Busting the Binary Stereotype: Women Warriors, Weaklings, and Healers

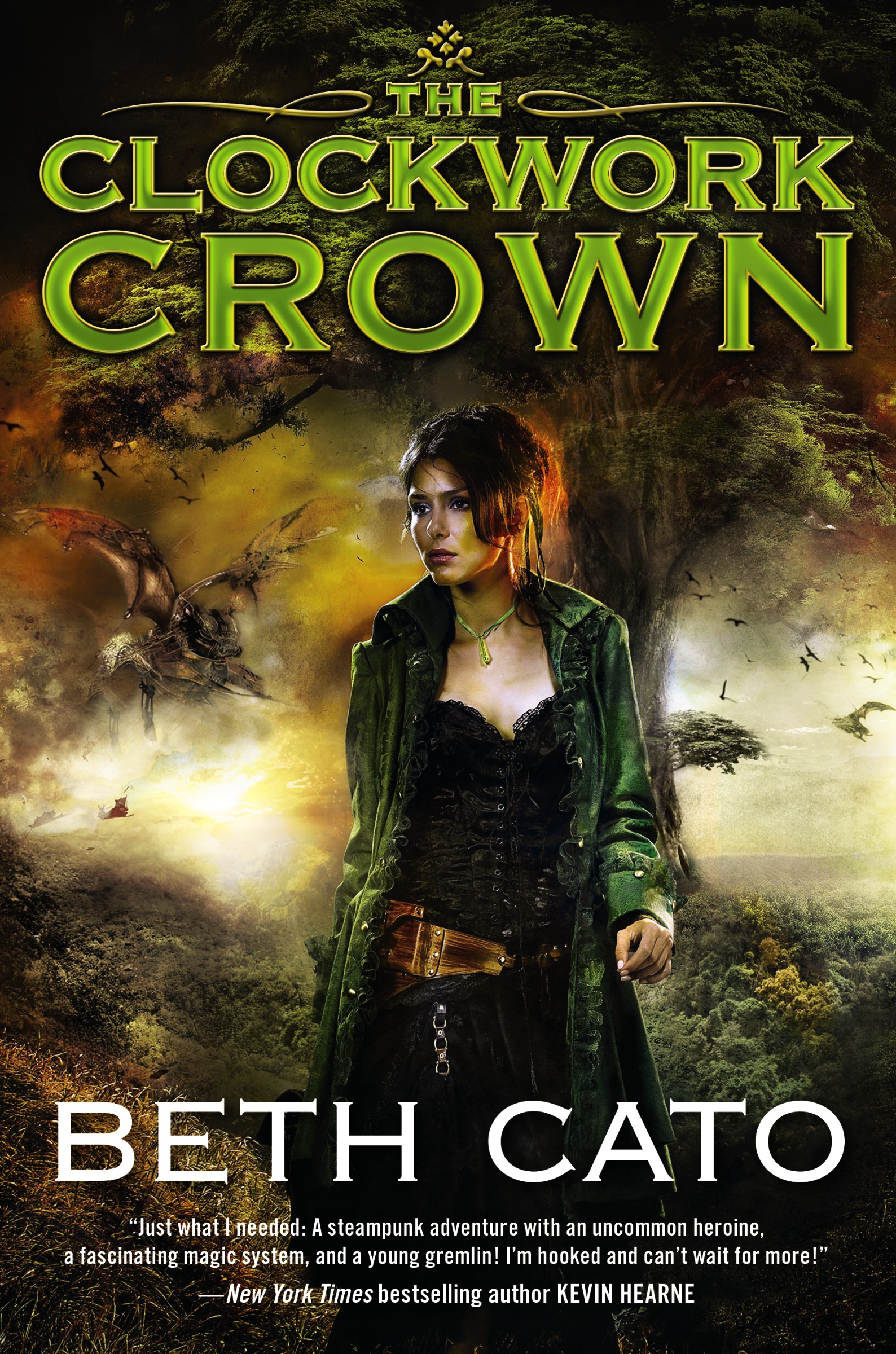

With The Clockwork Crown, out tomorrow, Beth Cato delivers an action-packed, magic-filled sequel to her debut fantasy novel. Octavia Leander is a powerful magical healer who has just narrowly avoided assassination and is on the run with handsome ex-Clockwork Dagger Alonzo Garrett. They travel across Caskentia searching for safety, and for answers – how is Octavia so powerful, and why does it look like she’s undergoing a transformation unlike any seen for hundreds of years? Joined by unlikely allies, Octavia must get to the source of her power, the Lady’s Tree, before a brewing civil war disrupts her entire world.

Cato joins us on The Mary Sue to share her experience writing women in fantasy.

