The following was originally posted on Read ‘Em and Weep! and has been republished with permission.

This is a long one. At first glance, it may look like a critique of Brian Azzarello’s Wonder Woman. And it is, although there are many aspects of his work I don’t touch upon. But it’s actually a discussion of the almost-universal Paternal Narrative, the scarce-as-hen’s-teeth Maternal Narrative, and the way female-centric stories are represented (or not) in DC Comics and elsewhere—all seen through the lens of Wonder Woman #1-35.

“We’ve cleaned her up. You can describe who she is now. She’s got the specific description now just like Batman or Superman. She’s the daughter of a god.” – Brian Azzarello

In heroic literature there is a tradition called the Paternal Narrative, also known as “Luke I Am Your Father” Syndrome. (I’d say Patriarchal Narrative, but that word is used in so many different contexts that its meaning gets overloaded.) It states that, if a hero’s parents are important to his story, the father will be of most importance; the mother will be secondary or even irrelevant. The father may be a powerful man—heroic or villainous—from whom the hero gets his skills, personality, or powers. The hero will try to measure up to, oppose, reconcile with, or redeem his father. The mother may be given some interesting backstory, often after the main tale is told—or not—but mainly exists to link child and father.

This is, of course, common throughout the primary tales of Western literature (Hercules, Jesus), modern popular culture (Luke Skywalker), and certainly mainstream comic books. It’s rife in DC Comics, and always has been.

As a child, Hal Jordan sees his test-pilot father deliberately and heroically crash his plane to save innocent people on the ground. Jordan goes on the become a test pilot, and then, as Green Lantern, a great hero, overcoming fear and risking his life for others just like his father did. Can anybody tell me what Hal Jordan’s mother did? Did she have a job? Raising three sons as a single mother is an eminently respectable and difficult thing to do, but the Hal Jordan story does not highlight or even depict this in any way, or suggest how it causes Hal to become the hero he becomes. It does not drive the narrative or the characterization.

If you read Superman over the decades, you see Jor-el as the most brilliant scientist on Krypton, who predicts Krypton’s destruction when everyone else gets it wrong. He is the creator of the spaceship that takes the infant Kal-el to Earth, as well as virtually every important invention on Krypton, including the Phantom Zone projector. In some stories he gets to come to Earth briefly before Krypton explodes and be a proto-Superman. Silver Age stories traced his ancestry through a lineage (all male) of amazing scientific minds. Throughout all this, Lara is… his devoted wife.

Modern stories may try to flesh out Lara a little more—she’s a member of a warrior clan, she comes from an important family too. (She’s even given a maiden name!) But it doesn’t add up to much, and it doesn’t stick. Read this description of Jor-el from The New 52’s World’s Finest #27 (“The Secret History of Superman & Batman”), published in the “post-feminist” year of 2014: “[He] strode across the giant planet like a titan, a last genetic remnant of the ancient days when their sun was strong, their lives long, and their deeds a song of glory.” (Admittedly Lois Lane, telling the story, mentions that this is Clark’s version, and he “always did tend to overdo the melodrama.” But she doesn’t contradict him.) Here’s Lois’s report on Clark’s description of his mother: “—“. In this particular story, Jor-el’s attempt to save Krypton results in its premature destruction, and Lara has to suggest that he use the tiny rockets he has built to save some children. But none of this is played for irony; Lara and Lois still praise his brilliance, courage, and integrity. Certainly nobody thought the story might be centered around Lara instead.

In every version of Krypton that we’ve seen, children take their family names from their father—it seems to be a default for all worlds in the DC multiverse. And so we have Kal-el, Kara Zor-el, and characters who wind up being named Kon-el and H’el despite their more tenuous relationship to the family. There are countless references to the House of El. The House of Van? I can’t tell you much about that.

Bruce Wayne sees both his parents murdered before his eyes, and admittedly the image of his mother’s pearls falling to the ground is common. But when he sits in the Frank Miller chair in Wayne Manor, bleeding to death, he calls out to his father—not his parents—for a supernatural sign that he shouldn’t die. And he constantly encounters busts of his father in the house; they must have had a mold made. In some Silver Age stories, Thomas Wayne dons a costume and acts like a proto-Batman. Martha Wayne, like Lara, has been given a little backstory in recent years, but the idea that in any version of Batman—Earth 1, Earth 2, New Earth, anywhere—his mother would be the admired doctor from a wealthy family, and his father a helpful sort who uses his spouse’s money for philanthropy, seems outside the character’s mythos. And would inevitably be condemned by some as “too P.C.”.

