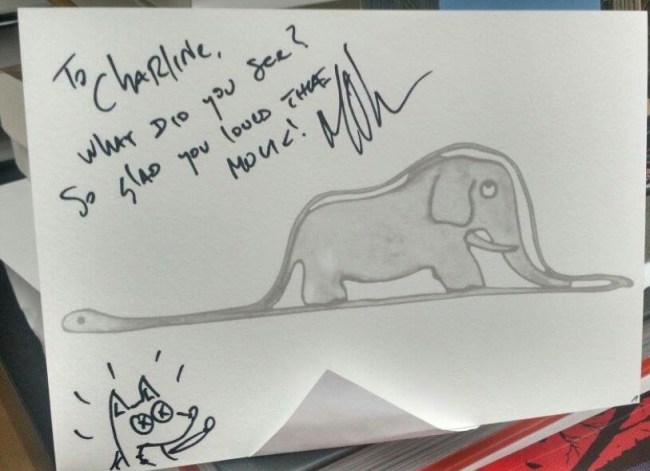

I had the opportunity to interview Academy award-nominated director Mark Osborne about The Little Prince, which comes out on Netflix today after a long wait. The movie, which uses a framing story around a little girl, is a touching and beautiful tribute to Saint-Exupéry’s work. Osborne and I talked about the pressure of adapting the story, the movie’s mixed-media approach, and what inspired him to put a young girl at the center of this film.

TMS (Charline): When you hear about something as iconic as The Little Prince being adapted, there’s two reactions. There’s the excitement of seeing something you love on-screen, and the hope of “Oh, I hope they get this right.” Were you conscious of that pressure?

Mark Osborne: Totally, from the very beginning. It’s one of the reasons I said no initially, because I don’t want to be the guy who screws up making a movie out of The Little Prince. The pressure was there constantly for everybody. So many people on the crew, there’s so much passion in the project because it’s really, you know, hundreds of people trying to protect the book as much as they can.

That’s why I think when I let people in on what I wanted to do, some people misinterpret it as, “You’re rewriting the book” and I go “No no no, the book is safe and it’s there and part of the movie and I’m writing a story around the book to protect it. To cradle it.” The book is there, intact, and I didn’t change a word of what I’m using from the book for my own purposes. All I’m doing is I’m taking pieces from the book and inspiring this larger story.

TMS: I’ve heard you refer to the movie as a tribute to the book, rather than just a straight-forward adaptation. What do you think is the power of that, or what does that mean to you?

Mark Osborne: Well, a straight-forward adaptation I think is necessary sometimes. I didn’t think there was any way to do it in this case, because the book lives in the imagination. You know, everybody who reads it has a different experience because you are affected by who gave you the book, if you’re thinking about someone else when you’re reading it—so everyone has their own experience and that’s why I said you can’t do this.

There’s no way to make a movie that is the book because the book is different for everybody. And that’s why the magic trick, the slight-of-hand I guess, is to say, “Well, I’m not going to do the book. I’m going to do her version of the book.” I’m going to give you the book through her eyes, and that’s how we protect that notion and mirror the way that the book works in our lives.

TMS: I think the power of focusing on certain characters is that there’s so many themes in The Little Prince, but by centering it around a young girl the themes of childhood and loss and growing up are really pushed to the forefront.

Mark Osborne: It gives you a focus, because everyone has their own lens. People say to me all the time, “You didn’t include The Lamplighter! My favorite thing!” and I said, that’s perfect because if you sat down with your friend—I’ve had this conversation with people and people don’t remember entire passages of The Little Prince. They forget about the Baobabs. They forget about this or that, because they focus in on the things that are meaningful to them and that draw them out. And that’s what I was saying: this is her version. If you’re upset that she’s not thinking about the Lamplighter, then that’s you having a conversation with your friend, “The Lamplighter means a lot to you? That’s great! And it wasn’t a blip on her radar.” I wanted the movie to be a conversation with a friend.

TMS: I’ve read the book at different points in my life, and I definitely latch on to different parts each time. I think something great about the book that carries over to the movie is that it’s really for anyone, and animation is so often thought of as a child’s medium.

Mark Osborne: Only here in the U.S!

TMS: Yeah! But it seems like there’s a shift in that, like, Anomalisa was a very serious film in stop-motion.

Mark Osborne: Sausage Party.

TMS: Oh my gosh, that’s definitely an adult animated film.

Mark Osborne: I was actually attached to direct Sausage Party.

TMS: Wait, really?

Mark Osborne: It’s crazy, I was developing both at the same time and I had to pick one or the other and I chose Little Prince.

TMS: Could not be two more different movies.

