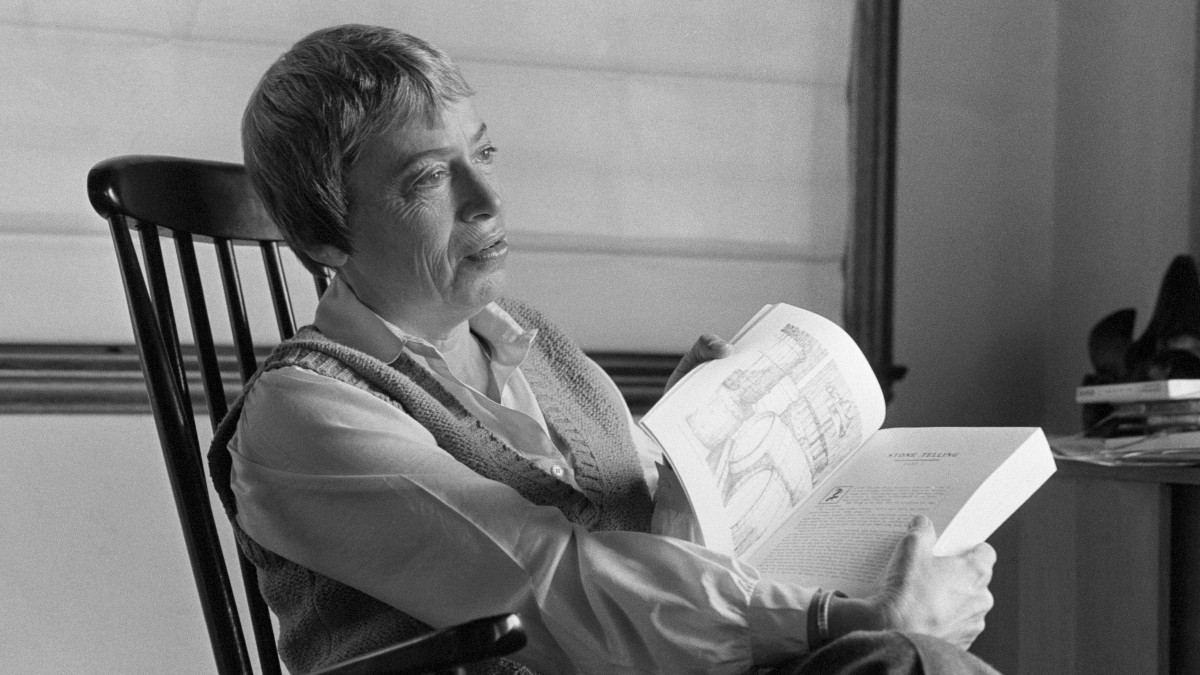

55 years later, Ursula K. Le Guin’s ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’ is still the gender binary-breaking bible

Science fiction leading light Ursula K. Le Guin has always gone against the grain. Whether it be filling the pages of her Earthsea children’s fantasy novels with a main cast of Black and Brown characters, or using her dystopian novel The Dispossessed to enumerate the benefits of an anarchist-collectivist society, Le Guin used her incomparable skills as a world-builder to challenge cultural norms.

In one of her most celebrated novels, The Left Hand of Darkness, Le Guin took a shot at one of the most all-encompassing aspects of the 1969 American society she was a part of: the gender binary. 55 years later, the novel still slaps.

The Left Hand of Darkness takes place on the distant planet of Gethen, one of the few planets yet to be assimilated into a loose hegemony of intra-galactic human worlds known as The Ekumen. Genly Ai, an emissary of The Ekumen, is dispatched to Gethen to convince its populace to join up with the organization and benefit from the myriad technological advancements that spacefaring society has achieved. Gethen’s initial response? No thanks, we’re happy on our own.

The people of Gethen are an oddity in the Milky Way Galaxy, the only subsection of humanity to be “ambisexual.” For the majority of their lives, Gethens are non-binary. They possess androgynous characteristics and only develop sexual characteristics during a brief fertility period known as “kemmer” that they experience monthly. While in kemmer, a Gethenian takes on male or female traits depending on potential partners that are also in kemmer in their immediate vicinity. A Gethenian may develop male sex characteristics while with one partner, and female sex characteristics with another. Every Gethenian has the potential to become pregnant. Every Gethenian shares in the responsibility of child-rearing. Every Gethenian, from a gendered perspective, is equal to every other Gethenian. For a human male like Genly, the societal implications are baffling.

