What Was the First Anime?

Also: Osamu Tezuka was a badass

Throughout the last century, anime has grown from a single artists filming works with chalk boards to a multi-million dollar international mega-industry — though similar things could be said about the film industry in general. While in Japan “anime” is simply a shortening of “animation,” just about everywhere else, the word has come to mean animation specifically from Japan. What are the genre’s origins? If we’re thinking specifically about the TV shows we all know and love today, spanning back decades, is there a clear “first anime?” Is there a surprisingly awesome pro-labor hero at the core of this story? The answer to those last two questions is “yes.”

But first, let’s work up to the first tried-and-true TV anime, because I’m a geek and think animation history is interesting and fun. The first animated works from Japan occurred around 1916 and 1917 at the hands of the “fathers of anime”: manga artists Oten Shimokawa and Junichi Kouchi, and painter Seitaro Kitayama. (I’m getting a lot of this information from RightStuf Anime — their story is much longer and goes into more detail, if you’re interested.) Shimokawa is credited with creating the first Japanese animated film. These films were about five minutes long and were animated by drawing, erasing, and re-drawing images with chalk on a chalkboard. Like all early films, they relied on a theater’s in-house musicians and performers to provide audio. Sadly, most of these early works were lost to history. Tragic earthquakes, world wars, highly flammable film — name your catastrophe of choice.

The 1930s saw the first short animated films with pre-recorded voices and cel animation, respectively. The former first, 1933’s Within The World and Power of Women, is a wildly sexist story about a guy who gets tired of his “domineering wife” and so has an affair with his secretary. 1934’s Chagama Ondo, on the other hand, is a delightful tale of a group of trouble-making shape-shifting tanuki stealing a Buddhist monk’s gramophone so that they can dance to jams all day. It also features a scary knife-wielding old lady who looks a lot like Moe from The Simpsons. (Cel animation, by the way, would remain the worldwide norm until the digital era. Cel animation requires layering paintings on a translucent cel on top of one another, taking a picture, and then shifting and changing the elements. Wild stuff.)

The first full-length Japanese animated film, Momotaro: Umi no Shinpei, was released in 1945. The English translation is Momotaro: Sacred Sailors, because “shinpei” in this context means “soldier dispatched by a god.” If that word strikes you as a lot and inspires some timeline calculus in your head, that’s no coincidence: Momotaro was, indeed, a World War 2 propaganda film commissioned by the Japanese navy. Unlike the washes of highly problematic Donald Duck cartoons Disney would like us to forget, animation wasn’t used for wartime propaganda as widely in Japan as it was in the States. Momotaro was therefore Propaganda For Kids. However, Mitsuyo Seo, the director, did at least imbue the film with a hope for peace. And that, in turn, inspired our story’s hero: Osamu Tezuka.

