At age 10, I lost my mom to stage 4 pancreatic cancer after months of seeing her vomit from fever and treatment, virtually catatonic from pain, and verbally incoherent from morphine—after seeing her condition fall for the worse after a few weeks of having her home and seeing her actually being able to eat. I remember vividly how I didn’t cry that moment I was taken out of my fifth grade class, but rather bawled my eyes out the next day during a family dinner at a public restaurant, screaming how that—THAT—Was the worst day of my life.

Ten complicated, long years pass. I’ve moved out to college, and one day, I happen to hear about this game called That Dragon, Cancer, about two parents just trying to make a baby happy in a situation that would make anyone convulse in despair and frustration. Yeah, sure, I was intrigued, but I hadn’t truly expected it to speak to my personal experience on a core-shaking, visceral level. They’re kind of two different perspectives (parent v. child) and two different phases of life, after all.

Still, the more I thought about it, the more I realized I’ve never really explored any stories on loved ones surrounding the fighters. Let me expand on that statement: I had expected the game to resonate, of course, but I never anticipated just how important and—dare I mutter it?—healing it was, not just for those affected by disease or the loss of family, but for anyone trying to make sense of a life that’s been upended by tragedy and for anyone trying to understand a loved one who has transcended this mortal plane. All that comes with it. So, in the hope of reaching any of the many, many people whose lives are ravaged by such a beast, I come in an attempt to offer a little of my own perspective and interpretation on a very quiet, very special little game.

Living on the Edge of the World

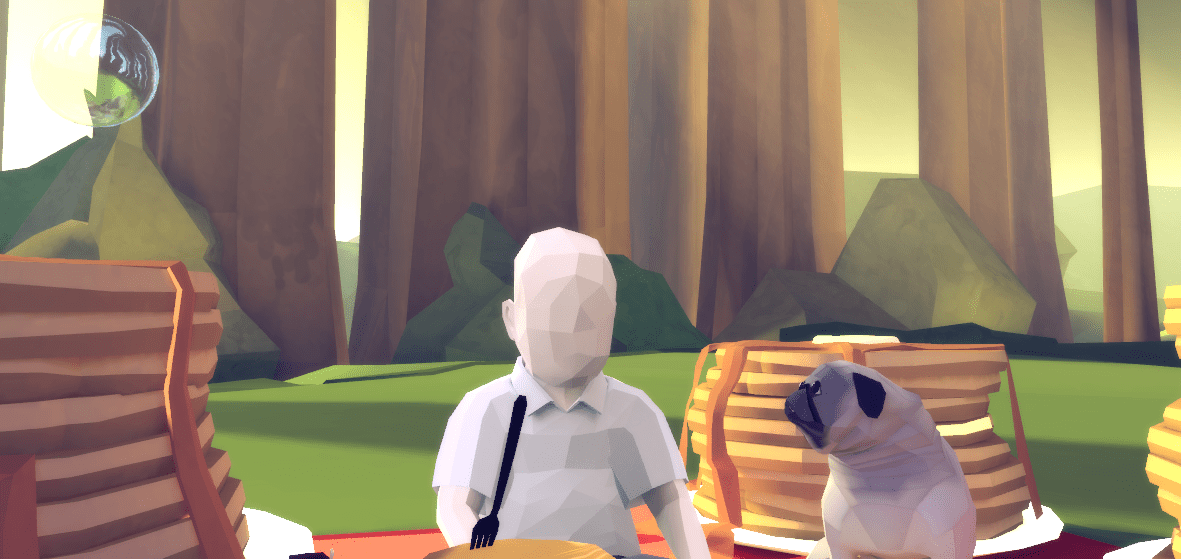

The narrative basics are as follows: That Dragon, Cancer is an abstract, autobiographical portrayal of the developers’ battle with helping their son, Joel, undergo terminal cancer treatment. The story takes place in two distinct settings, with each section taking place in either “relative” reality, which focuses more on the immediate, real-time toll of Joel’s treatment on “concrete” people and the park on the edge of the world. The park happens to include an endless mass of water filled with messages in bottles, memorializing various cancer victims (dead or not) and their families. The letters (as well as the ones that eventually show up in the hospital wing full of cards) themselves seem almost extra-diegetic; the narrator makes no comment on them. In fact, when you’re out to sea, you fly between and read each message as a seagull, and yet, the emotional resonance and overall message of being in a soup of other stories is absolutely felt all the way through.

