The character of the femme fatale is one of my favorites. So why not put her in a contemporary YA novel? I certainly never thought twice about it when I was writing, but it does fly in the face of societal messages about girls and even the dreaded “likability factor.” Well, screw that.

I have always loved dark mystery stories – both hardboiled detective and noir. I grew up watching black-and-white film classics on AMC and was always drawn to noir’s shadowed cinematography, empowered and dangerous femme fatales, and tough and often bitter detectives.

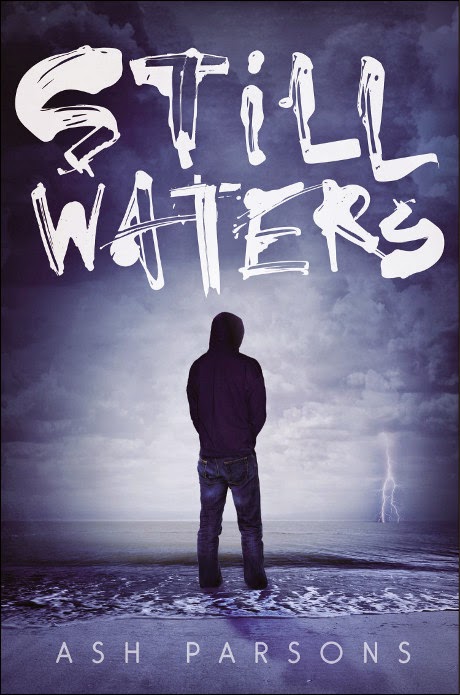

When I sat down to write Still Waters, I wanted to make it a believable contemporary suspense story. More than that, I wanted to use noir tropes to full effect. Few genres are as rewarding in their exploration of desperation and moral-ambiguity. I wanted to employ that to examine dark subjects.

Hardboiled and noir are related genres that continuously overlap – but let me take a moment to define noir – my most fervent love. The noir plot is distinct from “hardboiled detective” (think: The Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep, Chinatown, L.A. Confidential). Noir has more of a seedy underbelly. The pure noir plot is when the protagonist is caught up in the crime, not trying to solve it. In noir, the main character is the victim, perpetrator, suspect, or accomplice (think of the movie classics Double Indemnity or even Sunset Boulevard. Author Jim Thompson is the king of classic, gritty noir. For neo-noir look no further than one of my favorite authors, Andrew Vachss) (I was a librarian, so please excuse my mandatory book-rec moment).

One of the things I love about noir, both classic and neo, is how subversive it is and has always been. For just one example: take the stock character of the femme fatale. She is literally deadly, is usually sexually rapacious, and is the antithesis to Woman’s Day magazine covers. She remains subversive today, a dark counterpoint to societal messages about women’s bodies, strengths, attitudes, and choices.

In the classic movie Double Indemnity, the femme fatale (Barbara Stanwyck) has power and she uses it against the hapless men in the story. Although the third act defangs her, she is only triumphed over because she allows it. It’s an important distinction that she is never overpowered. Similarly, her film-noir heirs Kathleen Turner in Body Heat and Linda Fiorentino in The Last Seduction wield both their sexuality and their wills as one, lethal instrument, and they never relinquish control.

All these movie femme fatales are playing for high stakes, and every choice is their own. Although the “man-eating” monstrous woman is an archetype which obviously predates noir– the unique power of this particular noir trope is that we are drawn to see the destruction of the men. We don’t cheer for Fred MacMurray. We don’t wish for William Hurt or Peter Berg to be saved. We know that they are “getting what is coming to them” (darkest subversion indeed – to take the fairy tale message, usually aimed at girls and women, “don’t stray from the path or the wolf will get you” – and turn it on its head. In this case, the wolf is a woman).

Viewers were enthralled by the power of these characters when women were most often portrayed as stalked, abused, powerless, or in need of rescue. It was subversive to see women with sexual agency – even if they were demonized for it. It was subversive to see a man taken in, gamed, and defeated – even if he was supposed to be “the good guy.”

The femme fatale has become a trope of the noir/hardboiled genre, one that the protagonist and the reader are both aware and leery of. Often the reader or character will wonder if a woman is a femme fatale or a damsel in distress? Or she both? In the film of James Ellroy’s book L.A. Confidential, Lynn Bracken (Kim Bassinger) is inscrutable at first. We may sense a connection between her and Bud White (Russell Crowe) but we also sense an underlying tension beyond the sexual. He is a cop, she is a prostitute, etc. As the story unfolds, their lines get tangled, and he doesn’t know if he can trust her, and we don’t know if we can trust her, either. It is of course, Ellroy’s conscious choice to make it confusing, drawing as he is on the history of noir/hardboiled – where we aren’t sure which role she is playing.

In Still Waters I wanted to cross genres and exploit the power of noir tropes for utmost effect. We respond to tropes and their larger archetypes because we recognize them, and so it is rewarding to see a trope played out, as well as to see it subverted. Therefore I wanted to both fulfill reader-expectation, and in some instances subvert it.

In the tradition of Ellroy and other noir authors, I combined tropes in several places. The first is in the character of Cyndra, who seems to be both a damsel in distress and a femme fatale. The protagonist, Jason, is never quite sure the depth of her feeling for him, even as they become more entwined. It was my goal to show some of Cyndra’s conflicted inner-life while keeping her inscrutable to Jason.

Another major thing I wanted to do was to subvert and combine tropes by flipping masculine gender roles at the starting point for the story. Since Still Waters is set in high school, I had the absolute luxury of writing characters that could be believably subdued or threatened by the adults around them. In that way, my three main characters each become “the Damsel in Distress.” So Michael, who is being threatened by an adult criminal, is in distress. And Cyndra, while she is in love with (or in thrall to) Michael, is likewise threatened by an adult in her life. Finally the “tough guy” – the brawler with a heart of gold (more trope-play, there) – Jason (and his sister Janie) are both endangered by their father. This distress-triangle means that each of these characters starts the story on the same footing – with one part of a trope already encoded into their actions. It’s a commonality that hopefully makes their characters more rich while at the same time subverting reader expectation. At the end of it all, I hope readers recognize that just as in life, we are all a combination of impulses, and even the toughest of characters can be endangered, while the most seemingly-fragile person can have a core of iron.

Ash Parsons’ first book, Still Waters, follows seventeen year-old Jason, who has a reputation for being the guy that no one messes with. As tough as he is, though, all Jason truly wants is to survive living with his abusive father until he turns eighteen—and can take his younger sister Janie away somewhere safe. So when one of the popular kids at school offers him fifty dollars a day to hang around with him, Jason sees a golden opportunity to save up for his getaway. As he gets drawn in deeper, the stakes get more dangerous and soon even his fists aren’t enough to keep his head above water. Still Waters is an intense, gritty drama that pulls no punches—yet leaves you rooting for the tough guy.

Still Waters is available now.

Ash Parsons has been involved in Child and Youth Advocacy since college. Recently she taught English to middle- and high-school students in rural Alabama. Watching some of her students face seemingly impossible problems helped inspire her first novel, Still Waters. Additionally she has taught creative writing for Troy University’s ACCESS program and media studies at Auburn University. Ash lives in Alabama with her family. Still Waters is her first novel. Follow Ash Parsons on Twitter @ashparso.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: May 1, 2015 06:00 pm