Where would you even start if you had to begin describing the current state of video games? For many people, this question would be answered by turning to the voices fighting to make video games a more inclusive, progressive, and safe community to be a part of. Others would answer by looking at the games that push boundaries, be they technological, sociological, or cultural. For others still, this could be a question of pure financial viability, demographic shifts, and market growth.

There are many answers to this seemingly simple question, and all of them are worthy of discussion in their own right. Obviously, there isn’t one single answer to the question of, “What is the video game industry like now?”

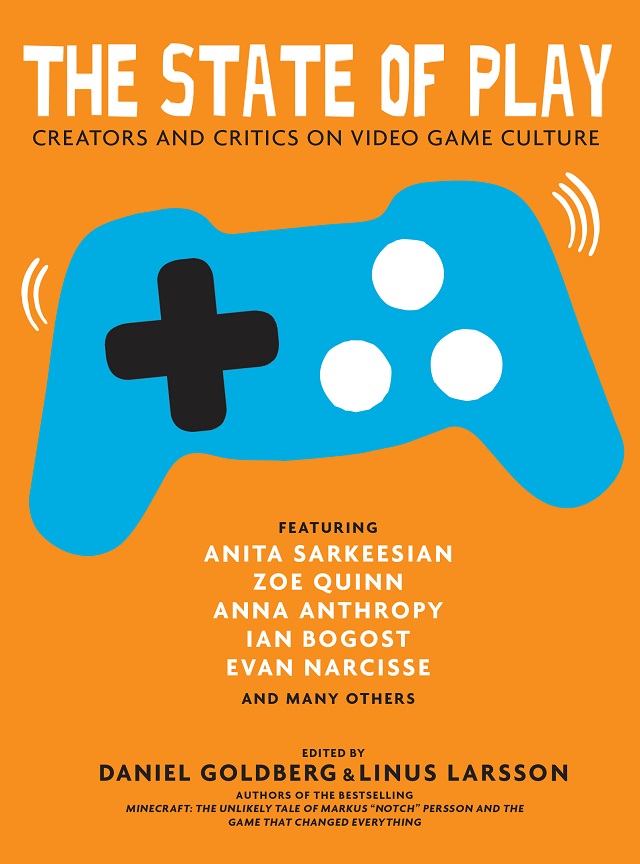

This is where The State of Play: Sixteen Voices on Video Games, edited by Daniel Goldberg and Linus Larsson and published by Seven Stories Press, enters the picture. It tackles this question by providing a multi-faceted response to it. To put it simply, there is a lot going on in video games right now.

Goldberg and Larsson are names to know when it comes to critically examining the cultural impact of video games. Their English-language debut was the bestselling book Minecraft: The Unlikely Tale of Markus “Notch” Persson and the Game That Changed Everything. In their new book, The State of Play, Goldberg and Larsson compile different chapters written by sixteen prominent and respected voices in games criticism and tackle a much wider scope than a single video game and its creator. As its name suggests, The State of Play attempts to show just what is being talked about and happening in video games right now.

The State of Play has a heavy progressive bent, because it believes that the discussion around video games should be more than just conversations on escapism and technology requirements and advancements. To answer the question of what are video games like now, The State of Play offers a nuanced and challenging view on just how video games—and the culture surrounding them—have grown up in its relatively young history. It isn’t a very large book, and for its size, it takes on the way we view and discuss video games in a big way.

Each chapter, written independently of the ones preceding or following it, addresses a certain aspect of video game culture that the respective author deems worthy of discussion. The overall book doesn’t really offer a unifying argument but rather is content to let the authors discuss their chosen topics however they see fit. At times, this is seamless and the flow of ideas is logical and enjoyable to pursue.

However, there are a few instances where the roughness of the approach shows through. Notably, this occurs when one chapter in the latter half of the book presents an argument for why we should even be discussing games in the first place (a point that, while important, would be better served in an introduction and not halfway through a book that is proving this very point). If anything, the book suffers from a lack of strong organization that leaves it feeling uneven at times—but only slightly.

But as a book that includes some critical heavy hitters and thinkers in video games, such as Leigh Alexander, Evan Narcisse, Cara Ellison, Brendan Keogh, and many more, these few moments of roughness are forgivable; the writing and ideas presented by each chapter are so strongly argued that it’s a delight just reading well-written essays on both video game culture and video games themselves.