I remember playing Advanced Dungeons & Dragons with friends when I was about fifteen. My character was a cleric, as usual for me. As we wandered through a maze, the dungeon master described a noise like an animal cry coming from a branched tunnel. I wanted to investigate in case someone needed help but in the two seconds that I dallied, some monster lurched out and ate me.

I was indignant.

“You’re a cleric,” my sadistic dungeon master jeered. “You’re weak. You don’t have the hit points to withstand a paper cut.”

And that pissed me off–because he was right. Healers in every table-top game, video game, or book were supporting characters designed to be physically weak with low hit points. Their equipment was built for fan-service, not defense, and their compassion wasn’t an asset, but a vulnerability. The healer was utterly reliant on the (almost always) male hero.

Always the sidekick, never the ass-kicker.

Final Fantasy II for Super Nintendo instigated my healer obsession when I was almost twelve years old. My grandpa had suffered from prolonged illness and passed away just months before. Even though my family had years to accept that inevitable end, his loss sent us reeling. We all coped in different ways. For me, it meant a descent into a 16-bit world with a Nobuo Uematsu soundtrack.

My fixation centered on the character of Rosa; she was smart, beautiful, and the most powerful white wizard in the game. As my love for her grew, so did my annoyance at how healers were taken for granted and generally dissed.

I realized that across books and games far too many women fell into binary stereotypes: warrior or weakling. They were either a tough gal with chainmail and a sword, or the princess in need of rescuing. The powerful magic of role-playing game healers was counterbalanced by physical weakness and complete uselessness when they weren’t casting Cure. (Offensive magic users were similarly weakened, but at least they had the ability to blow things up in spectacular fashion.)

Epic fantasy novels in particular liked to show women as priestesses or witches who could heal. Because, you know, women are kind and nurturing like that (and men with that kind of compassion are also often dismissed as being “feminine” or otherwise feeble). Plus, the hero needs a pretty and kind girl to save in the course of the plot, right? Even my beloved Final Fantasy II used that plot device. Sigh.

I wanted middle ground. I wanted realism. Not for the healer to be made into a demigod, but to have her magic balanced in ways that still allowed her to be, well, competent on her own.

After twenty years of waiting and searching for a strong healer heroine, I decided I should write her myself. The Clockwork Dagger started with the idea of a steampunk version of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, with my healer heroine as the murder target.

Octavia Leander is a young woman with ten years of experience working the medical wards on the front-line of war. Her physical strength is more noteworthy than her appearance. She’s a farm girl who can carry a newborn calf or haul a comatose body. Her compassion sometimes verges on the edge of foolishness, but she knows her limits. She doesn’t have a death wish. On the contrary, she would save everyone if she could. She’s the kind of person who will fire a gun in self-defense and then rush to save her enemy’s life.

I wanted her desire to help and heal to be genuine. Compassion cannot and should not be equated with being passive or pacifist, or in more blunt terms, a weakling or coward.

Look at real battlefield medics throughout history and into present day. Read a memoir like Ellen N. La Motte’s The Backwash of War. Her descriptions of wards in World War I France were so visceral and abhorrent that the United States forced the book out of print because it was bad for wartime morale. Don’t tell me that a woman who volunteers for such duty is weak, mentally or physically. Don’t tell me that she’s not a warrior when she’s face to face with Death every single day on a sordid repeat cycle, when she can’t wash the stench of gangrene from her clothes, when she’s the one dragging corpses out to a pit because all the men are too busy dying in their cots or in the trenches.

Don’t tell me that woman isn’t capable of saving the world. She is. One person at a time.

These days we talk a lot about role-models in genre fiction. It’s vital that we see people like ourselves who are capable of good and powerful deeds, especially when we’re young and brittle in the grip of reality. That’s why it means the most to me when I hear from girls who are eleven, twelve, or thirteen who read and loved my first novel. I know how much I craved a book like this at that age and could never find it. I remember how the very idea of healers first sparked something deep inside me.

That’s why it’s even more important that we bust the binary warrior/weakling stereotype and show that the truth is at neither extreme.

Warrior women can tote swords or pilot starships, yes, but they can also be healers in starched-white medical uniforms. They can be kind without being weak. They can be captured by the enemy, but they’ll also save themselves, thank you very much. And you better believe they can handle a lot worse than a mere paper cut.

The Clockwork Crown is available tomorrow, June 9th, from Harper Voyager.

Beth Cato resides in the outskirts of Phoenix, AZ. Her husband Jason, son Nicholas, and crazy cat keep her busy, but she still manages to squeeze in time for writing and other activities that help preserve her sanity. She is originally from Hanford, CA, a lovely city often pungent with cow manure.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com