Few horror directors loomed as large in the late 20th century as Wes Craven: the original Nightmare on Elm Street took the gut instinct dream logic at the bowels of many a horror film and made one of the most iconic films of the slasher genre, unintentionally nudging the genre toward “gimmick killers” along the way; Scream not only revived slasher aesthetics in the 90s but kicked off the popular wave of teen-dramas-with-murder and the still lingering love for meta commentary on horror tropes.

Those are the name brands. But beyond that he managed to start with some of the then-most brutal (and still pretty cringey) films of the 70s—The Last House on the Left and The Hills Have Eyes—to weaving an increasing amount of pathos into the writing of his films’ victims. Craven’s “Final Girls” always felt like real people, and even the expendable meat had considerably more going for it than any filmgoer would’ve expected from the genre. When Craven took a sudden left turn to do Music of the Heart in the late 90s, it almost made a weird kind of sense to me (looking in retrospect, of course). If there’s a bizarre mashup that characterizes Craven’s body of work, it’s definitely “horror with heart.” The world’s a rather smaller, sadder place without him.

All that in mind, I thought it would be fitting to spotlight a few of his lesser known films, ones which hold a special place in my heart. Let’s all, horror and film fans alike, toast a great artist.

A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987)

Kristen is stalked through her dreams by Freddy Kreuger, leaving wounds that lead her parents to believe she’s at-risk for suicide. After being checked into a hospital for closer watch, she meets Nancy, who not only believes her but is prepared to teach Kristen and a small group of likewise-haunted teens to combat Freddy in their dreams.

While every NOES film has at least some element of intriguing visual distinction to it—a haunting bit of effects work, a particularly good death, good old fashioned camp hilarity; hell, even the awful remake had Jackie Earl Haley acting his wonderful heart out—it would not be unfair to say that it by and large falls into the law of diminishing returns after the first installment. The Wes Craven directed ones are always the exception.

Dream Warriors is a shining example of a film sequel: it builds on the character and world development of the first film, doesn’t retread the same narrative beats as the original story, and ups the stakes by approaching a familiar subject (the dream killings) in a new way (as a winnable rather than merely survivable).

Craven’s choice to bring back first-film survivor Nancy as a mentor to the new batch of teenagers suffering from deadly dreams is a well-executed stroke of inspiration, as Heather Langenkamp brings a weary determination that anchors the film through its outlandish dream set pieces. The new kids are all acted well enough (to say “for the genre standards” feels a bit cruel, but there you are), and the fantastical elements are always engagingly inventive when they are not horrifying. This film is just on the edge of Freddy the Stand Up Comedian, with far more quips than the first film but enough menace to keep the inevitable deaths from losing their bite. Well worth the watch for any fan of the first flick.

The People Under the Stairs (1991)

(Available on Netflix)

Pointdexter (aka Fool) lives with his family in tenement housing on the verge of eviction. Desperate for money, he’s talked by local con Leroy into helping to break into a nearby wealthy house with some deeply creepy owners. Caught off guard and trying to hide from the murder-happy proprietors, Fool finds that he’s not the first child to be trapped in the house.

I’ve waxed poetic about this film before, but I wanted to give it a brief nod here as well.

The nice thing about Wes Craven, appreciable even when other parts of his films aren’t working, is that he actually gives a damn about his characters (the Nightmaremovies under his direction are several cuts above most of the slasher genre on the point of ‘likable human beings’ replacing the usual cast of expendable meat). And that’s most of what carries Stairs as well: Fool (and I could be wrong, but I’d say this is pretty much the only horror/thriller with an African American protagonist before 2010’s Attack the Block) is resilient and kind, young and desperate enough to have been believably strong-armed into the scheme that kicks the movie off but well served by the brave and compassionate impulses that got him into trouble in the first place. He’s immensely likable and easy to root for, no small feat for the film amongst its genre brethren, and the movie allows itself enough moments to breathe that we can actually feel something like a rapport between Fool and the children he meets in the house.

While definitely in a place of tonal oddity between survival horror and 80s adventure film, and probably a good 20 minutes too long, it’s bursting with an odd sense of dark humor and clear love for its gaggle of child protagonists. A mixed bag to be sure, but one that’s never dull even when it fails, and is almost too charming for words when it succeeds. Don’t be shy, internet. These are the movies lazy Friday nights are made for.

Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994)

Heather Langenkamp, a bit weary of the cult of popularity from her role in the NOES films, has been receiving strange calls from a voiceless stalker. The people surrounding the films have also found themselves afflicted, reporting strange obsessions or inexplicable accidents which are rapidly becoming deadly.

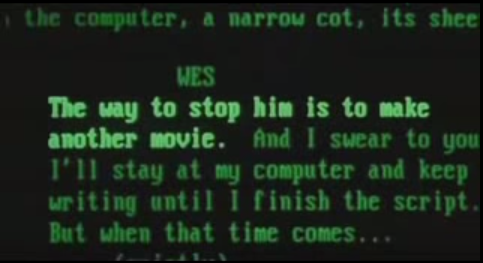

“Freddy Kreuger breaks into the real world” is a really, really hard pitch. I can practically hear you folks cringing as I type it. But there’s a reason I like to think of this film as “the better Scream”—and that’s because Scream is the movie Craven made when he realized a movie commenting on a long franchise was apparently daunting to new viewers (had a bit of a tough time at the box office, this one).

And it’s such a shame, because this film managed to balance a more toned down version of the meta commentary on the defanging of horror and how the telling of scary stories is a part of our culture, mixed it with actors-playing-themselves whose performances all but bled the strange, sometimes resentful but mostly loving relationship they’ve had to this franchise (and the deep camaraderie they have with one another). It’s not just horror but an attempt to poke at why we tell horror stories, nodding to its slasher roots and regressing back until it’s the id of children’s dreams and old Gothic fairytales.

All it takes is a passing familiarity with the first film in the series to understand this one, a minimal barrier at best in the modern era, though of course better franchise knowledge is bound to increase the number of little nods recognized. It’s such a simple point of entry for a film that’s one of my horror favorites for the whole decade, one that’s never gotten credit for how dark, beautiful, and smart it is.

Red Eye (2005)

Flying back from her grandmother’s funeral, Lisa is blackmailed by a mysterious man claiming to have snipers outside her father’s house. His demands: that Lisa use her connections as a hotel manager to move the incoming US President into position as part of an assassination plot.

This was Craven’s love letter to Alfred Hitchcock, and a fine letter it was. The script’s arguably the most streamlined the director ever worked with, relying heavily on the claustrophobia of the setting and the nuanced performances of Rachel McAdams and Cillian Murphy, both of whom deliver in spades. As you might’ve guessed by the influence name drop, it’s more thriller than horror, with the third act shifting into one hell of a cathartic action sequence.

It clips along at a fleet pace while also lingering in moments of nigh unbearable tension, and Craven’s fondness for relatable, agency-wielding heroines is in peak working order. And my but Cillian Murphy is in fine form throughout, wielding his delicate good looks and firm handle on uncanny menace to full effect to sell the “of course she couldn’t have suspected this would happen” angle. It’s a dynamite picture, cut down to be as lean and harrowing as possible without losing the emotional hook that pulls you through to the bombastic end.

Want to share this on Tumblr? There’s a post for that!

Vrai is a queer author and pop culture blogger; between this and the cancellation of Hannibal, their inner horror buff will be mourning for the foreseeable future. You can read more essays and find out about their fiction at Fashionable Tinfoil Accessories, support their work via Patreon or PayPal, or remind them of the existence of Tweets.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Sep 5, 2015 11:02 am