The Paternal Narrative applies to female characters as well. Kara Zor-el’s father was, for most of his existence, a literal twin of Jor-el, both biologically and as a character. He saved Argo City, created the Survival Zone, and built the rocket that sent his daughter to safety and her superheroic role. If you want to know how much thought went into her mother’s role, look at her name: Alura. She’s alluring, we get it. (In some stories, especially the New Krypton saga, she gets to do more. These are not typical or lasting.) Helena Wayne, the pre-Crisis On Infinite Earths Huntress, is the daughter of both Batman and Catwoman—but is generally known as “the daughter of Batman,” as he is a far more important and better-known character than Catwoman, who is essentially a member of his supporting cast. (The Huntress’s origin, including the death of her mother, was built around Selina Kyle’s fear that her husband Bruce Wayne would judge and reject her for unwittingly killing someone in the past. He judges, she fears.)

After CoIE, Helena Bertinelli’s origin as the Huntress was based on the fact that her father was a Gotham City mafia boss; her heroism is defined in opposition to his criminality, and her struggle not to be as brutal as he was. If her mother is anything other than “the wife of a mafia boss,” I’ve never heard it. (In one storyline Helena discovers that her father was actually a different mafia boss, who had an affair with her mother. This revelation is a key point in the plot. Her mother is still a cipher.) In The New 52, the Huntress is again the daughter of (Earth-2’s) Batman and Catwoman. But count the number of times she mentions her father compared to mentioning her mother. She was Robin to his Batman. Batman’s life on this Earth is, as usual, of vast importance; he, Superman, and Wonder Woman died saving the world, and there is a grand statue celebrating their sacrifice (Earth 2: World’s End #1). Catwoman is unceremoniously blasted out of existence by a parademon, and people don’t really talk about her after that. When Huntress, corrupted by an evil New God, confronts her grandfather Thomas Wayne, she screams “Where were you when my father died?” Presumably she remembers that her mother died too, but she doesn’t mention it. (Oh, yes, it turns out that Helena’s paternal grandfather, Thomas Wayne, is alive, and takes on the Batman identity after his son dies. Catwoman’s remaining family, if any, is not part of the narrative. It’s all daddy stories around here.)

Jade was a popular (and much-missed) DC superhero, the daughter of Alan Scott, the Golden Age Green Lantern, and Rose Scott (nee Canton), the briefly reformed supervillain Thorn (the Golden Age “Rose and Thorn”). Jade’s powers, down to their color-coding, were taken entirely from her father, and her storylines were heavily influenced by her relationship to him—their finding each other, accepting each other, becoming truly father and daughter. Her mother, believed to be dead, showed up for one arc and then conveniently died. There was a single 8-page story that toyed with the concept of her having some of her mother’s plant-based powers, but it was immediately forgotten because it didn’t fit in with the character concept: Green Lantern’s Daughter. (Her brother Obsidian’s powers—shadow-based rather than light-based—were not derived from their mother either, but from the influence of either the villain Ian Karkull or the alien force Starheart, depending on the story. And his stories also heavily Alan-Scott centric. Really, their mother could have been anyone.)

My examples are taken from DC superheroes, but they don’t need to be limited to them. From my earlier days reading Marvel, I know a great deal about Reed Richards’ father Nathaniel—his time machine, his disappearance, his schemes. I know nothing about Reed’s mother. Indiana Jones spent an entire movie having an adventure with his father, leading to their reconciliation. I suppose he had a mother at one time. For three “episodes,” Luke Skywalker yearns for, recoils from, and is finally saved by his father, from whom he inherited his midichlorian powers. His mother is not even mentioned until the following three prequels, where she exists mainly to explain Anakin’s character development; she dies in childbirth, and her specific character traits and history have no direct impact on Luke’s story—and she has no powers to pass on. Clark “Doc” Savage, Jr…. Well, you get the point.

