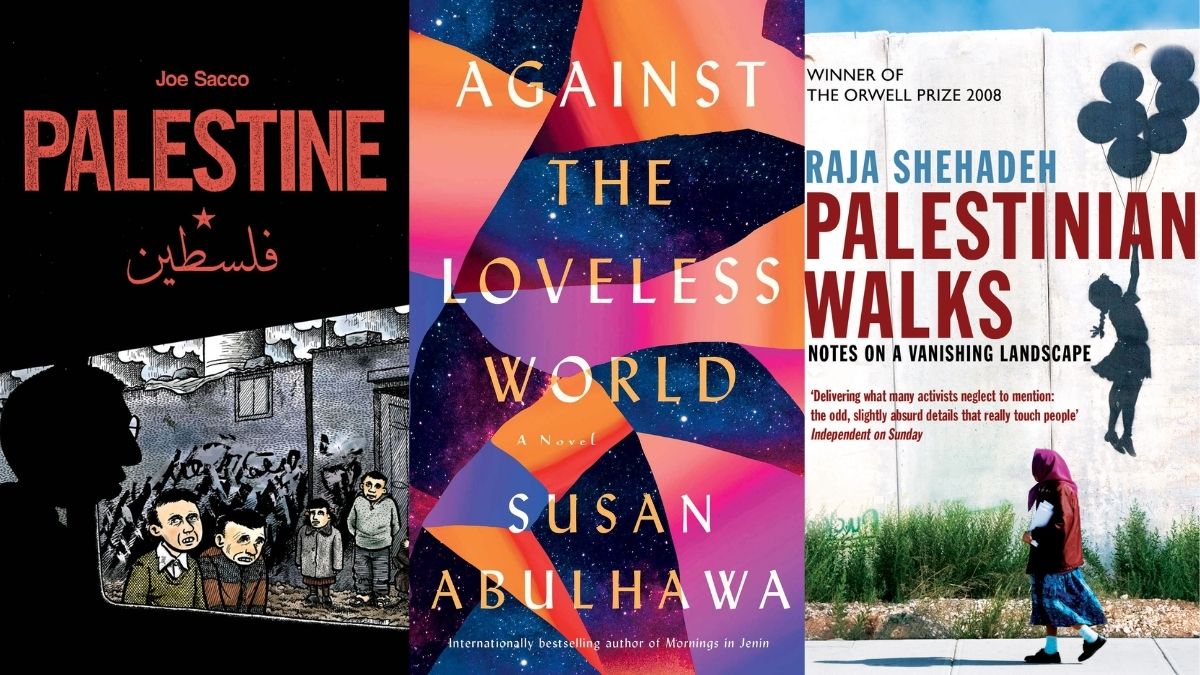

From Journals to Historical Fiction, 6+ Books About the Experience of Palestinians Under Israeli Apartheid

And why governments are all of a sudden distancing themselves from Amnesty International.

After decades of activists, journalists, and first-person accounts of the lives of Palestinian people within Israel’s ever-expanding border, Amnesty International formally recognized Israel as an “apartheid state.” Since the 280-page report went live on February 1, 2022, many organizations and governments that routinely cite Amnesty’s research (for policy-making and finding aid needs) have attempted to discredit it or disregarded it altogether. A few significant publications like the New York Times (which routinely defends Israel) barely acknowledge this report at all.

Within Israel’s globally recognized borders, some examples of apartheid practices include color-coded identification (license plates and IDs) based on religion, movement restrictions, segregated housing, and limits on housing permits based on religion, with Judaism above Christianity and Islam. Additionally, marriage laws limit interfaith and interracial marriage. Legal preference explicitly gives Jewish people (even those under narrow requirements) the right to become citizens and travel during COVID-19 restrictions. Some of these have random exceptions (like favors and labor needs), but these stand in a vast majority of all cases.

While outside of Israel, this is not the most popular stance, within Israel, many have admitted (either casually or with some regret) that Palestinians living in Israel, nationally recognized occupied zones, and more are treated as second-class citizens. Amnesty International reporting joins the Human Rights Watch and B’Teselem (Israel’s leading human rights group)—both of which recognized this status in 2021.

The weight of words

While the designation of an “apartheid” is linked very closely to South Africa, it is not limited to those geographical bounds. The intentions and outcomes of Apartheid in South Africa (based on race) and Apartheid in Israel (based on religion with bloodlines mulled over) are the same. Though now most people agree (at least out loud) that South African Apartheid is a bad thing and fail to recognize the subjugation of Palestinian people as a bad thing, people can’t put them together. Critics get accused of antisemitism because Israel’s national identity was founded in the Jewish faith and as home for Jewish people after the centuries of genocides leading up to the Holocaust.