In the game, the location itself is used to communicate not only the mother and father’s internal feelings towards … well, their baby suffering through a terminal illness in real time (the game was made before Joel’s passing), but also a place to do some processing. In one particular scene, the father questions his own place in Joel’s life, literally asking himself what his baby speak means (what Joel can possibly understand of what’s going on). This is reflective of the sheer inscrutability of having someone in your life who will not only leave for no discernible reason, but having that person transcend your understanding because of the simple fact that they’re not there any more.

Donning Your Own Armor

As the title says, cancer is a dragon, advancing relentlessly and cruelly with its burdensome body, gnashing its teeth for the moment to leave everything in ashes. It’s a tragic fight for anyone to have to endure, let alone a baby. It should also be said, I believe, that the ones being left behind are fighting their own, if different battles. In all honesty, losing someone is damn lonely, among many, many other things. Even with people around you being affected by the same thing, it can be difficult to understand their unique relationship to that person and their way of emotionally processing everything they may be going through. Part of the function of religion in the game is, in fact, to help the mother regain some semblance of understanding of the situation. That’s also part of the function of the game. Because with any sort of trauma, the topography of your life shifts and melds and turns upside down in all sorts of weird ways, and of course, it’s hard to keep from sinking when land is crumbling all around you.

After The Ashes

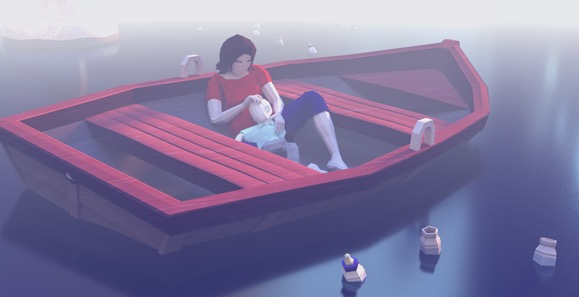

In the Big C universe, hope and despair seem to exist in a strange dichotomy where one can’t live with or without each other. During the earlier scenes, the joy of hearing Joel laugh and the surrounding love and support he gets fill his parents with hope and joy, only to have it come crashing down by the eventual reality of treatments. This is especially articulated in the aforementioned hallway of cards, where he races down the various memorials in a red wagon, hoping in vain that he could succeed them, only to have him crash brutally in the end. This is also seen in the opposing perspectives of the parents. While the father is shown as literally drowning by the island at the edge of the world, the is mother on a directionless boat without oars in rainy seas, desperately trying to keep her husband and baby afloat by her strength alone. In that moment, everything just seems … wretched.

Joel is destined to pass simply because medical advancement hasn’t progressed to the point where his disease, at that stage, can be cured under his conditions. His parents eventually come to realize that and are going through what turns into the exhausting process of trying to make peace with the fact that they can’t always protect him—that Joel has to fight this dragon with his own sword, despite all of the love and medical attention he’s receiving, even when the prognoses turns for the better. But still, there is hope. There’s hope because this game exists in itself, and anyone can experience loving Joel through his battle—a simple, atmospheric game with a beautiful score that turns into two parents memorializing a baby.

Because the hope isn’t about beating disease. Or trauma.

Because you absolutely can survive, despite everything.

Because it doesn’t matter how many times you need to break down to understand yourself, how many traumas you’ve gone through, what sort of various dysfunctions you have because you haven’t healed properly, how many boxes you put yourself in, or how long you have to flail among that endless lake of bottle messages. It’s OK to live. You are never alone.

(images via That Dragon, Cancer)

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Feb 20, 2016 11:00 am