Toxic Masculinity in Jessica Jones: Kilgrave as a “Nice Guy” and Will Simpson as Misogynistic Hero

Jessica Jones spoilers below!

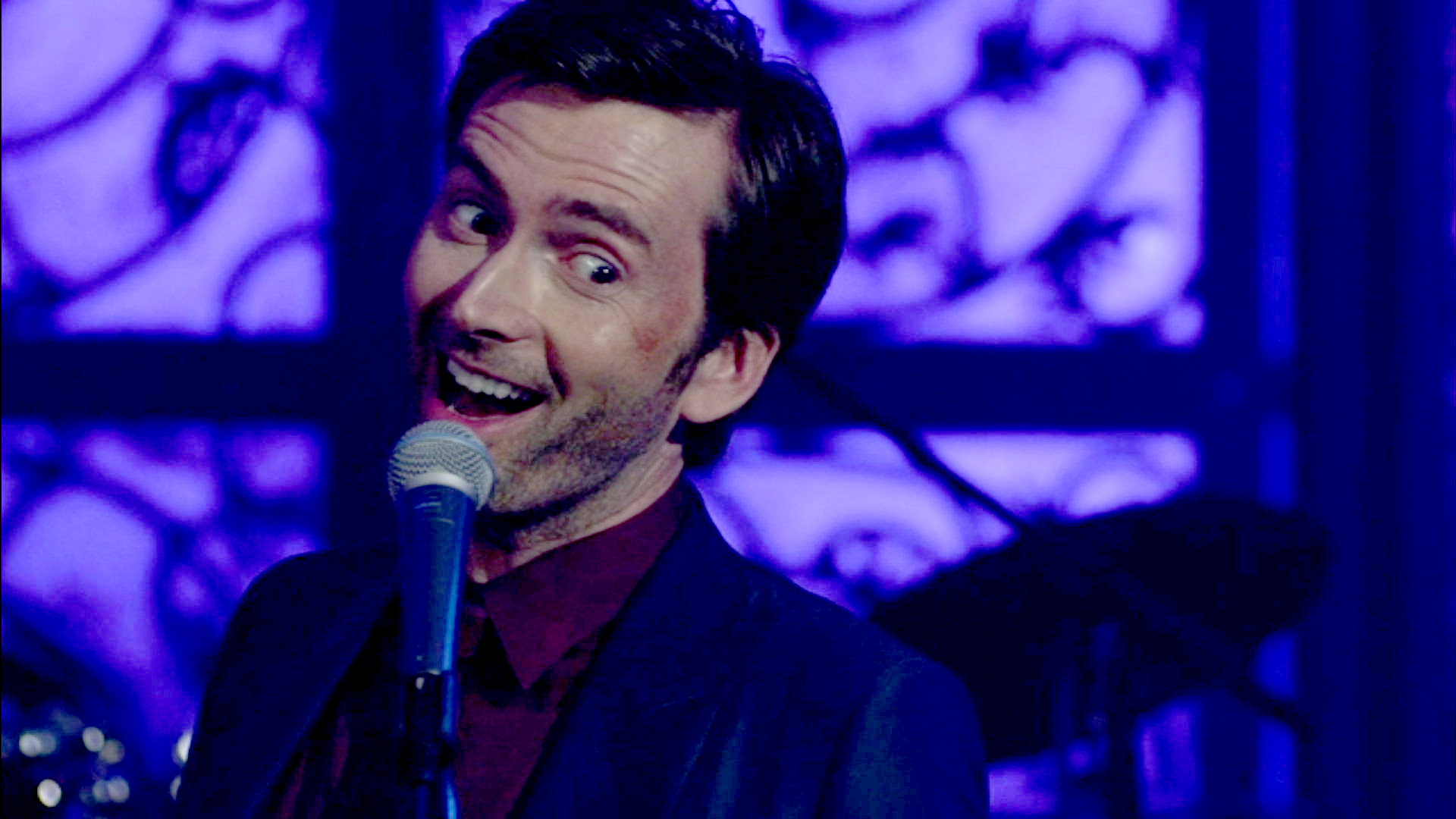

“I’m not torturing you. Why would I? I love you,“ says Jessica Jones villain Kilgrave. From his perspective, it’s clear that he’s a romantic hero. In his world, the effort he put into setting up another meeting with Jessica to declare his love for her—a meeting that only came to pass after stalking, committing murder, and getting an entire station of police officers to aim guns at each other—should be recognized, and Jessica is at fault for not acknowledging how perfect he is for her. He should be applauded for going to the trouble of buying Jessica’s childhood home. The fact that Jessica is attracted to Luke Cage while he’s under Kilgrave’s control but not to Kilgrave himself is clearly an error on her part rather than a well-identified difference in the fact that Cage does an excellent job of respecting her autonomy while Kilgrave is bent on receiving her affection regardless of her feelings and, in its absence, tries to have her killed.

