Why Must Women Fall in Love to Be Human?

Robot women are made—literally—to love. The notion of “robot women” is an odd concept at first glance, considering robots and artificial intelligences don’t have to have a gender, or even a biological sex. Their minds and bodies can conceivably have any shape, or even no shape at all—think Cortana, an AI from the Halo games. There’s no real reason she has to be shaped like a human woman; she could be genderless, or a sphere, or a penguin.

A writer makes a choice when they gender a robot, whether they realize it or not, and what we typically see is hard-coded gender essentialism that boils down to this: if the robot has boobs, it’s a woman; if not, it’s a man. Robot women mimic human female biology, as far back as Rosey from The Jetsons or the automaton in Metropolis. Meanwhile, robot men are free to take on whatever shape the job needs. C-3P0’s body is humanoid but sexless, and R2-D2 looks more like a trash can than a human of any gender, but in the Star Wars universe, both use he/him pronouns and are considered male characters.

This can be blamed on sexbots, a whole subgenre of robot women designed solely to be sexual objects for the pleasure of men. Sexbots abound in early science fiction, as in the original Westworld and The Stepford Wives movies, and now come in holographic form like Joi from Blade Runner 2049 or Krieger’s virtual girlfriend, Mitsuko, on Archer. You might, rarely, see a male sexbot, as in the novel The Silver Metal Lover by Tanith Lee.

As technology advances, some sexbots are made to be more than sexbots, providing not only sex but companionship and even that most human of emotions: love. Sometimes, that love transforms the robot from a collection of wires and electrical signals to a feeling, thinking person. Just as a writer chooses to gender a robot, they also make a choice in the stories they write for their characters, so when a particular kind of story is chosen often enough to become a trope, like the robot woman who proves her humanity by falling in love, it’s worth investigating why that story is popular and what the real-world implications of the story might be.

It’s easy to see why this trope is appealing. Humans want to believe that something as wonderful as love is the center of what it means to be human, and as evidenced by the success of HBO’s Westworld, achieving personhood is one of the most fascinating stories you can tell about a robot. Not all stories about robots becoming “real” people focus on romantic love; both the short-lived TV show Extant and the blockbuster film A.I.: Artificial Intelligence feature young boy robots who want a family to love, and Westworld’s Maeve becomes fully realized through her love for her daughter.

But it’s clear that we humans consider the capability for romantic love a core feature of personhood. The Cylons from the more recent Battlestar Galactica series believe they cannot reproduce—they can’t create new people—unless they are in love. Even when it’s not the center of the story, the ability to love (or lack thereof) is shorthand to signal a robot’s humanity. It’s why we see Wall-E longingly watching a romance in the first scene of his movie, and why glitchy robots crying, “Love? Does not compute!” are a go-to joke in science fiction.