Perhaps one of the best, or at least my personal favorites, is “Ludus Interruptus: Video Games and Sexuality” by merritt kopas. This chapter is kopas in full form and consistently on point, discussing a topic that’s hard to talk about when it is talked about at all: how is sex presented in games and why is it this way? kopas offers a witty, earnest, and open discussion about why sex has been so awfully portrayed in major games and where we can look, in both AAA and indie circles, to find alternatives to these otherwise bland examples of sex.

Beyond this, though, kopas asks a question that I think is near the core of major conversations surrounding video games. That is, why are we so willing to accept non-consensual violence in shooters and other games as the norm, yet freaked out and pushing away from consensual violence in games that look at positive representations of BDSM? Rather than providing concrete answers, kopas invites the reader to be challenged by these ideas and grapple with them in their own way.

This challenging of the reader to engage and grapple with these concepts is also found in “What It Feels Like to Play the Bad Guy” by Hussein Ibrahim, who not only examines representation of Middle Eastern people in shooters but also introduces readers to how popular video games, particularly shooters, are in Lebanon. Ibrahim interrogates the way uninformed stereotypes operate in a context that may be unfamiliar to readers and shows how vibrant and viable non-Western markets are for games—and why many mainstream shooters need to step it up in fixing their lazy, stereotypical representations of both people and the Arabic language.

While The State of Play features eclectic and distinct voices, there are two major kinds of essay: those that look at how cultural epochs have historically shaped aesthetic aspects of games and those that look at how contemporary cultural discussions are currently fighting to change game aesthetics. What this looks like is that some essays are personal narratives on representation of race, gender, and sexuality in games (such as in kopas and Ibrahim’s respective chapters, “Your Humanity Is in Another Castle: Terror Dreams and the Harassment of Women” by Anita Sarkeesian and Katherine Cross) compared to less personal chapters that give video games the close reading treatment (such as “Game Over? A Cold War Kid Reflects on Apocalyptic Video Games” by William Knoblauch and “The Squalid Grace of Flappy Bird” by Ian Bogost).

While at first the shift in tone between some of these chapters is a bit jarring (going from a sociopolitical look at why we enjoy violence in games by Ellison and Keogh to an axe-to-grind chapter on the design of Flappy Bird by Bogost initially creates a disconnect in flow), all the chapters in this book share the same goal. Every chapter in The State of Play is, in some facet, arguing that we cannot view cultural paradigms as distinct and aesthetically and ideologically separate from video games. Whether it’s Cross and Sarkeesian discussing the violent harassment they’ve experienced as women in gaming or David Johnston explaining his methodology behind creating maps for Counter Strike competitions, there remains a shared ideology to be teased out—that video games are played by humans and therefore reflect and inform both our virtual and real interpersonal relationships. Once realizing this, the disconnect between confessional writing and close reading mentioned earlier seems less egregious.

This is what makes The State of Play so good to read. Knoblauch’s expert analysis of the reason why video games are so fascinated with the apocalypse and post-apocalypse illustrates the way video games can operate as a reactionary medium to real-world circumstances. And this is given the same weight and importance as Evan Narcisse’s personal testament as to why video games need to get better at representing black people both as fully-formed characters and in terms of visual representation. One way of talking about video games is not prioritized over another. Any way of looking at video games is valid in The State of Play—as it should be.

The State of Play is a brave book, not just in content that challenges what video games are capable of being and becoming, but also in its structure. As eclectic as the content is, so are the way the chapters are written. Anna Anthropy’s chapter on the importance of Twine is written like a traditional “Choose Your Own Adventure” print book, with directions provided for the reader to follow as they choose. Zoe Quinn writes about her experience making Depression Quest and the harassment she received in second person, an attempt at putting the reader in her position. Ellison and Keogh’s chapter is written as endearing and cheeky letters to each other, which simultaneously questions the prevalence and point of violence in games while also having fun with the discussion in order to disarm readers. Whether or not some or all of these writing styles are effective depends on the reader, but it presents a unique way to try and get readers to engage with the material on an intimate level.

The State of Play doesn’t just say that diversity of identities, content, mechanics, and ways of talking about games is important—it supports this statement by providing that very diversity. And as video games currently work toward including more voices, different stories, and greater variety in the ways we tell these stories, this kind of eclectic book matters. A lot.

The State of Play is available October 20th, 2015 from Seven Stories Press.

Kaitlin Tremblay is a writer, editor, and gamemaker, whose work focuses on feminism, mental illness, and horror. You can find her writing, books, and games on her website, That Monster, and listen to her talk about old 90’s tactical RPGs on Twitter at @kait_zilla.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Aug 20, 2015 02:42 pm