What’s In Your Literary Canon?

When I was finishing up grad school and deciding if I wanted to get my Ph.D. after my Master’s degree, I looked up the list of books that it is recommended you read before taking the GRE Literature Test and I remember just sighing. There was so much there that I just was not interested in visiting or revisiting, even though I was familiar with a lot of it. Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not anti-dead white dude books, most of my favorite books are just that, but it doesn’t mean that I am intellectually stimulated by most of them.

In Lindsay Ellis’ latest video for PBS, she explains how the literary canon is really based on the opinions of old white male academics with input from young white male academics.

The literary canon is elitist towards everyone and even though some on the alt-right have this wide-eyed fetishization for this concept called “The West” (thank you ContraPoints), it does not mean that Western canon is inclusive of everyone. Nor does including new voices into canon mean that they are now perfect. Expanding literary canon is a means of saying that we are having conversations with other stories and other authors now, and that’s okay. Hell, sometimes we can be having new conversations with old authors who we didn’t know about, but found later in life. Books should not be a one-size-fits-all experience of literary value.

If I could add some texts into the “official” Western literary canon these would be my five additions. Spoiler, an old white man book is on the list.

5) The fair triumvirate of wit —Eliza Haywood, Delarivier Manley and Aphra Behn:

The novel is popular because of women. I spoke about this collection of ladies when I talked about amatory fiction and Fantomina, but let it be known once more that from 1660-1730, female writers were killing it and before there was the novel, it was amatory fiction that was selling like crazy and creating a place to make money selling these stories.

Eliza Haywood is one of the founders of the novel, in addition to writing and publishing over seventy works during her lifetime. She was known for being transgressive and outspoken in her time, and no one really knows any truths about her except the day she died and what she wrote. Gangster.

Delarivier Manley was one of the first well-known female political satirists. She was so hardcore, she was arrested for her writing and was almost sued for libel because her work discredited “half the arena of ruling Whig politicians, as well as moderate Tories.” She collaborated with Jonathan Swift, who enjoyed her work even though he thought it “missed the mark” at times. Considering that Swift actually knew what satire was, that is a sign of how good she was when she did hit the mark.

Aphra Behn (who wrote as Astraea) was one of the first women to earn a living being a writer (and got called a whore because of it) and many women authors decided her work was “unfit” because it was “lewd” “corrupt” and “deplorable.” Yet in the modern era with people like Virginia Woolf, Behn is slowly (very slowly) getting her due. As Woolf wrote, in A Room of One’s Own:

“All women together, ought to let flowers fall upon the grave of Aphra Behn… for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds… Behn proved that money could be made by writing at the sacrifice, perhaps, of certain agreeable qualities; and so by degrees writing became not merely a sign of folly and a distracted mind but was of practical importance.”

4) Clarissa by Samuel Richardson:

I would never recommend Clarissa if you don’t love melodrama and reading literally tomes because at over 1000 pages unabridged, Clarissa is one of the longest books in the English language. There are abridged versions, but I’ve not checked them out myself. It tells the story of the beautiful and virtuous Clarissa Harlowe, whose new money family is insecure and petty, due to their new position in life. They plan to concentrate all of their wealth and power into their son James, but when Clarissa’s grandfather leaves her a substantial piece of property upon his death, the family ends up tearing their daughter apart in order to keep control over her. The book also had the proto-Byronic rake character of Robert Lovelace, who lusts after Clarissa and uses dubious means to “claim” her.

Harold Bloom called Clarissa, “one of the most central and influential novels in the English literary tradition”, yet it is mostly unknown unless you take an 18th century lit class or get into the period yourself. Despite that ringing endorsement from the king of Western Canon, Richardson’s work has mostly fallen aside and his rival, Henry Fielding of Tom Joness fame, has become the one England’s best-known satirists. Stupid satirists and their Scriblerus Club.

3) Clotel by Williams Wells Brown:

Another book I found out about while in my Master’s program is the anti-slavery narrative Clotel by Williams Wells Brown. Brown, the son of a slave and a slave owner, escaped slavery and became an anti-slavery writer and lecturer, who supported, in addition to the abolishment of slavery: temperance, women’s suffrage, pacifism, prison reform, and the current anti-tobacco movement. When he moved to London he wrote his novel Clotel, which is considered to be the first novel published by an African-American.

The novel explores the destructive nature of slavery on the black family and especially black women. The framing of the narrative was based around the character of Clotel, a mixed-race woman who was the daughter of a mixed-race slave name Currer and Thomas Jefferson. Yes, that Thomas Jefferson. At the time the relationship between Jefferson and Sally Hemmings was just a rumor (later confirmed by science).

Through the novel, Brown explores the cruelty of slavery, the sexual and emotional abuse that black women suffer as a result and how slavery is incompatible with American’s values and identity as a country. Much like Richardson, he was also overshadowed by his rival, Fredrick Douglass and the two feuded openly because Brown tended to come in second place.

