re writing our own stories. We are imagining fantastical worlds. It truly seems like there are more Latinx people writing speculative fiction than ever before.

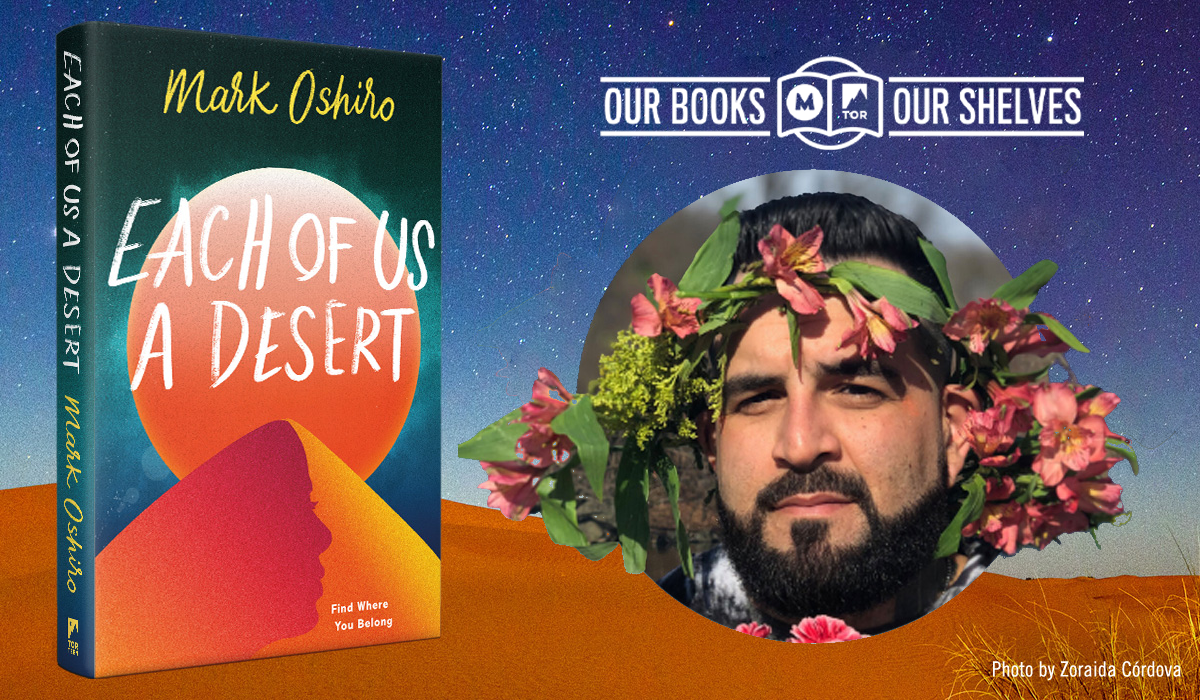

And there’s work still left to do, but I’m thrilled to be a part of this community, to be pushing boundaries, to be writing stories that are deeply, deeply specific. After three and a half years of grueling work, I get to release my second novel into the world: Each of Us a Desert. The book is a chance for me to explore my Latinidad in a fantastical way through a secondary fantasy lens. Initially inspired by my search with my twin brother for our biological father, the novel is a love letter to storytelling.

It’s so much more than that, though. Writing the book was a chance for me to rethink what it means to be Latinx and to write fantasy. My lived experience with being Latinx is so complicated, wrought with conflict and misunderstanding, but with this book, I got to imagine something else. A world where secrets can never stay hidden too long. A world where Spanish is a language of poetry and dreams. A world where two young girls can somehow meet across the expanse of an endless desert and become intertwined in each other’s lives.

And above all, I don’t think it’s a universally appealing story. If people who do not relate to it enjoy it…that’s a beautiful thing, and I do hope I’ve written a book that entertains, thrills, and challenges my readers. But it’s also nice to have had the freedom to write something that only a handful of people might truly, truly understand, like there is a hidden emotional language that only some of us speak. It reminds me of those musicians who I found while yearning for a life outside the walls of my home.

If anything, I hope that my work can do the same for someone else out there.

Mark Oshiro is the Hugo-nominated writer of the online Mark Does Stuff universe (Mark Reads and Mark Watches), where they analyze book and TV series. Their novels include Anger Is a Gift, a recipient of the Schneider Family Book Award for 2019, and Each of Us a Desert. Their lifelong goal is to pet every dog in the world.

Don’t forget to check out the other excellent additions in our exclusive Our Books, Our Shelves column with Tor Books!

- A.K. Larkwood & Tamsyn Muir in Conversation, by A.K Larkwood and Tamsyn Muir

- BE A QUITTER, or HOW TO WRITE THE NOVEL OF YOUR HEART, by K.M. Szpara

- Down with Literary Snobbery, Long Live Genre, by Sarah Kozloff

- Bestselling Author John Scalzi Talks the End of Everything with John Scalzi

- A Billion Thoughts at Once by TJ Klune

- RIP, IRL: Fandom Has Always Lived Online by Camilla Bruce and Kit Rocha

- Alaya Dawn Johnson on Writing and Book Advocacy with Alaya Dawn Johnson

- On Persistence, Nearly Giving Up, and Writing On by Martha Wells

- The Piss Problem: The Politics Behind Peeing in Space by Mary Robinette Kowal

- What Can Gender Swapping in Stories Tell Us About Ourselves by Kate Elliot

- An Exclusive First Look Behind The Scenes of Bestselling Author V.E. Scwhab’s New Novel, The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue with V.E. Schwab

- A Celebration Of Chaotic Good with Andrea Hairston, S.L. Huang, S.A. Hunt, and Ryan Van Loa

- Our Books, Our Shelves: Master of Poisons by Andrea Hairston

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com