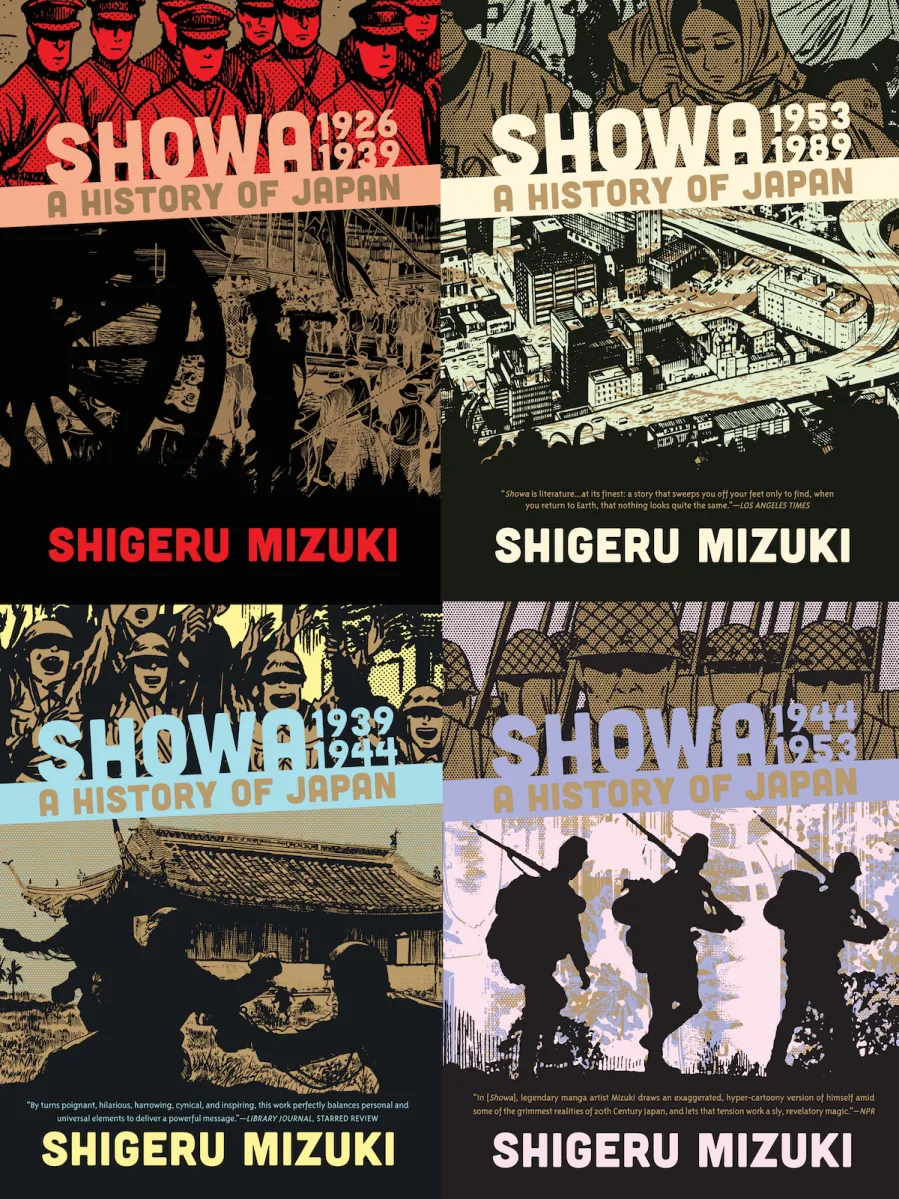

How does one even approach reviewing a masterpiece that stretches across four volumes and more than 2,000 pages? Shigeru Mizuki’s Showa: a History of Japan is just such a piece, and it occupied the entirety of my summer.

Letting Mizuki’s voice and images wander around in the back of my mind for less than six months seems like the least I can do. Although, truth be told, his work has echoed in me for much longer than that, and I expect to carry it with me for the rest of my life. Great artwork—be it literature, painting, song, or comic—just does that. It lingers.

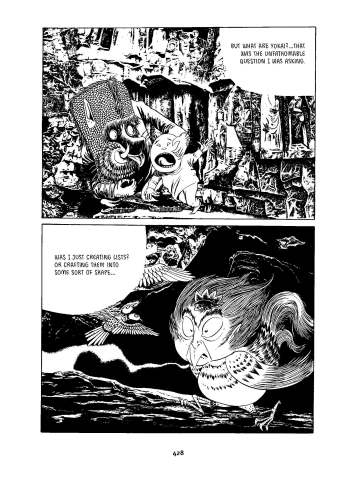

Mizuki, winner of the Kodansha Manga Award and numerous Eisner awards, is perhaps most well-known for GeGeGe no Kitaro, a manga series that follows one-eyed yokai Kitaro and his graveyard fellows. (Yokai are spirits or monsters from Japanese folklore, and they’ve many different forms and functions. Mizuki is fascinated by them, and they show up in much of his work.) Kitaro has been made into several anime series and movies, and if you haven’t yet seen it you should definitely look it up.

