The Other Black Girl Delivers a Humorous but Unflinching Take on the Racist Microaggressions of Publishing

For Black women, tokenism is a very familiar concept. It’s deeply embedded in the fabric of our society and is a multi-layered issue that is rooted in white supremacy. Sometimes it can be subtle, or sometimes it can be blatantly unabashed. But what is most interesting about tokenism is the damage it can do to people of color within their own communities. The nature of tokenism almost demands that we pit ourselves against one another—for the sake of survival in some cases, or esteem in others. But in all cases, it creates irrefutable tension and rifts that can move past the point of healing.

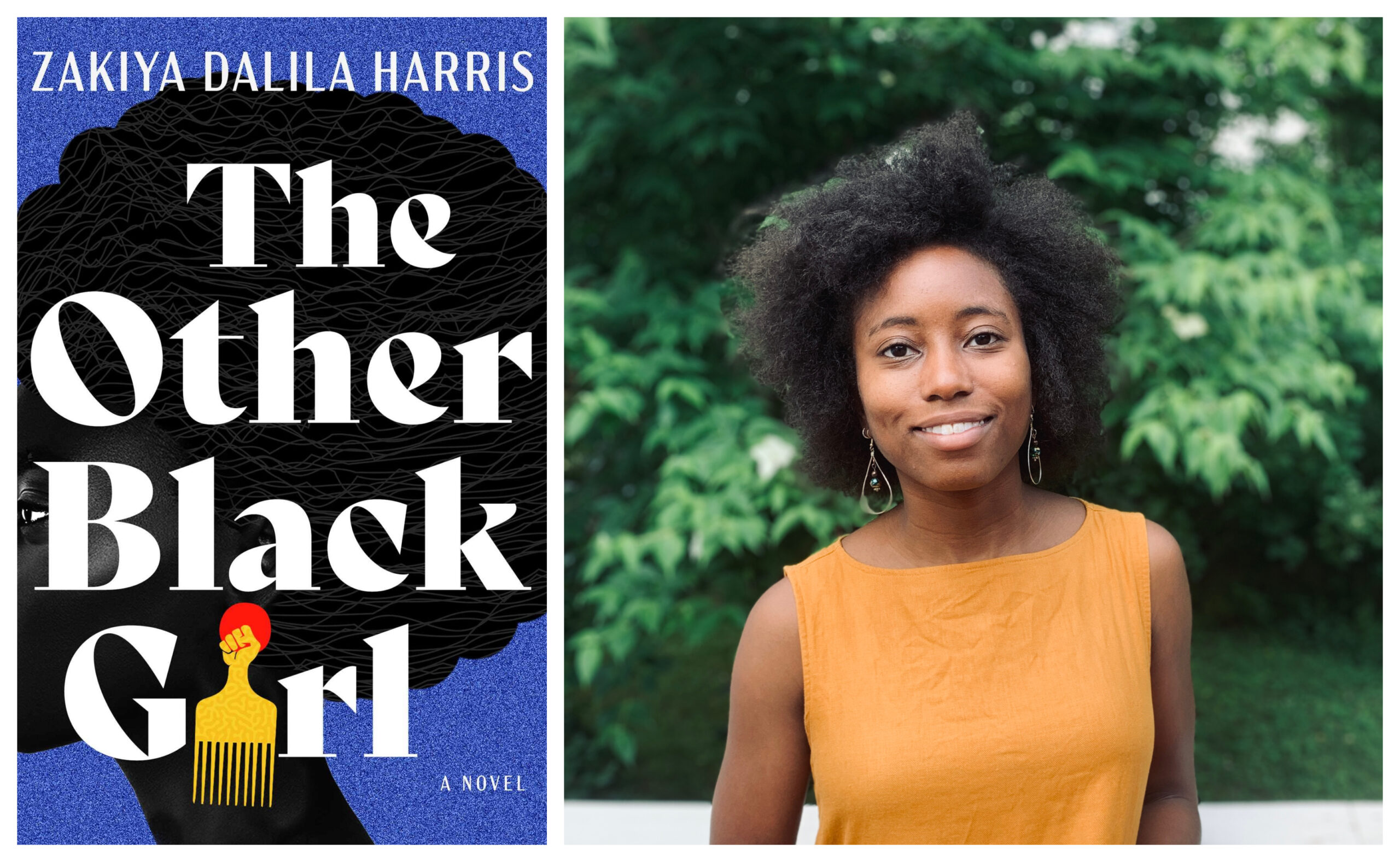

In Zakiya Dalila Harris’s debut, The Other Black Girl, she masterfully speaks to this issue through a clever and satirical lens in the vein of Black Buck and The Devil Wears Prada. When 26 year old Nella Rogers learns that her predominantly white publishing firm is finally hiring another Black woman—a Harlem-bred woman named Hazel—she’s exuberant and thrilled to finally have someone to relate to in the office. But things take a turn when workplace politics elevates Hazel to a status of esteem while Nella is thrown under the bus. And suddenly, tension and unexplainable hostility threatens to not only turn Hazel and Nella against each other, but create chaos more diabolical than the two of them could have ever imagined.

What makes The Other Black Girl so special lies deeper than its strong voice and crisp storytelling; it’s a highly relatable issue that speaks to the broad spectrum of microaggressions and full-on racism that people of color often experience in the workplace. In the best-case scenario, PoC often deal with an unfair level of scrutiny that often makes it impossible for them to navigate their careers in the same way that their white counterparts do. In the worst case, they are dealt the brunt of microaggression and open racism that makes thriving in their jobs almost a futile effort.

For Black women specifically, there is the added layer of misogynoir that forces many to police their behavior to avoid being labelled as “mean” or “difficult to work with,” which makes it interesting (and in some cases, incredibly frustrating) to witness the ways in which Nella and Hazel negotiate themselves through the publishing office. Harris does not frame the characters in a way that forces you to immediately criticize their actions, but she does open up the opportunity for you to examine the different layers of nuance that led each woman to the point that they reach at the apex of the story.

It’s even more interesting that this is all explored through the lens of publishing; it’s no secret that the climate of publishing has historically been unwelcoming to people of color, struggling for many years to reckon with its issues of accessibility, diversity, and subtle racism. To date, there has only been minor progress in the grand scheme of things, and every day there appears to be a new conversation on the hiccups in the industry’s efforts to be inclusive.

Even though this novel is hilarious and full of a tongue-in-cheek tone that flows through each page, the story at the core remains deeply resonant and the pillars of a deeper conversation that remains to be had on the ways in which Black women are unfairly treated, and the ways in which performative diversity can actually lead to an even more exclusive and hostile environment.

(featured image: Atria Books)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com