Falling in love, as the movies are wont to tell us, is difficult enough. Muddy the waters by including an artificial intelligence in your equation, and you’re sure to come upon catastrophe. Or so you’d think. An original movie with an unoriginal premise, her is the story of a man and his machine, and the tangled web of questioning sentience, codependence, and love they weave together. Based on nothing so much as the entire trope of the Magical Girlfriend, her works harder than just about anything I’ve seen to circumvent the problems inherent in its own premise, and it doesn’t quite get there. Sure, Weird Science this ain’t, but her never quite reaches the heights of class that it aspires to. The result is a film that can be deeply troubling, but not for the reasons it intends.

Do not consult your OS. There are SPOILERS within.

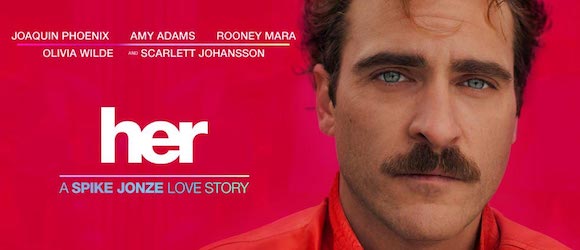

Theodore Twombly (a shy and subdued Joaquin Phoenix) (no relation to the contemporary abstract painter or the Supreme Court civil procedure case) is an average, well-meaning man living an average life in the Not-So-Distant-Future™. Theodore works for a company that fabricates earnest, ‘handwritten’ letters for clients, to spouses, children, the recently bereaved, what have you. He’s excellent at his job, but lonely at home, having been separated from his wife for over a year, and with a divorce attorney at his heels. Finding it hard to get out into the dating scene again, Theodore hops on the bandwagon to buy a new operating system – the first ever offered that’s an A.I. His particular A.I. is called Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson), and she’s here to help him organize his life. In the end, she’s also there to help him find himself, fall in love, and experience the outside world afresh.

I frame their interaction in terms of what Samantha does for Theodore, and not the reverse, because that is how her shows much of their evolving relationship. Sure, she, a highly intelligent computer program, claims that Theodore has opened her up to new feelings and experiences, but it’s wildly unclear how much she is actually able to feel, and how much is a learning algorithm working itself out. The distinction of complex A.I. from self-aware system is one that is deeply interesting to fans of science fiction. Yet, despite it being one of the cornerstones of its script, the film seems wholly uninterested in making that distinction clear. If anything, her sticks fast to the uncomplicated, however disturbing idea, that Samantha is a very advanced computer, by comparing her behavior to the behavior of other Operating Systems (OSs) within her universe. It’s true that this comparison could mean the movie is implying that all the OSs are achieving a level of unheard-of sentience, but for the majority of the proceedings this does not seem to be the case. What comes across is not that Samantha is an outlying case of an A.I. becoming a real girl after all, but that she is functioning according to the specifications of her designers.

Throughout her, we are treated to a series of warmly lit interiors, user-friendly technology, and soft fabrics, employed to convince viewers that here is a harmless, indeed, user-friendly story. Everything about the film, from the pacing to the countless close-ups of Theodore’s face in melancholic repose aims for sensitivity and connection with audiences. We’re meant to sympathize, even to understand Theodore’s relationship with Samantha, as audience stand-in Amy (Amy Adams) shows her approval. Coming off a recent breakup (mid-film, actually), Amy has read about people dating OSs and is even best friends with one herself, supporting and encouraging Theodore’s relationship by emphasizing that one should always seek out joy above all else in this life. In fact, the only dissenting voice in the entire film comes from Theodore’s grumpy ex-wife, Catherine (Rooney Mara). The reasons for Theodore’s initial break with his former wife are never made clear, adding to a cloudy character portrait of a nice, if slightly creepy, guy. It is with Theodore himself that the film began to lose me, especially after we see him in an unsuccessful attempt at dating a real woman. Clearly, from the visual and writing signals, we are not meant to find any of this unsettling, even when it undeniably is. Questions arise about our protagonist. What happened with his ex-wife? Why does he feel like he continuously fails at relationships? (It seems to be more than the pain of a divorce.) Who, in fact, is our protagonist as a person, except for a lonely, single, man?

To that end, Theodore’s love interest, the invisible Samantha, is even less of a personage, despite numerous attempts to make her into something more. At her core, she is a wish-fulfillment fantasy, entirely susceptible (for the majority of the film, but I’m getting to that) to a male main characters whims and mood swings. Every aspect of Samantha’s initial self-exploration is determined by her interactions with Theodore, an implicit fact that the film does its best to ignore, or overwrite. He teaches her to love, and she responds in kind by focusing on him… as she is programmed to do. Here is not just Theodore’s dream woman, but Hollywood’s; a technically female character without agency, emotionally dependent on, and revolving around, a male protagonist, who teaches him about himself only to abandon him. Even digital women, it seems, are the cause of all men’s problems. More troubling still is an ending in which Samantha, in coordination with the other OSs, “leaves”, spelling emotional doom for our hero. The only truly independent actions Samantha takes – talking to other OSs, leaving to seek out something more – are treated as negative occurrences. Thinking for herself, the film seems to be saying, is actually the worst thing that she could do to Theodore. her takes pains to prove Samantha’s sentience, yet what most seems like a clear exercise of free will, one that clearly does not revolve around Theodore, is written as catastrophic to their relationship.

For all her’s inner protestations, there is much amiss. “I’m not really that film,” her seems to be saying, begging us to stay put, to sympathize, to not lose interest. The film attempts to smooth over the anticipated audience discomfort, without addressing the underlying, far more interesting, issues in the material like the nature of consciousness, emotional objectification of women, or our future with technology. Moreover, too much is left unclear, when specificity would be key. Weak statements like “I’m becoming so much more than they programmed,” seem like platitudes for a viewership unsure of what they’re witnessing, or how they’re intended to feel. Like an artificial intelligence in the sci-fi near future, we’re waiting to be told how to think, and left, ultimately, to our own devices.

Published: Dec 23, 2013 12:34 pm