As we know from Verizon’s recent #InspireHerMind campaign, while 66% of 4th grade girls express an interest in science and math, women still hold less than 25% of America’s STEM jobs. But could television be a force to galvanize young girls towards science, technology, engineering, and math, and is it the job of the actors and writers who work on these shows to constantly push for better representation?

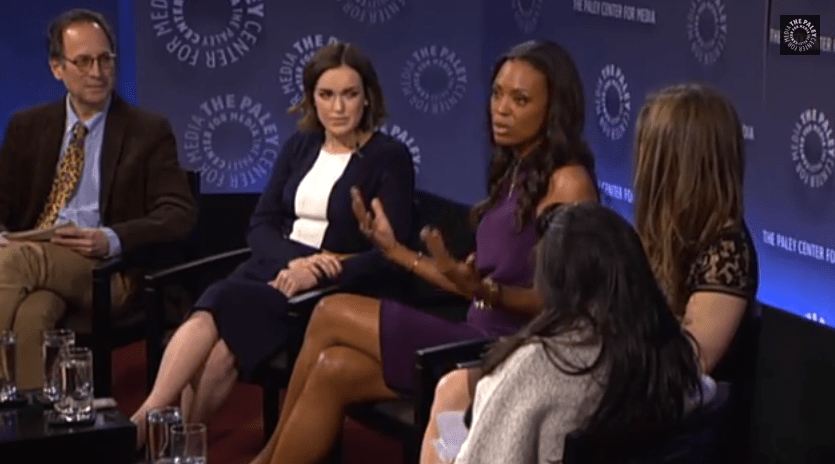

That was the question at the heart of Monday night’s Paley Center panel in New York, during which women from all over the industry—comedian Aisha Tyler, Agents of SHIELD’s Elizabeth Henstridge, and Silicon Valley writer Carrie Kemper —joined Girls Who Code founder Reshma Saujani and Paley Media analyst David Bushman to talk about their own experiences with STEM, their favorite scientific women on television, and what we might accomplish in the future.

After kicking things off with a clip montage and a brief introduction of everyone on the panel, Reshma Saujani opened up the conversation by divulging what first inspired her down her own career path—which, in addition to founding Girls Who Code, also involved her working as Deputy Public Advocate at the Office of the New York City Public Advocate, and even becoming the first Indian-American woman to run for congress in 2010.

“I knew I wanted to be a lawyer when I saw Kelly McGillis in Accused,” she said. “She was so fabulous! And if you think about it, in the 1970s, 10% of doctors and lawyers were women. Today that number is 45%. Why? Kelly McGillis, Ally McBeal, LA Law—we were constantly inundated by these fabulous women who were doctors and lawyers and we said, ‘I could do that.'”

Computer science, however, has had a considerable decline in gender parity since the ’80s, which is often attributed to how the personal computer was first marketed strongly to young boys as a toy to play with. However, it’s also in part, Saujani claimed, because of how we were “inundated with these dorky brogrammer dudes” like the ones from Revenge of the Nerds and Weird Science—and, nowadays, from Silicon Valley, the HBO satire that pokes fun at the deeply unsocial brogrammer culture of tech start-ups. While young girls might not be watching all of these different programs, Saujani noted, their parents often are, and can have a have a big impact in encouraging or discouraging their children towards certain fields of study.

As a new writer for Silicon Valley‘s second season, Carrie Kemper put in the position of having to defend the show’s adherence to the reality of the male dominated tech industry; while the show is hilarious, it also sparked a debate among feminist critics over its lack of women characters. “It’s a satire. There is this significant problematic gender gap in silicon valley, and I think this show is lampooning that,” she said, noting that it wasn’t as if the show’s core group of male programmers could be considered role models either. “I think to just stick a super competent female programmer in there for the sake of doing that isn’t what the show is about—and also, that character probably won’t end up being funny.”

The mostly male cast of HBO’s Silicon Valley. Not pictured: Amanda Crew, who plays the show’s sole recurring female (and non-programming) character.

But Silicon Valley will take advantage of the opportunity to include some more female characters, Kemper also noted; the writers were invited to sit down with twenty or so different companies in the Silicon Valley area, and Google in particular made a point to fill the room full of female engineers. “I think that we actually honed in on one girl who was very inspirational because she was a character. That’s what we’re looking for. We just want someone funny, and if going to Google and seeing all these women helps us, great!”

Aisha Tyler also noted that while diverse shows are “just more interesting,” than those that feature “group of people that all look and think and sound the same,” inspiring girls to achieve is something that can’t be solved with television alone. It’s a zeitgeist issue, she said, and one where the solution relies on parenting as equally as it does on culture:

I started in a totally male-dominated field ‘cuz I’m a stand up comedian. For the first fifteen years of my [professional] life, I was always the only woman on a line-up, always the only woman in a room. And I do think that this is a layered issue. We have to socialize girls to speak up. We have to socialize girls to be brave. A lot of times when a girl opens a room and there are ten boys in there, she won’t go in. WE have to socialize our girls not to fear that context and not to be intimidated by it. […]

We want girls to be precious and adorable and cute, and comedy is ugly and silly and embarrassing. We have to, as a culture—and especially as a parent, let your daughter know that it’s okay not to be cute all the time. It’s okay to be silly, it’s okay to ask questions, it’s okay to seem dumb, it’s okay to hit back—I don’t mean physically, but not to let a boy make a feel badly about yourself.

She also pointed out that similarly, there’s also no point in being precious with female characters when you’re the one writing them, particularly when it comes to video games. “A lot of people come to me because I’m really involved with the gaming world and say, ‘I want to write a female character, how do I do that?’ I say, ‘Just write an awesome character and then make her a woman.’ ”

“I don’t get up in the morning and thing, ‘I’m female, how do I feel about that?'” she added. “‘If I was a boy, how would I do it?’ I just do it.”

>>> Next Page: “TV is a very intimate relationship.”

Published: Dec 11, 2014 08:00 pm