While gender is a major component of The Left Hand of Darkness, it is not the focus of the book. The novel is a part political thriller, part religious text, and part story of survival. While living in the Gethenian nation of Karhide, Genly makes the acquaintance of the prime minister Estraven. While the pair begin the story hostile to one another, the ever-shifting politics of Karhidish society cause them to have to rely on one another to escape political persecution. In this sense, the world of Gethen is far from utopian. It is a world possessed by the human traits of greed, hatred, and suspicion. Traits that, despite what many societies on Earth would have you believe, are non-gendered. Le Guin is too canny a writer to paint any human world, even a non-binary world, as a paradise. And yet, she spends a significant part of the novel throwing out subtle hints that a non-gendered society is far kinder than its gendered counterparts.

One of the most mind-boggling discoveries that Genly Ai makes while exploring Le Guin’s genderless world is that Gethenians lack a word for “war.” Genly is shocked to learn that the reality goes far deeper: the concept of war is entirely absent from Gethenian thought. While Gethen is affected by political violence between nations, these “forays,” as they are called by the planet’s people, are fought between groups of hundreds, not tens of millions like in Earthling conflicts. While Le Guin never answers exactly why this is, her hints are clear: there are no men. Without a gender expressly devoted to war, the Gethenian’s political elite consider large-scale conflict so unthinkable that they simply don’t think of it at all.

Gethenians enjoy other similar, subtle benefits. No Gethenian is required to work while in kemmer, and Gethenians are free to sexually pursue others in designated “kemmerhouses” without societal shame. Free from a structure of thought that groups people into “protector” and “caregiver” categories based on arbitrary biological characteristics, each Gethenian can pursue their own life path while simultaneously enjoying the perks of a collective social net available to all.

At the heart of The Left Hand of Darkness is spirituality, which Le Guin explores equally from a non-gendered point of view. After learning of Gethenian religious customs from Estraven, Genly remarks that dualism, a concept prevalent across the majority of Earth’s various theologies, is absent from Gethenian thought. Light and Dark. Good and Evil. Yin and Yang. These concepts are replaced with a belief system that espouses the one-ness of all things. “Light is the left hand of darkness, and darkness the right hand of light”, reads an ancient Gethenian religious text. “Two are one, life and death, lying together like lovers in kemmer, like hands joined together, like the end and the way.” It’s a beautiful concept that is intrinsic to Gethenian beliefs across all of the planets’ countries and cultures.

Considering that non-binary and trans people throughout Earth’s history often take on spiritual roles, such as the Two-Spirit peoples of Indigenous North Americans and the Hijra of South Asia, Le Guin’s observation of the genderless/genderful nature of spiritual thought is powerfully relevant.

While The Left Hand of Darkness is cited as a hallmark of queer and feminist fiction, the novel is not without justified criticism. The most glaring fault of the novel is the use of the word “he” to describe any and all Gethenians, regardless of their current state of kemmer/non-kemmer. While at first Genly’s use of the word “he” to refer to Gethenians appears to be a clever nod from the author that her protagonist’s gendered brain is unable to conceptualize a world without sex, readers will be disappointed to know that Le Guin’s genderless aliens themselves use “he” to refer to one another at all times.

It isn’t a mistranslation of Gethenian language on Genly’s part, but an admission from the author herself. In her essay Is Gender Necessary? Redux Le Guin wrote that her decision to use “he,” what she then called “the generic pronoun,” was made because she “refuse(ed) to mangle English by inventing a pronoun for ‘he/she.'” It is a decision that, according to this rewrite of her essay, she regretted. A more subtle error, she admitted, was that while the Gethenians spend 22 days of the month in a non-gendered state, the novel only presents Gethenians in heterosexual male/female relationships while in kemmer. While Le Guin explained that homosexual sex would be “acceptable and welcomed” in any kemmerhouse, she admitted that “the omission, alas, implies that sexuality is heterosexuality.” “I regret this very much,” she wrote.

The Left Hand of Darkness is not a perfect novel. At times, it inadvertently asserts the systems of belief that it aims to destroy. However, I think that the historical context here is important. Darkness is a sci-fi novel that attempted to break the gender binary in 1969, a time when any attempt to do so in the real world was illegal and could be met with arrest. Though it may stumble, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness walked so modern feminist sci-fi could fly high into the stars and galaxies so lovingly dreamt of on its pages.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]