There are some exceptions. Aquaman inherits his powers and royalty from his mother, although I feel sure that readers are far more likely to remember his lighthouse-keeper father; Atlanna’s fate—and powers, if any—were always so vague and mutable to making it hard to say exactly how she influenced her son’s heroism . (Another aquatic hero, Namor the Sub-mariner, was more influenced by his mother. These stories were inspired by old legends of human men taking mermaid or selkie brides.) Some second-generation heroes avoid the father-based narrative—Infinity, Inc.’s Fury (Hippolyta Trevor) was the daughter of Wonder Woman and the entirely human Steve Trevor; after Crisis on Infinite Earths, she was ostensibly the daughter of the earlier Fury (Helena Kosmatos), although there are large gaps in that story that never got filled in. (Digression: this is one reason I was unhappy when The New 52 took hold—mysteries from the previous continuity would never be resolved.) Other legacy characters, however, such as Jesse Quick, were based on their fathers even when both parents were superheroes. In any case, these examples pale in comparison, in both number and narrative strength, to the far more common Paternal Narrative.

And now I’ll tell you a secret: I am not opposed to the Paternal Narrative. I’ve used it myself sometimes. It’s familiar. It resonates with stories familiar to us from childhood, from Greek myths to Biblical tales. (Admittedly those stories stem from sexist cultures, but most of us are not about to throw them out.) It is useful in some cases precisely because it does not challenge assumptions that a writer may not wish to engage with in a particular story. It even has a (weak) “bioliterary” excuse: given the facts or pregnancy, it’s easier to write a story in which characters are surprised by who their father is than by who their mother is. Although I’m not sure “easy” is always the best storytelling choice.

What I am opposed to is the Paternal Narrative’s relentless ubiquity, the way it can be expected to pop up in almost any story. It is so standard, so easy to make a key element of a story be:

- “The hero’s father was a hero/villain/adventurer/inventor…”

- “The hero wishes to live up to his or her father’s example; or is afraid of becoming just like his or her father…”

- “The hero’s life changes when he or she discovers that his or her real father is…”

Fathers, in these stories, have significant traits, character arcs, influence. Mothers are generally far less well defined, mainly used for their biological function: she gave birth to the father’s child. Not much more needs to be known. The message this communicates is that the hero’s father has a vital and specific role in his child’s narrative, the mother a generic role that could be played by any non-specific woman. Men’s personalities drive the narrative, whether the hero is male or female; women give birth, and don’t need much of a personality. (A mother with a strong personality would often get in the way in a story like this. It’s no surprise so many die in childbirth, or not long after.)

There was exactly one well-known, easily recognized—“iconic”—DC superhero (not second-generation, not a legacy) that not only avoided the Paternal Narrative, but subverted it, presented us with a real counterpoint to it. Exactly one, and that was Wonder Woman.

Wonder Woman—Diana—was the daughter of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons. Hippolyta raised Diana, trained her, taught her the Amazon values. She continued to be an important presence in her daughter’s life. In many ways, Diana’s strongest ongoing relationship was with her mother.

Her father? He is, at best, implied—some man with whom Hippolyta had a relationship or marriage in the past. He is not named; he does not have highly-defined, specific characteristics. In some versions of the “clay origin,” he doesn’t even exist. In any case he is not a significant part of Diana’s story. He does not bestow upon her powers, motivations, or her family name. This is the inversion of the Paternal Narrative, the one story—one!—that implicitly challenges the assumption that that father’s character and actions are of primary importance, and the mother’s a distant second.

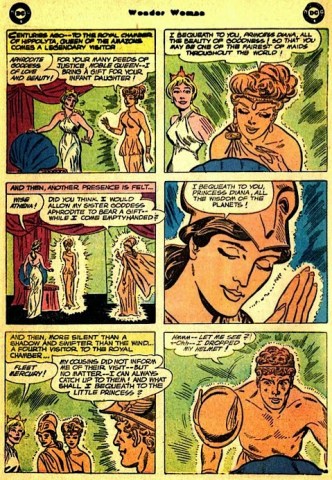

There’s more to this challenge. Diana is raised on Paradise Island, where her mother and her Amazon sisters have created a healthy and loving society. They worship the goddesses of Greek myth—in the early stories, Aphrodite, goddess of love, defined in opposition to Ares, the god of war; in later stories, a collection of Greek goddesses including Aphrodite, Artemis, Athena, Demeter, and Hestia. The goddesses grant Diana her amazing powers. (In some versions Hermes is involved, and in one that I can remember, Hercules; but usually it is one or more goddesses.) The Amazons are trained warriors, quite capable of fighting to protect their home and innocent people. But they prefer love to war, and when possible rehabilitate their enemies instead of killing them. (They have a whole island dedicated to it!) These are the people who, along with Hippolyta, taught Diana their ways.

