The Mary Sue Interview: Fairy Tale Expert and The Turnip Princess Translator Maria Tatar

OUAT...

A contemporary of The Grimm Brothers (Jacob Grimm once said of him, “Nowhere in the whole of Germany is anyone collecting [folklore] so accurately, thoroughly and with such a sensitive ear”), Franz Xaver von Schönwerth was a Bavarian historian who dedicated his life to researching and collecting fairy tales from the oral tradition.

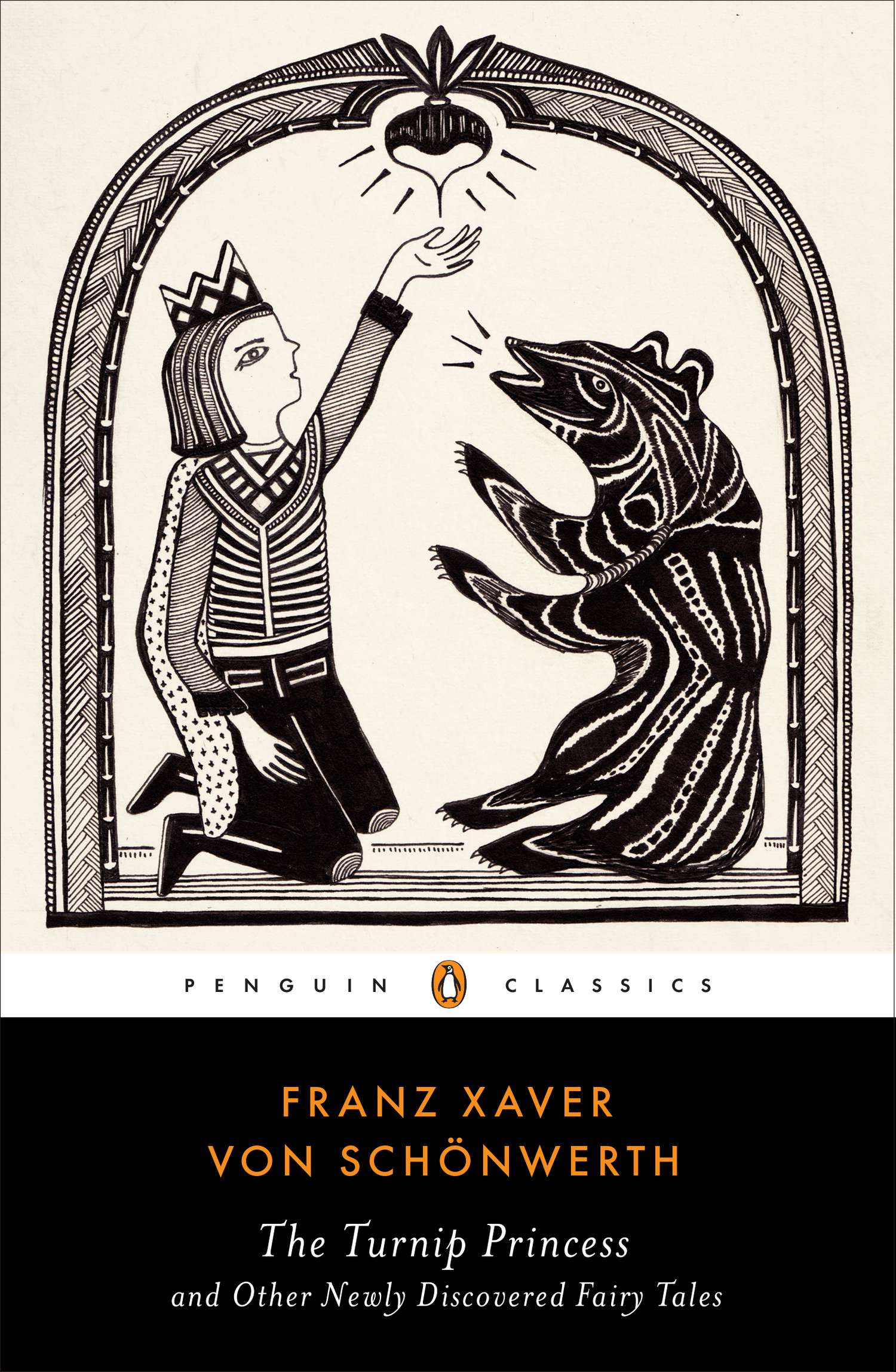

Now, after over 150 years of being “lost” in an archive, Schönwerth’s fairy tales have been translated and curated by folklore expert Maria Tatar into The Turnip Princess and Other Newly Discovered Fairy Tales. Via email, Tatar took the time to talk to us about the enduring appeal of stories like Cinderella, modern oral traditions, and why “the house of fairy tales” has more room for change than we might expect.

Carolyn Cox (TMS): What inspired you to start working with folklore and fairy tales?

Maria Tatar: I’ve always had a deep attachment to stories that are wired for weirdness. I remember clutching Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland tightly to my chest as my 4th-grade teacher scolded me for reading a book that was really meant for adults. When I began reading fairy tales to my children, I was shocked and startled by the grotesque twists and turns in the plots. A stepmother decapitates her stepson and cooks him up in a stew; stepsisters cut off their toes and heels to try to make their feet fit a shoe; a woman wishes desperately for a child and gives birth to a hedgehog. I discovered that these stories were once adult entertainments—what John Updike called the television and pornography of an earlier age. They are melodramatic, operatic, and have a racing energy that helped pass time when told to the rhythms of repetitive labors on long evenings. Today we watch Breaking Bad and read Fifty Shades of Grey—the demands were not all that different in an era before books and electronic entertainments.