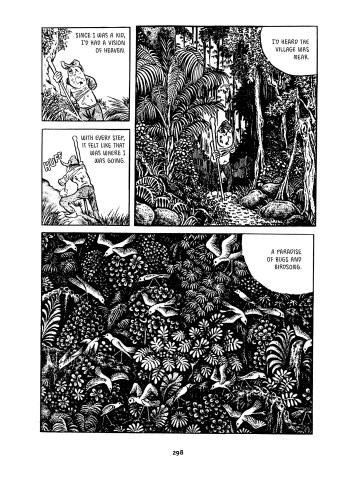

I first encountered Mizuki’s work when I was assigned a review of Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths, his bleak and scathing tale of Japanese soldiers sent to the South Pacific during World War II. Not a light read by any means, but I was enchanted with Mizuki’s storytelling prowess. His signature art style pairs hyperrealistic environments with very simply sketched, caricature-like figures. The characters may not be immediately likable—focused as they are upon base humor, food, and sex—but they’re very human, and they feel very real. After all, they’re surrounded by death, and their existences have narrowed to the basics. And then, their lives are thrown away. It’s impossible to read Onward without internalizing the horrors of war, at least as much as anyone who hasn’t experienced it firsthand can.

As powerful as Onward is, it pales in comparison to Showa, in which Mizuki tells the story of Japan’s Showa period (1926–1989) and of his own life, from the Great Kanto Earthquake to the death of Emperor Hirohito. The amazing thing about Showa is how comprehensive it is. A lot happened in the 20th century, after all! Catastrophic natural disasters, war, peace, booms and depressions and more. Most histories that I’ve read follow one track through those events: the balcony or the dance floor; the textbook or the memoir. Mizuki gives his readers both.

To ease the transition from the ant’s view to the bird’s, Mizuki provides his readers with a guide, Nezumi Otoko (“Rat Man”). Nezumi Otoko will be familiar to Mizuki’s faithful readers, as he’s one of Kitaro’s yokai friends. In Showa, he functions as the omniscient narrator, peeking into global events and Mizuki’s personal life with equal curiosity. Sometimes he plays the outsider, interviewing his subjects to solicit their public responses, and sometimes he smoothly reveals their inner thoughts. In all things, he’s the reader’s advocate, patiently explaining the connections between the world’s big events and the daily lives of Japanese citizens. In many ways, Nezumi Otoko seems to be Mizuki’s older self, revisiting his past with the advantage of hindsight.

To be frank, Mizuki’s experience during WWII was horrific. He falls off a cliff into the ocean, he catches malaria, his friends and compatriots are slaughtered, and his arm is amputated after it becomes infected with maggots. Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths is based on his time in the South Pacific, but Showa bares it all. He is, perhaps, hardest on himself. In his own eyes, Mizuki is a hapless fellow drifting through life, motivated mostly by food. In the third volume of Showa, Nezumi Otoko explains, “‘Noble Death’ is headquarters’ answer to almost everything. Shigeru Mizuki only escapes that fate by fantastic luck. It is like some magical thread of destiny pulling him from death’s door over and over again. He has nothing to do with his own survival.”

Showa’s translator, Zack Davisson (an acquaintance of mine) once told me that working on Showa was a heck of a lot of work, but also a labor of love. He queried publishers for a couple of years until Drawn & Quarterly took the bait and agreed to bring him onto the team. Having spent a lot of time with Showa recently, I completely understand why Davisson was so passionate about the project.

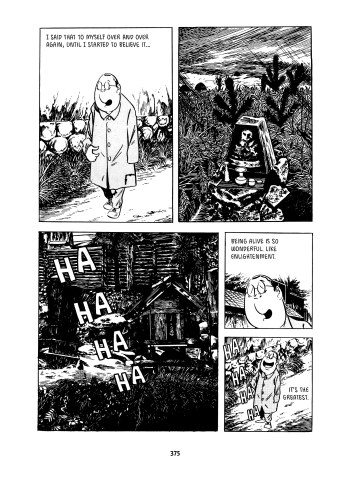

By the end of these four volumes, Shigeru Mizuki has become very dear to me, and I doubt I’m the only one for whom that’s true. Mizuki bared his soul, and to some extent the soul of Japan, to his readers. As we know through his work, he’s intelligent and humble and bumbling and well-meaning. He’s confused and curious and passionate. He seeks security and creative fulfilment, even when those two things don’t necessarily go well together (as many artists know). Famed mangaka he might be, but Shigeru Mizuki is as human, and as flawed, as we all are.

Although he’s unrelentingly critical—jaded, even—of the government, the military, and economic structures, compassion underlies Mizuki’s every word. There are many individuals who committed atrocious acts over the course of the 20th century, but there is no villain to this story. There are people who were blinded by pride, by power, by foolishness, and by many other things, but the events of the world are big, and individuals are small. As Mizuki says, “… but I couldn’t be angry at the emperor. He meant nothing to me. It was the system I was forced into that I hated. War is so much bigger than any one person, anyways …”

The English translation of Showa’s first volume was published by Drawn & Quarterly in November, 2013; the final volume hits the stands today, September 29. I highly recommend that you add it to your reading list.

Amanda M. Vail is a writer, editor, and consumer of as many comics as possible. In addition to running her business, Three Wrens, she’s a staff writer for Women Write About Comics. Follow her musings on Twitter @amandamvail.

(image via Drawn and Quarterly)

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Sep 29, 2015 05:02 pm