None of this is an accident. William Moulton Marston, who created Wonder Woman, was, for all his personal idiosyncrasies, a feminist. (Ah, another overloaded word!) He believed in the value of women, a value not based on men. He wanted to depict an image of what women might accomplish if not subject to oppression, discrimination, and male supremacist assumptions. Wonder Woman was not simply a story of One Exceptional Woman who is as good as men—that’s a sexist stereotype exemplified in the early superhero teams (Justice Society of America, Justice League of America, Teen Titans, Fantastic Four, Avengers, X-Men) which, at their inception, each had several male members with varying personal characteristics, and one female. No, Wonder Woman was about more: the value of women and of female relationships, unimpeded by male authority. Even Etta Candy and the Holliday Girls, often seen as comic relief, were a formidable group of young women: brave, loyal, and willing to fight for the good.

This was a radical idea at the time, and was certainly not reflected in any other mainstream comic book. It was partially hidden behind some of the weirdness of Marston’s Wonder Woman stories, with their emphasis on dominance, submissions, being getting chained up, and the like, but it was central to his vision for the character.

And the idea is still important and meaningful today. Some people may insist that we actually do live in a post-feminist world, where men and women are judged on the same criteria and have equal opportunity in all things. But it’s not the case—not in the world, not in the U.S.A., and certainly not within the context of DC comics. Yes, we have more female characters than we used to; teams now have more than one female superhero. And women characters have a wider range of personalities and roles than they used to. But, as my earlier examples showed, the Paternal Narrative—and its implicit message—still dominates. And if you make a list of New 52 comic book series headlined by an individual hero, you’ll find far more male superheroes than female. If you take away the headliners who are based on, or spin-offs from, male characters who are far better-known and more important, you are basically left with Wonder Woman. She is the one headlining female superhero who is independent of a male progenitor in the literary sense. We haven’t exactly reached Peak Female Superheroes yet. Marston’s message is still important.

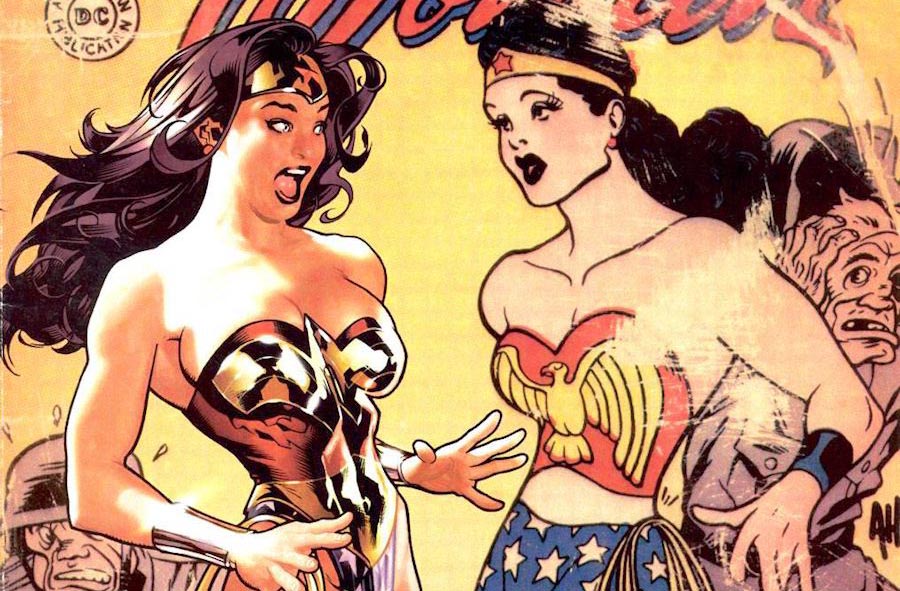

Over the decades Wonder Woman has gone through many variations, like most superheroes with a lengthy publishing history. But through it all she maintained her female-centric origin and hero’s journey: her powerful, significant, influential mother; the Amazon sisters she learned from; and their goddesses. She was essentially the only exemplar we had of the Maternal Narrative, in which the hero’s mother, in all her specificity, plays an indispensable, long-term role, and her father is secondary or even irrelevant to her story.