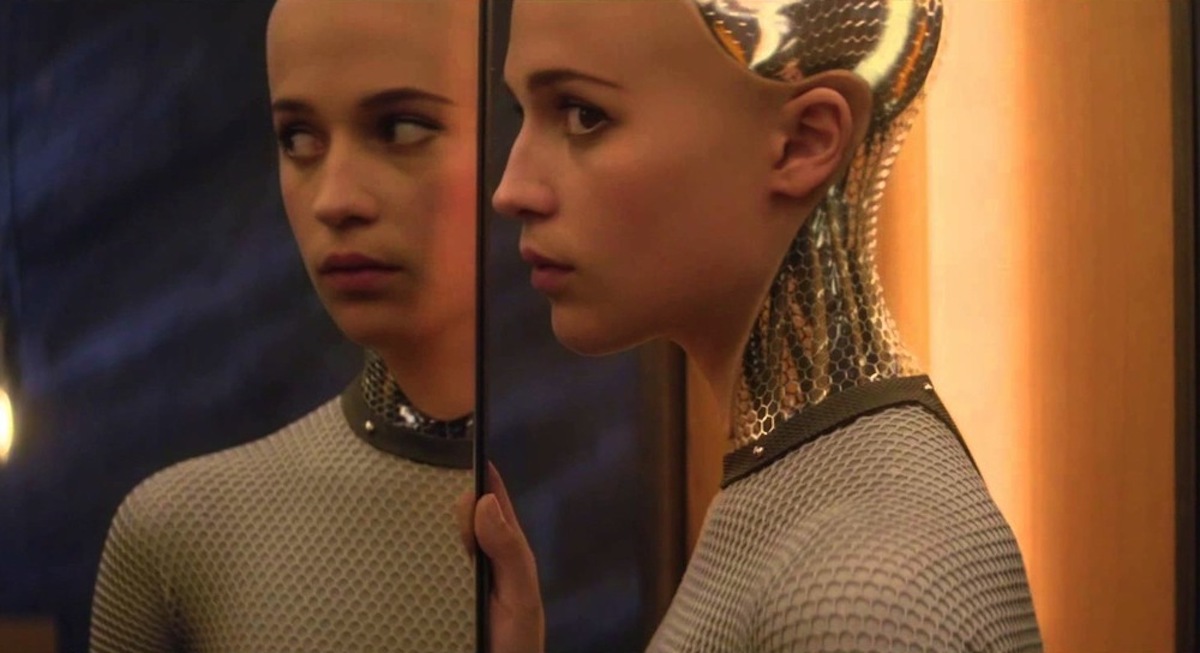

The problem with the trope is that the ability to fall in love with the male protagonist—or at least be the believable object of his love—is the test of a robot woman’s personhood. Her humanity revolves around whether she can convince a man that she loves him, rather than her philosophical insight or artistic skill or exquisite knock-knock jokes. Ex Machina makes this test literal, with a twist: Ava’s Turing Test is whether she can make Caleb fall in love with her. The test isn’t always explicit, but we often see men convinced of a robot woman’s sentience solely because he believes she loves him, or he loves her.

Deckard’s relationship with Rachel in the original Blade Runner shows the audience (if not Deckard himself) that the replicants are people, too. In Her, Theodore defends his AI girlfriend Samantha against claims she can’t truly feel emotion. Even Pixel Perfect, a Disney movie, features a scene in which Roscoe defends his feelings for Loretta, his holographic pop star creation, on the basis that she’s just as real as anyone else. Most of the sympathetic Cylons in Battlestar Galactica are women who fall in love with human men. This trope is so pervasive that it’s hard to think of a single robot or AI woman whose story doesn’t revolve around romantic love or personhood. GLaDOS from Portal and J9 from My Life as a Teenage Robot are the only examples that come to mind.

Robot men, on the other hand, rarely have their personhood or sentience questioned. The Terminator doesn’t have to show his emotional depth by falling in love with Sarah Connor. He’s a killing machine, he’s cool, and that’s all the writers and the audience care about. But for Cameron, a T-900 Terminator played by Summer Glau on The Sarah Connor Chronicles, identity and personhood are central questions to her story, and those questions are entangled with her romantic relationship with John Connor.

Regardless of whether a robot man is on equal footing with “real” humans in a story, his personhood isn’t usually at stake. We can see that robots like Bender from Futurama, C-3P0, R2, and Marvin from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy are intelligent, emotional creatures through their cheeky bickering. They don’t have to prove it through a psychodrama built around whether they can fall in love. Even when there is some question about a robot man’s humanity, it isn’t usually resolved by falling in love. Star Trek’s Data is very concerned with the nature of humanity and even has a brief romance, but he spends most of his onscreen time pondering art, philosophy, emotions, and what they mean to humans. Even Johnny 5 in Short Circuit proves he’s alive by … laughing. That’s it.

So why do robot women have to fall in love to prove their sentience, their worthiness, their personhood in story after story? Well, let’s look at what happens when a woman robot fails the test, when she doesn’t love a man the way he wants her to.

In Her, once Theodore learns that Samantha is romantically interested in (several thousand) other people, Samantha and all other AI ascend to another form of being. She changes from human-enough-to-love to something inhuman and incomprehensible to him. Blade Runner 2049 gives us K, a replicant who begins to believe that both he and Joi, his AI companion, could possibly have real, human feelings, and that the one bright distraction in his life might be able to love him. Joi is the one to suggest that K might be human after all, and she convinces him to give himself a real name: Joe. In nearly the final scene, after his Joi has been destroyed, K/Joe interacts with a Joi advertisement that refers to every man as Joe and realizes his Joi never loved him, and so was never a person. In Ex Machina, when Ava has finally convinced Caleb of her personhood, he helps her escape, and she reveals she was manipulating him the whole time. She kills her creator, repairs her broken body with bits from other robots—a vivid Frankenstein’s monster allusion—then leaves Caleb to die.

This trope, repeated across generations of science fiction, sends a clear message to the viewer: Women who don’t love men are inhuman, incomprehensible, or monstrous. In a way, this is just one example of a bigger phenomenon in media, where the only women in a story are girlfriends and wives, but it’s especially insidious to perpetually question the personhood of female characters and tie that personhood to their ability to love. The writers and creators of these stories are, largely, men. The protagonists, who we as the audience are supposed to empathize with, are, largely, men. And these stories say that women who don’t love you, the male protagonist, or who fall out of love with you or don’t love you in exactly the right way, are not real, human people—they’re nothing but empty sexbots.

Lisa is a D.C.-area native who loves words. She reads them, writes them, and studies how the brain understands them. She’d eat them if she could. Her areas of geekdom expertise are feminist and eco-topian science fiction, language and cognition, and aliens with weird-as-heck biologies.

(image: A24)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com