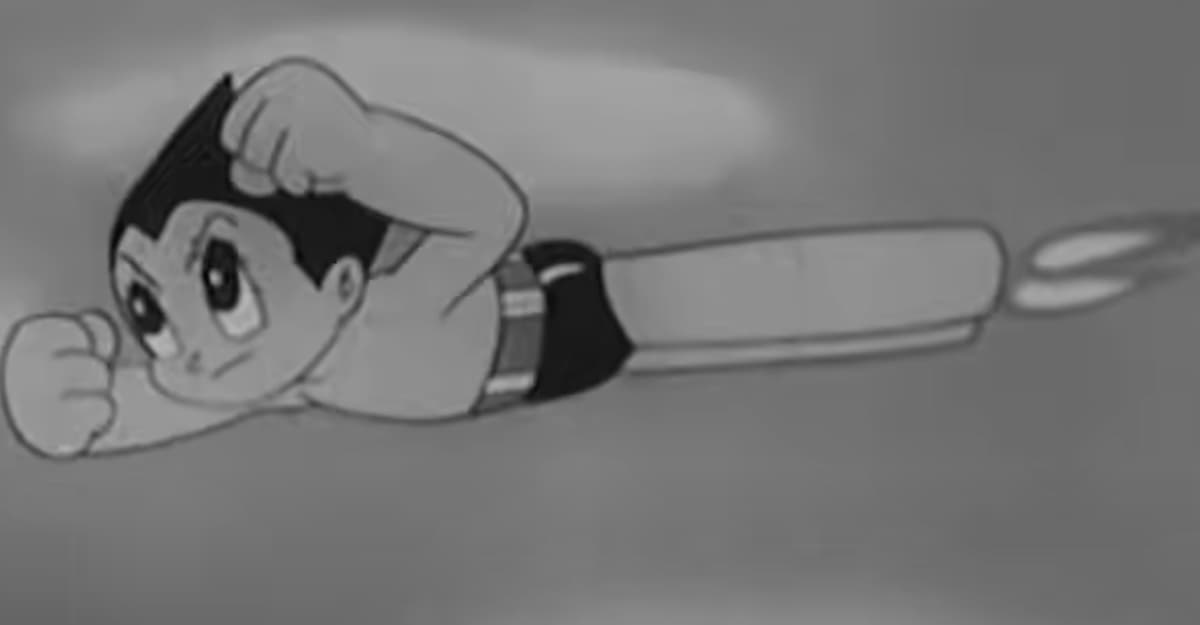

When television started coming to Japan in 1958, there were a few animated programs that ran episodes ranging from three to ten minutes, the first of which was Mole’s Adventure. But, largely, most of the cartoons airing on Japanese TV were international imports. In other words, Japanese audiences and American audiences alike were watching The Flintstones. Tezuka thought this was lame and wanted Japanese audiences to have an original Japanese show. Tezuka by this time was a well-established mangaka who had worked with now-Toei Animation to produce several film adaptations of his work. He used his influence, his cost-cutting cunning, and his studio Mushi Pro to make the first 25-minute Japanese animated TV show: Tetsuwan Atomu, AKA Astro Boy, which premiered in 1963.

Related: Who Created Anime? on Twinfinite

Astro Boy likely sounds familiar to you. Even if, like me, you have a bad habit of conflating Astro Boy and Mega Man. Like the manga it was based on, the show was a huge hit: 40% of Japanese households with a TV watched Tetsuwan Atomu. That level of success earned the show syndication and translation into other countries, with 104 of the 193 episodes getting translated into English and airing on NBC in the US. It became one of those quintessential legacy cartoons whose existence you were aware of, even if you didn’t know what it was about.

So let me take this moment to tell you what Tetsuwan Atomu was about, because I’m shook. The short of it: a well-renowned scientist’s son is killed in a car crash, so he builds a “super robot” in his likeness. However, he’s angry that his robot son won’t grow up like this real son, so he sells Astro / Atom to the circus, where he’s forced to compete in, essentially, gladiator tournaments. Eventually, Astro / Atom meets a new, nicer scientist friend who took his shitty dad’s job, and he frees him from this circus of hell. RIGHT?! So, anyway, Astro / Atom is a huge pacifist.

Tetsuwan Atomu‘s laid the groundwork for a ton of shows to follow it immediately. NBC even helped Mushi Pro get together a coloring department so they could make another wildly popular series, Kimba the White Lion, in 1965 (you know, the series The Lion King supposedly ripped off). Tetsuwan Atomu‘s legacy also includes establishing a ton of anime tropes that are still in practice today. Perhaps the most notable is the long, catchy theme song, which was one way Tezuka cut per-episode labor and costs. However, the characters’ big eyes and absurd hairstyles would remain a prominent style choice for decades to come.

Now, here’s where I went into my research hole where I realized Osamu Tezuka freaking rules. Please indulge me in this. Apparently, during his time at Toei, Tezuka was actively pushing for unionization. That, in conjunction with his annoyance over Toei’s control over his productions, influenced Tezuka to let his contract lapse and form his own studio. He took a ton of Toei’s best animators with him, because he used his manga royalties to offer everyone a significantly higher wage. Mind you, the studio hadn’t made anything yet, so these wages were, indeed, coming directly from Tezuka’s pocket. One animator, whose wages were ¥8,000 at Toei, recalled that Tezuka asked him how much he wanted at Mushi Pro. When the animator hesitated to answer, Tezuka offered him ¥21,000. As if that wasn’t badass enough, Tezuka’s list of poached animators included Kazuko Nakamura, the first (recorded) female animator in Japan. Nakamura would remain one of Tezuka’s go-to animators, even after Mushi Pro disbanded. At Mushi Pro, she became the first female animation director for every episode on an entire series, Knight of the Ribbon (a shoujo).

So, that’s the incredibly long answer to how Tetsuwan Atomu / Astro Boy became the first syndicated 25-minute TV anime. Tezuka eventually decided to make racy adult anime films, which became known as the Animerama trilogy. Of course, anime history continues from there, with tales of how anime continued on the path of world domination. I, personally, like to cite Akira in that particular story. But that’s a tale for another day.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com