It was very Salieri and Mozart as told by Amadeus.

Still, Clotel is an excellent examination, and brief, novel about the emotional scars of slavery on the black woman, her children, and the black family as a whole.

2) Beloved by Toni Morrison:

Toni Morrison is America’s greatest living author and we should all be grateful. Her 1987 novel, Beloved tells the story of Sethe, a former slave, who lives in Cincinnati, Ohio living with the trauma of slavery and the death of her daughter by her own hand. Inspired by the true story of Margaret Garner, a slave woman who killing her own daughter rather than allowing her child to reenslaved. Beloved is no doubt a classic and a book that we are asked to read in some stage of school, but what makes it such an obvious addition to canon is something that Harold Bloom says.

He says that canon is made up of authors having conversations with certain texts throughout time. Well, authors and readers are having conversations with Beloved. Most notably and even in a different genre, is N.K. Jemisin’s The Broken Earth trilogy, which is also inspired by Garner’s story. For black authors ever since Beloved, this text has been something that we go back as a way of examining the effects of trauma, not just on the body, but on the soul.

1) The Women of Letters:

There are a lot of female authors we will never know about because instead of writing novels or poems or plays, they wrote letters. You may ask “but Princess, letters are not real authorship are they?”

Well, tell that to William Wordsworth who took his sister’s letters (Dorothy Wordsworth) and use them to craft his own, now, legendary works of poetry relying on her descriptions.

Or Zelda Fitzgerland whose creativity and diary entries were milked so that her hack husband could have inspiration (I apologize to the F. Scott fans in the audience).

Or Anne Lister whose diaries not only contain some of the most extensive information about the social, political and economic events of the time; the four-million-word diary also has very intimate details of her lesbian relationships in 19th century England.

The scope of women’s literary value to literature has been deeply under-examined, even with the work of feminist criticism. We owe it to ourselves to expand the canon to all the works that tell us more about the things we didn’t know, then just share the same stories for all time.

What would be in your literary canon?

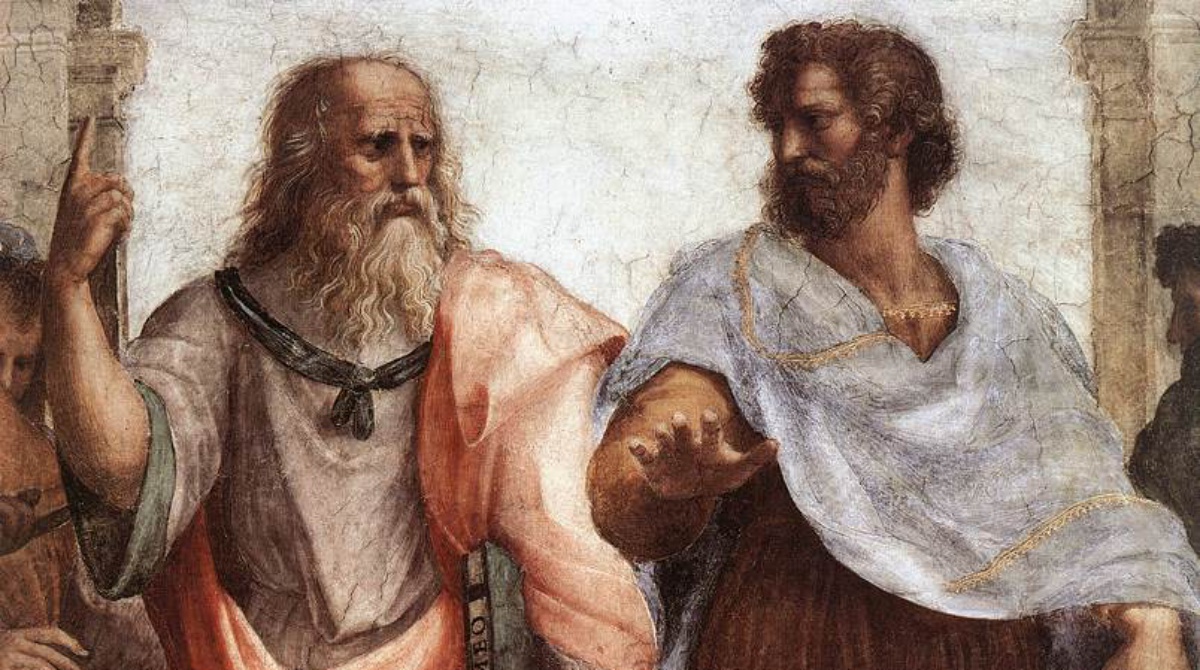

(image: Public Domain/ a detail of The School of Athens, a fresco by Raphael)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com