The New 52

Until The New 52, and Brian Azzarello and his editors, with their need to “clean [Diana] up” and give her a “specific description”:

“We’ve cleaned her up. You can describe who she is now. She’s got the specific description now just like Batman or Superman. She’s the daughter of a god.”

You can see what’s been added to give her a specific description: an important father. You can also see what’s been dropped from the description: any mention of her mother. In four sentences Azzarello has eliminated the only serious Maternal Narrative we had, and replaced with with a Paternal Narrative, of which we already had a multitude.

Now I, along with many others, might suggest that Wonder Woman already had a specific description: “Diana, daughter of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons, is granted great powers by the goddesses of Greek myth, learns the skills and values of her Amazon sisters, and brings them to the larger world as the heroic Wonder Woman.” Although barnacle-like details have been added over the years (as they have been to all major superhero origins), I never found this core description confusing, or something that needed to be cleaned up. It’s only “broken” if you judge it by the all-encompassing expectations of the Paternal Narrative: I don’t get it, where’s the crucially important father? But in many ways that was the point.

Of course, Azzarello did not simply give Diana an important father. He gave her a father who is one of the two great patriarchs in Western culture and literature (the other being God). Here are some comparisons between Diana’s father and mother:

- Zeus is far better known to the general public.

- Zeus, king of the gods, is far more powerful and influential than Hippolyta.

- Zeus, rather than the goddesses prayed to by Hippolyta in previous versions, is the source of Diana’s great powers.

He overshadows her in every way. In comparison, Huntress’s parents Batman and Catwoman are practically equals.

But maybe this elevator-pitch version of Diana doesn’t do Azzarello’s vision justice. Instead, let’s look at the 34-issue story he tells.

In this story, Azzarello seems totally uninterested in Queen Hippolyta and the Amazons she rules. By issue #4, Hippolyta is turned into a stone statue, and the Amazons into snakes. They appear in a few flashbacks (more on that later), but they play no role in the story until they are restored in issue ## 29. A mother with a strong personality may just get in the way of the Paternal Narrative, so she’s set aside. Diana does not make the restoration of Hippolyta and the Amazons a priority; she rarely speaks about it. She certainly never seeks out any help from colleagues she may know (such as Zatanna) to see if they can help. When Orion arrives, she does not ask him if his New Gods might be able to reverse the curse that has incapacitated the entire community she grew up with. It doesn’t seem to be on her mind, or the writer’s.

Diana, you see, is busy with the world of Zeus. Although Zeus is not physically present (as far as we know), every single character in the story with the exception of Orion is there precisely because of their relationship to Zeus: his lover Zola (and later son Zeke), his wife and sister Hera, his brothers (Hades, Poseidon), his children from Greek myth (Apollo, Hermes, Artemis, Athena, and so on), his newly-invented modern children (Lennox, Milan, Siracca, etc.), plus a few more like his grandson Cupid. Every one of them is reacting to his actions: getting Zola pregnant (which drives Hera and thus everyone in opposition to her) and vacating the throne (which drives the many relatives who want to rule Olympus). Even in his absence, he is the pivot point around which the entire plot turns. This is the Paternal Narrative writ large, although there turns out to be even more to it in the end.

I was perhaps hasty when I said that Azzarello wasn’t interested in the Amazons. He does quickly have them all turned into snakes. But that doesn’t stop him from reversing any value they ever had as a loving community of women independent of men, as created by Marston.

When Diana first travels to Paradise Island, with an injured Hermes in tow, we hear a voice: “Can you smell it, sisters? Our air be putrid with musk. Aye, what hangs between the shanks now fouls my nose. Perhaps I shall take my blade and separate the offense from the offender. Leave them to shrink and wither on the sand.” When Wonder Woman speaks against this, the voice asks “Who dares?”, as if no one would.

