Brooklyn Nine-Nine is one of the best comedies on television right now. Not only because it’s hilarious, or because of its cast’s diversity and the show’s constant challenging of gender roles, but because it allows us to spend time with good police officers and laugh, even as it examines the public’s complicated relationship with the police in a post-Ferguson United States.

Since the show began in 2013, I’ve been in love with the show for its talented cast, and its humor – particularly the way in which it will make you think it’s going in one direction (Boyle’s “nice guy” obsessively pining for his colleague, Rosa, knowing she’s not interested) then subverts your expectations by going somewhere else (Boyle’s apology to Rosa is an awesome homage to moving on and appreciating friendship).

The current national outrage against police brutality began simmering as early as 2011, as Occupy Wall Street protesters faced increasing violence in cities across the country. Photos of police spraying peaceful protesters directly in the eyes with pepper spray, or being physically violent with them, began to make the rounds. Police brutality became more a part of the public consciousness.

Then the summer of 2014 came along, and 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot by a police officer in Ferguson, MO.

Unarmed black men being shot by the police wasn’t new, nor were other forms of police brutality – and they certainly weren’t new in Ferguson – but Brown’s shooting sparked a national outcry against a system that allows for this kind of police violence against civilians to go unchecked. It became more and more difficult to respect the police when there are not only so many bad cops popping up in the news daily, but an entire system of supposedly “good cops” doing nothing about it, for fear of breaking the “Blue Wall of Silence.”

When The Heat came out in 2013, I was thrilled that a comedy had arrived with two female leads (Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy) playing police officers in a buddy-cop film, which is generally a male-dominant genre. However, I never saw it in theaters – though it didn’t need my help, as it opened at #2 at the box office and ended up grossing almost $160 Million. My enthusiasm for the film, solid and funny though it is for the most part, waned when I finally watched it on Netflix in 2014. By then, Ferguson had happened. And suddenly, I found the violent outbursts of a white police officer – female though she may be – a lot less amusing. I wrote about the experience over at Beacon.

Meanwhile, I kept my eye on Brooklyn Nine-Nine, because I wondered if they would acknowledge the shifting public attitude toward the police. For its first two seasons, the show seemed to ignore public perception of the police entirely, perhaps in an attempt to maintain a comedic safe haven for folks who just didn’t want to think about it. Yet, I saw that as the show’s one flaw. Ignoring such a clear and loud national conversation seemed like a missed opportunity; especially on a show that had a lot to say about underrepresented groups.

In the show’s third season in a recent episode called “Boyle’s Hunch,” Brooklyn Nine-Nine has finally addressed the issue in a way that only it could, and it was a revelation in its simplicity.

In a story line involving Captain Holt in his brief stint as PR director for the NYPD, he is charged with coming up with an ad campaign that inspires people to have faith in the police again. His idea is to have a model officer pose for a poster campaign, and he chooses Amy to do it. She, of course, is thrilled that her idol is choosing her to be a representative of upstanding cops. Gina, meanwhile, makes no bones about expressing her disagreement with the entire idea, saying that people need more than just pictures of smiling cops to feel better about the police. “This campaign, like three out of five Backstreet Boys,” she says, “is inconsequential.” After Holt tells her that she needs to help facilitate or leave, she replies with, “All I’m saying as a, if not the Voice of the Streets is…this t’ain’t gonna work.”

Turns out the Voice of the Streets was right. After the posters have gone up all over the city, Amy comes into Holt’s office with photos of defaced posters that people are posting on social media, all of them less than favorable. In a typically Amy Moment, she points to one and says, “This one says DIE PIG, and they didn’t even put a comma between Die and Pig.” Holt realizes that he was wrong about the campaign. And to her credit, Gina doesn’t tell him “I told you so.” (Instead, she wears a shirt into his office that says “Gina Told You So” on the back, so she didn’t have to say anything.)

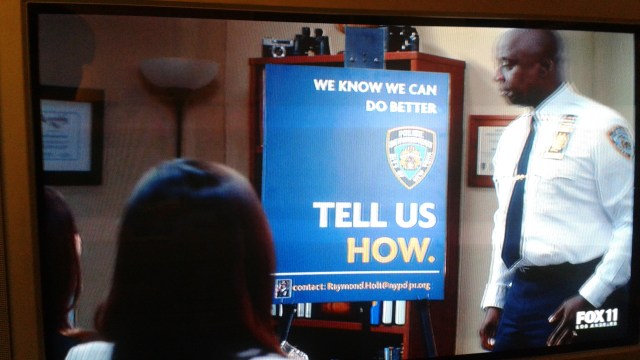

Later, Holt rethinks his strategy, and comes up with the poster in the screen-cap above: “We Know We Can Do Better. TELL US HOW.” While it won’t solve all the NYPD’s problems, the message could go a long way by demonstrating that the NYPD is listening (rather than continuing in its usual demands for respect without giving any in return), and that they value the concerns of the citizens they’re sworn to protect. Holt vows to read every email he receives.

If only the real-life NYPD was this open to criticism.

Leave it to a show like Brooklyn Nine-Nine to allow its black, gay police captain to demonstrate one of the NYPD’s greatest flaws; its white, female civilian employee to voice an objection; and the captain to realize the error of his ways and point toward the beginnings of a solution by using a slogan arrived at by a Latina detective. This is how you do comedy, and this is how you address real-life concerns on television in a smart, entertaining, and yes, funny way.

(Top Image via FOX; Screencap via my smartphone)

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Oct 28, 2015 06:17 pm