Three Billboards’ Golden Globe Is a Win for Survivors, But With a Price We Shouldn’t Have to Pay

**Spoilers for Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri below.**

This weekend, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri took home the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture – Drama. I’m not the biggest fan of award shows, but this particular win struck a chord with me both as a survivor of sexual violence and as an activist.

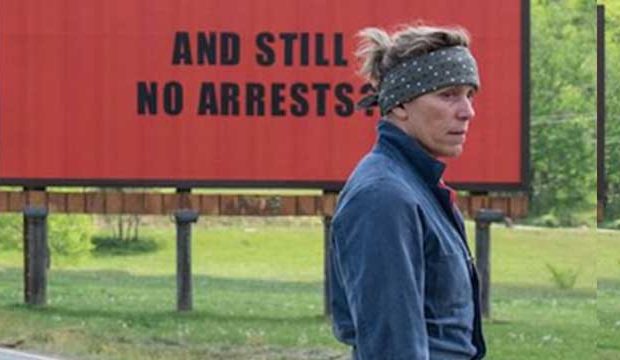

Three Billboards tells the story of Mildred Hayes’ (Frances McDormand) public callout of her local police department with three billboards that read “Raped while dying. And still no arrests? How come, Chief Willoughby?” on a backroad in Ebbing, seven months after her daughter, Angela, was murdered.

The film unapologetically critiques the way our society and justice system handle sexual violence. There is constant pressure for Hayes to stay silent, though her daughter’s killer is still out there. In one scene, her son, Robbie, argues with Hayes over the billboards, saying he’s embarrassed to go to school. In his argument, Robbie unveils the privilege people who have not experienced sexual violence live with every day: the knowledge that Angela was not only murdered, but raped, made him uncomfortable, and he’d prefer to ignore it because that’s most convenient for him. Hayes is a survivor of domestic violence, so her son’s discomfort doesn’t phase her, a conclusion to the exchange that is all too satisfying, though heartbreaking nonetheless.

Throughout the film, we learn that Willoughby—who’s dying of pancreatic cancer—actually is on Hayes’ side. We learn of the extra steps he’s taken to try to track down Angela’s murderer, and that he even paid for one month to keep the billboards up. But even with the chief’s support, Hayes saw no progress on Angela’s case, which goes to show that one “good cop,” no matter how powerful, can’t fix a broken system. It’s all too real of a takeaway, given the real, pervasive mistreatment of victims. In fact, there’s federal legislation in the works that’s aimed at improving the reporting process for victims who come forward to the police.

Above all, though, is the concluding scene. Hayes teams up with Officer Dixon to track down and kill a man he overheard bragging about raping someone. As they’re driving to the man’s house, Hayes turns to Dixon and asks, “Are you sure about this?”

Dixon replies, “No, are you?”

Hayes says, “No,” as the film cuts to the credits. Even killing a rapist wouldn’t bring Hayes the closure she craved. This is a reality for so many victims; jail time or death could never undo the trauma done by acts of sexual violence, and closure is sometimes impossible to find.

As a notorious binge-watcher of Law and Order: SVU, I know mainstream media’s depictions of sex crimes are too idealistic. The police department is always on the victim’s side, and justice is almost always won in the end of. But Three Billboards felt real. It doesn’t glorify police departments’ role in obtaining justice, and it doesn’t solve the crime. It tells you a raw story about struggling to move forward from trauma.

But none of this is to say the movie didn’t have its problems.

The movie establishes racism as a pervasive problem in Ebbing, especially in the police department, then does little to confront it. Early on, Dixon boasts about using his power as a police officer to “torture” black people. Hayes calls him out on television, saying, “Seems to me the police department is too busy torturing black folk to solve actual crimes.” Later in the film, after Chief Willoughby dies, Dixon is fired by Willoughby’s replacement, Chief Abercrombie (Clarke Peters). If I’m giving director Martin McDonagh the benefit of the doubt, I’d say maybe this was his way of saying if you want to solve problems with racism, hire more people of color. But, since these are the only two memorable instances in which characters address racism as an institutional problem, I’d call my own speculation a stretch.

In a brilliant critique of Three Billboards in BuzzFeed’s Reader, Alison Willmore articulates the elephant in the room: “It forces you, as a viewer, to decide whether its desultory treatment of the black characters on the movie’s sidelines is worth tolerating in exchange for the satisfaction of its protagonist’s burn-it-all-to-the-ground fury.” This is a choice activists and victims of discrimination or physical violence should not have to make. Media reflective on our collective pursuit of justice should unite marginalized and historically oppressed communities, not pit them against each other.

This major point of contention with this film harkens back to the #MeToo movement. One of the main critiques of the impromptu social media campaign was its unacceptable overshadowing of Tarana Burke, a black activist who started the movement over a decade ago. Social movements’ lack of intersectionality isn’t new—racism is threaded throughout history, and less than a year ago, we were having these same conversations about the Women’s March.

The film got a lot of things right about the aftermath of sexual violence. Three Billboards tells the world of the injustices victims of sexual abuse face as they navigate the criminal justice system, criticizing police handling of sex crimes and ending without closure. The plot is dark, unjust, and difficult to swallow. As a survivor, I thought this film portrayed the painful and messy truth about sexual violence better than any movie or television show I can remember. Plus, they achieved this without depicting any sexual violence on-screen. But survivors—especially survivors of color—should not have to choose between racial justice and representation for victims.

Activists heard the critiques of the #MeToo campaign and answered with #TimesUp, where women of color were front-and-center. In addition to Oprah’s speech taking yesterday’s news cycle by storm, several celebrity women brought activists of color to the Golden Globes as their plus-one. Burke was one of several activists in attendance, in addition to Saru Jayaraman, co-founder and director of Restaurant Opportunities Centers United; Ai-jen Poo, executive director of National Domestic Workers Alliance; and Calina Lawrence, a musician using her art to draw attention to injustices faced by Native Americans.

It was encouraging to see Three Billboards recognized for the things it got right with regards to sexual violence. But it was even more encouraging to see celebrities sharing the spotlight with women who have been doing work on the ground against racism, classism, and sexual violence long before the 2017 #MeToo campaign or the Women’s March. I hope that someday soon we won’t have to choose between types of justice represented in film and television. The movement against sexual assault and harassment listened to critique and evolved; here’s to hoping Hollywood will, too.

(image: Fox Searchlight Pictures)

Tori is a freelance writer and a recent graduate of Emerson College’s journalism program with a minor in women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. Her work has appeared in The Boston Globe, Substream Magazine, idobi Radio, THINX’s Periodical, Culture Magazine, and more covering everything from politics to punk music to cheese. She’s an avid tea drinker, novice outdoorswoman, and a lover of the Oxford comma. Outside of writing, she loves traveling, reading, posting too many photos of her cat on Instagram, and binge-watching Netflix originals. You can follow her on Twitter and read her work on her portfolio.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]