Presumably discontent with having an entertainment industry that is primarily focused on men, the NY Times lashed out at the Young Adult publishing industry Friday for having too many girl books.

Yes, you heard that right. In an article entitled “Boys and Reading: Is There Any Hope?” author Robert Lipsyte speaks about the publishing industry’s desire to “demystify to the overwhelmingly female audience the testosterone code that would get teenage boys reading,” and says that in order to get boys to read, they need to “be approached individually with books about their fears, choices, possibilities and relationships — the kind of reading that will prick their dormant empathy, involve them with fictional characters and lead them into deeper engagement with their own lives. This is what turns boys into readers.”

Because apparently what turns girls into readers is passing around copies of Twilight in between nail-painting sessions at fifth-grade slumber parties. Or something.

Lipsyte goes on to opine vague and unsourced “statistics” that say that boys don’t read, and states that teachers “don’t always know what’s out there for boys,” despite the fact that the vast majority of books taught in public school systems are written by men. Certainly when I tutored students, testosterone-coded writers like Walter Dean Myers and Chris Crutcher topped the list of reading assignments. But it’s not just teachers who are to blame for the gap in boys’ education–the publishing industry has apparently fallen down on the job by producing books targeted at young women. In the meantime, boys “don’t have enough positive male role models for literacy.” Someone alert David Levithan.

Lipsyte insists that boys are somehow shut out of the current boom in YA fiction because the industry is currently focused on writing books for–gasp–young women, a demographic that has historically been frequently overlooked by the publishing industry at large. Lipsyte’s distress comes despite a recent study which found that not only are the vast majority of young adult novels male-centric, but YA books have actually become more male-dominated in the last 100 years, not less. With only 31% of all children’s books published even having main characters that are female, this argument should be completely moot. Alas, Lipsyte’s just getting started.

Lipsyte ignores the undeniable fact that most books contain male characters, and instead lambastes the publishing industry for actively promoting girl stories: “at the 2007 A.L.A. conference, a Harper executive said at least three-quarters of her target audience were girls, and they wanted to read about mean girls, gossip girls, frenemies and vampires.” Note that 2007 was in the middle of the glut of paranormal romance brought on by the success of Twilight, which most industry insiders agree is now winding down. And given that the publishing industry is notoriously unable to predict what the next big trend in reading will be until it hits, it’s difficult to take this claim from 4 years ago seriously, considering that just in the four years since we’ve seen The Hunger Games, zombies, and the continued success of male writers like John Green and Cory Doctorow–none of which screams “girls only” to anyone with a brain.

Also, let’s remember that “chick lit” as a genre didn’t even exist until Bridget Jones’ Diary alerted the world that there might be room on shelves for stories about modern women dealing with modern issues that didn’t slot neatly into “romance” or “adult literature.” But chick lit, or its more industry-friendly title, “women’s fiction,” also cycled through its period of popularity, the way all breakout genres eventually do. Only one thing has remained consistent, and that is that books about men continue to sell.

Lipsyte has the audacity to whip out the tired and much-used argument that “it’s a cliché but mostly true that while teenage girls will read books about boys, teenage boys will rarely read books with predominately female characters.” Hollywood has been using this line for years to promote the systemic exclusion of female characters from cinematic narratives, and it’s as untrue now as it ever was. The danger of this line of thinking is that it creates a negative feedback loop that allows the industry to continue claiming that men don’t go see movies about women–because the industry won’t make movies about women for them to go see. The truth is that audiences want good stories, regardless of whether they have men or women at the center: or did the huge success of last year’s Alice in Wonderland not drive that point home?

Not for Lipsyte, apparently, who claims that “children’s literature didn’t always bear this overwhelmingly female imprint.” Leaving aside the question of what an “overwhelmingly female imprint” looks like, the truth is that children’s literature, more so than any other publishing genre aside from romance, has historically made room for female authors at times when they would have had to use a male pseudonym to have a writing career. Certainly female authors from Beatrix Potter to Beverly Cleary found a voice in children’s and YA lit long before it became acceptable for women to publish under their own names in other genres. And even so, literary giants like S.E. Hinton and J.K. Rowling were published under gender-nebulous initials, because the stigma against women writing about boys was so strong. Teens to this day still react in surprise when they learn that the author of the gritty, male-centric The Outsiders was a woman.

In an epic moment of point-missing, according to Lipsyte the success of those initial-only authors proves that women can succeed writing about men, after all; without acknowledging that it may instead be evidence to prove that publishing, just like every other industry, is harder to break into if you’re a woman, and twice as hard if you’re a woman who wants to write female characters.

Lipsyte longs for the days when female writers “wrote well about both genders.” (Has he read any books by women lately, we must wonder?) He lists Judy Blume as an example, ignoring the fact that most of her books addressed important isssues that many girls faced but no one talked about: periods, bra sizes, teen pregnancy, and female adolescence are hardly “non-gender-specific.” Somehow Blume passes Lipsyte’s nebulous de-gendered test, as does S.E. Hinton. He goes on to list Robert Cormier as an example of “what’s currently missing,” without considering that perhaps the reason no one is trying to be the next Robert Cormier is because students are still reading Robert Cormier.

Lipsyte doesn’t say whether, in the middle of this rosy time when the Paul Zindels (and Cynthia Voigts) of the world were writing acceptable books, he ever presented his son with Jerry Spinelli‘s Stargirl, a classic YA whose titular character unites an entire school for a temporary celebration of nonconformity. Granted, Stargirl was arguably one of the first manic pixie dreamgirls, and Lipsyte’s preference for Cormier’s non-redemptive writing means he probably tossed Spinelli’s humanist desert fairytale into the DNW pile. But Stargirl‘s enduring popularity proves that if nothing else, men can write strong female characters, and those books can find a place on the shelves of boys and girls alike. Much more recently, China Mieville‘s Un Lun Dun proved that a respected male sci-fi author can not only cross over into the dreaded all-female young adult category, but can successfully write about female characters saving the world. It’s not that hard, guys.

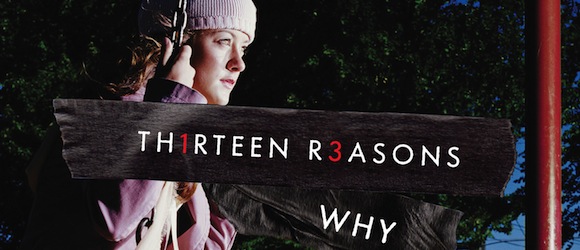

>>> Next Page: Thirteen Reasons Why, “Gendered” Stories, and After School Specials

Published: Aug 25, 2011 11:07 am