Because antisemitism rhetoric has been embedded for centuries, I wouldn’t be surprised that (like misogyny and anti-Blackness) some people who call for Palestinian self-determination use antisemitic language. Even pro-Israel Christians do this. However, it’s difficult to engage with anything, considering any bad faith actor that understands these connections (and yet could also employ more overt antisemitism themselves) will weaponize this minefield—including the Israeli government. To speak against Israel is not to speak against all Jewish people within that country or anywhere in the world, just like it wouldn’t hold water to say the same for (example) Russia or China.

In honor of the beginning of April, which is MENA (Middle East and North African) Heritage Month, I put together 6+ books that give insight into some aspects of this experience, primarily from Palestinian authors. The experience of a people is not limited to their trauma. However, this list is about unpacking the effects of Apartheid on Palestinians (of various religious backgrounds), so it will be within that scope.

Against the Loveless World by Susan Abulhawa

Born in Kuwait to a family of Palestinian refugees in the ’70s, a series of conflicts (including U.S. invasions) lead Nahr back to her familial home in Palestine. Once there, she comes face to face with Israel’s occupation, and the state forces her into solitary confinement. Nahr’s story is heavy, but Abulhawa threads in moments of dark comedy and moral ambiguity to help her readers find hope. As the only work of straight-up historical fiction on the list, this novel may be easier to tackle for those looking for something other than non-fiction and graphic novels. In addition to her books, Abulhawa speaks about Israeli Apartheid and began non-profits projects like Playgrounds for Palestine.

Culture and Resistance by David Barsamian and Edward W. Said

This book features discussions and interviews with esteemed English literary scholar and one of the most high-profile Palestinians (other than DJ Khaled), Edward Said. Said’s academic texts are challenging to read and cover a wide range of time in world history. However, these transcribed conversational interviews focus on the most recent century of Palestinian resistance and thoughts on how both nations can realistically move forward and avoid more displacement and death. He discusses failed leadership, media propaganda, and world influence on this region.

I wanted to limit the non-Palestinian voices on this particular list. However, if this looks interesting, check out Except for Palestine: The Limits of Progressive Politics by Marc Lamont Hill and Mitchell Plitnick. These provide a distinctly American (Black and Jewish specifically) perspective on how taboo Palestine is to even discuss in the U.S.

Palestine +100: Stories from a Century After the Nakba edited by Basma Ghalayini

I mentioned this science fiction anthology book before in a list that contains the entry Iraq +100. The premise of this series is to collect stories from writers imagining what their home would be like in 100 years from a life-altering moment in recent history. Iraq +100 used a century after the U.S. invasion, and Palestine +100 used a century after “The Nakba.” Also referred to as “The Catastrophe,” this moment marked the first large wave of Palestinians’ forcible removal from their homes in 1948. About half of the Palestinian Arabs (est. 700,000+) were forced out of their homes the year Israel was founded. So, this novel imagines what life will be for Palestinians in the region during the year 2048.

The Hookah Girl & Other True Stories by Marguerite Dabaie

Dabaie’s graphic novel features a series of semi-autobiographical vignettes on how others perceive her identity as a Christian Palestinian American. She discusses the ways her cultures clash and how they are so similar. Dabaie opens the book with a note about how hard this book was to even get published. Dabaie’s existence was denied and made political as people took issue with her self-identifying as a Palestinian American. While not centering the conflict on the geographical level, I chose this book because it shows the rippling effects and social status of the millions of displaced Palestinians around the world.

Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape by Raja Shehadeh

The child of parents who fled Jaffa in 1948 (the year of the Nakba), Shehadeh grew up on the West Bank. As he grew up under an increasingly hostile and violent political landscape, he found solace in the freedom to roam and reflect on his surroundings. If you read Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson or another book featuring a human rights-oriented lawyer, this is an excellent addition. Like Stevenson’s book, Shehadeh is a lawyer (specializing in land law) that breaks up some of the more disturbing parts of the novel with a meditation back to the landscape.

As a winner of the 2008 Orwell Book Prize, the Orwell Foundation provided a list of more reading and other learning materials to accompany the book. These links included a short audio excerpt overlaying photos of the landscape as Shehadeh describes it.

Palestine by Joe Sacco

Of the handful of novels depicting apartheid structure from various legal jurisdictions within Israel and Palestine, Joe Sacco and his work consistently get brought up. Thus, I needed to include one of his books. Maltese comic-journalist Sacco published nine issues over two years depicting the lives of Palestinian people. His short stories feature individual stories and broader communities’ narratives.

Do you know a book that belongs on this list? Tell us in the comments.

(image: Fantagraphics, Washington Square Press, and Scribner.)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]