TMS: What about the rediscovery of a “lost” fairy tale anthology do you think inspired such excitement, even in people who might not have had a vested interest in mythology or storytelling?

Tatar: Our fairy-tale repertoire is not as expansive as it could be. At times it feels as if we ferociously repeat the same stories: “Cinderella,” “Snow White,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Sleeping Beauty,” and “Jack and the Beanstalk.” Even though we are constantly hitting the refresh button and reinventing the characters and their stories, the appeal of the new is always there. And so we welcome “something completely different”—new stories that might offer other archetypes and tropes. In The Turnip Princess, it’s a delight to discover a boy named Lousehead who slaves away in the kitchen, along with a fellow who is so thrilled to have a pair of red boots that he wears them everywhere—until one gets lost!

TMS: Do you foresee any of Schönwerth’s tales becoming as huge a part of the North American cultural landscape as stories like “Cinderella” or “Snow White,” and if so, which ones?

Tatar: My hope is that Schönwerth’s stories will renew our interest in exploring the many collections found the world over. I imagine that “Prince Goldenlocks” or the “Turnip Princess” will inspire some adventurous spirits to take up their stories and create new versions of them. That’s already happening on the Internet. It’s something of a challenge to unseat the Grimms, who mastered the art of writing down stories taken from an oral tradition. They standardized the stories in ways that made them reader-friendly, without any of the bumps and rough edges you find when you take the story straight from the source. And the Grimms of course also had the advantage of the perfect last name. Schönwerth’s stories have gaps, inconsistencies, and surreal moments that get us thinking more and talking about what the characters could, should, or might do. That’s what I love about them. They are diamonds in the rough, unpolished and at times unfinished, telling us what the stories were like in their oral versions, raw rather than cooked.

TMS: What qualities do you think give certain fairy tales (again, I’m thinking of the immense popularity stories like “Snow White” have in the U.S.) an enduring appeal?

Tatar: Fairy tales are all about the hyper-dysfunctional family: wicked stepmothers, fathers who are bent on marrying their daughters, siblings who viciously gang up on the youngest and weakest, and so on. They are full of excess, exaggeration, and unforgiving violence, enacting worst-case possible scenarios. We have a cultural repetition compulsion about fairy tales precisely because they are so outlandish. As we process what goes on in them, we begin to manage our own anxieties and desires, and we also begin to figure out how to navigate the real world. Fairy

tales, like all great stories, take up cultural conflicts: the predator/prey relationship in “Little Red Riding Hood” (a story that has also come to be about innocence and seduction). In “Beauty and the Beast,” the conflict turns on monstrosity and alterity—how do we react to the other, with revulsion or with kindness and compassion? “Hansel and Gretel”—there’s a coming-of-age story about leaving home, entering the woods, defeating monsters, and finding a way back home.

TMS: I can’t imagine the amount of work that goes into a project like this. Can you talk a little bit about the process of bringing The Turnip Princess together?

Tatar: I initially imagined that I could translate Schönwerth’s stories on the side, but I quickly realized that these tales were completely absorbing and demanded my full attention. First off, they were so different from what the Grimms collected in the 19th century, what Charles Perrault gathered in 17th century-France, and what Giambattista Basile wrote down in 17th-century Italy. There was a rough-hewn quality to them that I wanted to preserve, despite the impulse to imitate the Grimms’ wonderful fairy-tale style. I had different routines, but generally I would read the entire story a couple of times, then take the story one sentence at a time, trying to “English it,” as the philosopher Hannah Arendt put it. Even then each story went through several iterations. I was somewhat daunted by the fact that you can keep making improvements but at a certain point you have to declare victory.

TMS: What’s your favorite story from the collection?

Tatar: Nothing beats “The Enchanted Quill,” with its heroine who claims that she has cooking and cleaning skills so that she can work where the prince lives. She burns all the dishes and fails miserably at keeping house. But she does know how to write, and she uses an enchanted quill to conjure dishes that appear in sparkling bowls and to ward off pesky suitors. She writes her way to a happily ever after.

TMS: Do you think we have any oral traditions today that are comparable to the storytelling seen in Schönwerth’s time?

Tatar: In an earlier age, storytellers were constantly improvising, taking the tropes of fairy tales (princess on a glass mountain, seven-league boots, table that sets itself) and putting them together in new ways. Today fairy tales remain in old media but—short, sweet, and bit-y—they have also migrated into new media, where they are remixed and mashed up to produce new stories, told for us, in the here and now. They operate in kaleidoscopic fashion, constantly adapted to make them culturally relevant. What makes the Schönwerth collection so important is that it reminds us of the vast repertoire out there. Instead of working with a fixed, stable canon of fairy tales, we suddenly discover that animal suitors can come in all shapes, sizes, and species and that the storied Cinderella/Snow White figure—the innocent victim of persecution at home–can also be a boy. The house of fairy tales turns out to be far more capacious than we once imagined.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com