He’s just a nice guy going to great lengths to woo women—right? And it works! Women smile in his presence. He bought Jessica dinner, and she seemed to enjoy having sex with him, so there’s no way he could have raped her. He’s entitled to her, and she is a villain for calling their time together anything less than consensual.

Jessica makes it clear that she wants nothing to do with him. As viewers, we understand this; Kilgrave is explicitly a stalker, an emotional abuser, a murderer, and a rapist. He does a series of things for Jessica that she does not ask for or want, expects access to her in return, becomes violent when she refuses, and sincerely does not understand why he’s in the wrong.

Kilgrave’s entitlement to Jessica is rightfully considered scary, and it mirrors a larger trend of entitlement men feel to women’s affections.

Erin Gloria Ryan defines a Nice Guy as:

“[T]he sort of Guy who has declared himself to be Nice, and thus deserving of positive (usually sexual) attention from the female of his choice, upon whom he has often projected an elaborate fantasy of perfection and willingness that rarely has anything to do with the subject’s actual feelings or desires. When a Nice Guy is romantically rejected by a woman he wants, he lashes out at her, wondering why [she] won’t go out with him. After all, he has been Nice!”

A lot has been said about entitlement at play here—to believe that doing certain actions means you deserve a particular response regardless of other factors is obviously not okay, but it’s a common sentiment expressed by men who want women, and it’s historically been validated by social custom and media. After all, how many men in romantic comedies “fall in love” with women they barely know, do grand romantic gestures that are borderline stalker-y at best, then end up with the object of their affection regardless of some preexisting monogamous relationship she has? While we may balk at the implication that because Jessica does not return Kilgrave’s affections, she deserves to die, there’s a whole Tumblr (content warning) that compiles stories of women violently attacked for saying no.

Officer Will Simpson understands that Kilgrave is dangerous and takes it upon himself to try to protect Trish, the object of his affections, by deciding she should stay behind while he goes off to fight Kilgrave, at one point locking her behind a door to ensure she doesn’t follow. While Trish is willing to state boundaries and call him out when he’s talking over her and Jessica—at one point he argues with them about plans until Trish explicitly says “last night was fun but that doesn’t mean I want your opinion”—she gives his intentions the benefit of the doubt and continues to view him as an asset until it’s become clear he’s been lying, manipulating, and ruining the plans they all agreed on. (There was a pill that amplified these tendencies, of course, but they existed from the start.)

Jessica, on the other hand, does not hide her disdain for the way he interacts with them; when he gives unsolicited advice, she not only calls him out but also makes it clear that she is actually better than he is in the ways he assumes she’s incompetent, referencing her under-4-minute mile and experience with Kilgrave to (rightfully) position herself as the person most qualified to be in charge. On multiple occasions, his continued belief that his opinion is more valuable leads her to leave him talking to no one or shutting a door on his face. Even when he admits he doesn’t know as much, he doesn’t change his behavior, making it hard to blame her. Later, he tells Trish he “doesn’t think [Jessica] likes [him] very much,” and “[Jessica] probably scares guys off.” He never mentions his continued treatment of Jessica’s skills and knowledge as inferior to his own and never seems to consider it may be a factor.

It’s reasonable to guess that Simpson has internalized the narrative of the male hero who protects the more fragile women that dominates media; he tells Trish that, even as a child, many of his roleplay scenarios involved a “male” toy rescuing “female” toys. This impulse toward heroism inspired him to become a police officer to protect “people”—and inspired him to lock Trish in a room so she wouldn’t put herself in danger.

Simpson isn’t a Nice Guy per se, but he’s cut from the same societal cloth as Kilgrave. Where Kilgrave believes he’s entitled to women he’s put on a pedestal and done “favors” for, Simpson believes he’s entitled to the attention of the “fragile” women (Jessica’s superhuman strength notwithstanding) who must be protected. Where Kilgrave uses mind control to force women to give him what he wants, Simpson manipulates situations “for their protection” while undermining their autonomy. They aren’t enacting the precise same version of toxic masculinity, but in both cases, it’s a mixture of entitlement and manipulation that necessitates they view women’s skills, knowledge, and desires as inferior to their own. Perhaps the scariest part of the whole thing is that they’re convinced they’re justified in doing so.

Edeline Wrigh is a writer, artist, and game developer who informally researches the impact of stories and creativity on people and cultures. That’s what she claims, anyway, though she actually spends a lot of time devising new ways to claim playing video games is “productive,” pining over kittens, and dressing like a fairy and dancing with hula hoops. Art, writing, and other chaos can be found via her blog.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com