The word balloons are distorted and not associated with any character. When I first read it, I thought it was the spirit of Paradise Island itself, which would have been somewhat damning. Reading on, I guessed it was Aleka. But in any case it is the first words we hear from any Amazon, and none of her sisters contradict her in any way. Even her queen doesn’t chastise her for threatening castration against a male guest (and a god, at that). I don’t think we ever hear an Amazon speak a contrary opinion; Aleka’s floating voice is the only one the writer gives us on the subject. If it’s not the common Amazon view, why not let us hear from someone else? As it is, this depiction of the Amazons has enough editorial support to spread to other series and writers: in her first appearance, in Demon Knights #1, Exoristos, an exiled Amazon, says “I come from an island where men are castrated and women are pleased.” This seems to pass for casual conversation among the New 52 Amazons.

(When I speak of “the Amazons,” I am excepting Diana, who seems different from them and not representative in her opinions.)

This happens to be a common sexist stereotype of independent or feminist women: that they hate all men to the point of wanting to castrate them. It brings to mind Rush Limbaugh’s “man-hating feminazis.”

But Azzarello’s depiction of the Amazons as man-haters goes much further. Later we learn that, to replenish their ranks, they go to sea, board boats crewed by human men, and seduce them. Then we see an image of the Amazons holding their swords to the necks of these men: “Their lives… are drained from them,” and they are thrown overboard, dead. (The most reasonable interpretation is that the Amazons kill them; they don’t actually look “drained,” by sex or magic, when they’re being threatened by swords.)

Nine months later the Amazons give birth. The girls they keep; the boys… apparently, the Amazons are willing to kill them too. Fortunately, the (male) god Hephaestus rescues them, trading weapons for the infants, and raising them to work in his smithy, where they say they are not slaves; they are artists, and happy. One says that without Hephaestus, they would have been “thrown in the tide — to drown, unloved.” Hephaestus proves to have the empathy that the Amazons entirely lack; he mentions that his mother (Hera) cast him out to die, and because of that experience he could “never allow” that to happen to the unwanted male children of the Amazons. He’s a good guy. They’re murderers. And Hippolyta is the queen of the murderers.

(The murders seem completely gratuitous. Perhaps the Amazons are worried that sailors, left alive, might follow them back to Themyscira. If so, there’s an easier way to do all this. Take a boat to an island or the shore of a continent. Liberate some local clothes. Have sex with a man. Go home. Is this beyond them, or do they just like killing men?)

These goes beyond sexist stereotypes, and begins the echo the views of paranoid misogynists. I am reminded of Pat Robertson’s quote: “Feminism is a socialist, anti-family, political movement that encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism and become lesbians.” (I am not suggesting Azzarello shares these views, only that he finds them useful, and somehow appropriate, in a Wonder Woman story.)

And so one of the core themes of Marston’s Wonder Woman—that of the value of independent (dare I say feminist?) women, their relationships, and what they can accomplish together—is entirely repudiated. Independent women, rather than creating a healthy and loving community that the world (and Diana) can learn something good from, in fact become man-hating, castration-loving malefactors who murder the men they use to impregnate them and would likewise murder their own male infants if a kind (male) god didn’t offer them a better deal. They are essentially supervillains. Wonder Woman and the rest of the JLA should capture them and lock them up.

Admittedly, Azzarello does not directly tell us that all communities of independent women would turn out this way. He simply takes away the one example we had of a good community of such women, and replaces it with a horrific one. Just as Aleka’s voice seems to represent all Amazons, because none of them contradict her, so too do these vicious Amazons seem to represent all communities of independent women—because there are no alternatives within the world of the narrative. The change he has made to the Amazons of Paradise Island—who have always had an extremely significant symbolic and thematic role in the Wonder Woman saga—is so enormous, and so ugly, that one looks for some suggestion that they do not symbolize a theme opposite to Marston’s: that a community of independent women would be evil and murderous. In vain. The only thing to compare them to is Hephaestus and his assistants, a community of happy artists brought together by the compassionate god who saved them from the evil women. And that community is all male.

Doctor Bifrost is a software engineer, writer, reader, activist, and big-time nerd. He was brought up on The Lord of the Rings, The Left Hand of Darkness, Greek & Norse mythology, and comic books, which he’s been reading since he was four. He’s still running a D&D game he started in 1982. Doctor Bifrost enjoys well-thought-out world-building and nice merlot. He can be reached at [email protected].

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: May 14, 2015 10:30 am