Mark Osborne: Nobody knows that. I was like, contractually involved. Actually, I saw a funny quote yesterday that said “Sausage Party and Little Prince (that’s the first and last time those two will be mentioned in the same sentence)” and I was like—

TMS: You were wrong.

Mark Osborne: There’s a story. But I love animation for its ability to tell stories in ways that you can’t in live-action. And I think animation has as much potential, and in some cases, more potential than live-action. So, I’m super excited about anything that breaks the mold and goes in a different direction. That’s precisely why I was involved in Sausage Party, cause I was like, “This is going to change things.”

Anybody that works in animation loves the idea of being able to work on an R-rated movie, grown-up themes, and Anomalisa, I thought, was incredible. I was just so excited to see it, I couldn’t believe it existed. It’s a fantasy of what Charlie Kauffman could come up with as an animated movie.

So, for me, this movie presented an opportunity to do something that was, you know—I didn’t want to make something that was just for kids. The book is so cleverly written to the child inside of every grown-up. It’s not a kids book, it’s a book for grown-ups to get in touch with your childhood. So, I thought, that’s what I wanted the movie to do, to transport grownups back to their childhoods, give kids something they could experience and ask questions about, because that’s how I think the book works. You read it to your kids and they go, “This is weird,” and then you have a conversation. That’s so important.

I wanted the movie to have the same emotional experience. I wanted it to be parallel, but I also wanted it to start conversations—between parents, between families, between people that are in relationships.

TMS: I know you consciously made the choice to make the main character a young girl because of the Geena Davis study. Also, when you referenced Miyazaki in an interview that clicked for me a lot too.

Mark Osborne: I love Miyazaki, it’s sort of a perfect storm. I have a daughter, we’ve seen Mulan a thousand times, we’ve watched every Miyazaki film and to me, I wanted to put good examples in front of her and they were hard to come by. And in big Hollywood movies, it’s mostly princesses. For me, Miyazaki is an inspiration not only for his imagination and creating fantasy worlds that blend in with reality, but Totoro is the tonal example. I would say “I want this to feel like Totoro.”

But what happened after I made Kung Fu Panda was I got invited to participate in the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media‘s study, and that study opened my eyes because I thought I was participating as the person that just made Kung Fu Panda and strong female characters—but every other character is a man. And there’s only two women! They laid out all the statistic, especially related to animation, and it blew my mind.

And I went back, and the book was sitting on my table and I was thinking about what kind of movie I’d make. I looked at the book really closely and there’s one female character: the Rose. There’s a gender imbalance in the source material, what am I going to do? So, I think it was those things that fit together and, look, if I’m going to tell the story of a little boy reading a book about a little boy, like, that’s kind of problematic. It’s fine, but it’s just not balanced.

The little girl is really an opposite to the Little Prince. She’s little—that’s the only thing they have in common. She’s a grown up. And so, that sort of started me on this road. I really like the idea of creating this little girl character who can be this broken grown-up and, in some ways, an echo of the Aviator. The Aviator is broken when he meets the Little Prince, and the girl is broken when she meets the old Aviator. So, I’m telling a parallel story that is echoing the book.

If I hadn’t participated in that study—and I give them a lot of credit for it, for being very very much presenting the problem. The problem’s never going to change unless we’re aware of it and I was—I couldn’t believe how unaware I was. Even as the father of a daughter who was thinking about this stuff.

TMS: So the voices from the book, the way people talk in the book is very different from how people talk in the CG-world of the movie. Was it difficult to navigate those different tones not just visually and in sound, but overall?

Mark Osborne: Yeah, very very hard. Balancing all the elements—we were constantly saying, “We want to push the envelope but we don’t want to go too hard.” We needed to create this grown-up world that was poisonous, and the antidote is the story and imagination. The antidote is being able to think like a child, the escape into this world where it’s poetic. It’s beautiful, like, we had to play a lot with contrast, but the words of Saint-Exupéry are hard to say. I mean, James Franco, luckily he was in love with the idea and is very literate, and very smart, and he understood the weight of it—but it’s very hard to say. It’s poetry.

So, the world we were trying to build around it was to contrast that poetry, but we wanted the whole thing to feel like it was consistent and of the same universe. People don’t say this too often, like, “you made a sequel.” And, no no no, you can look at it that way, but it’s reductive. I say we’ve extended the storyline just as a means to an end to be able to underscore the book.

TMS: I will say that at the end when the rose isn’t just dead but it also crumbled into dust I was alone in my room and I just gasped. It was a very devastating moment, but also a learning moment.

Mark Osborne: Well, for her in particular, and when people are too broken up about it I whisper them the secret which is, “It’s in her imagination.” It’s her dealing with the idea of losing the aviator and even the way people sort of, the way her relationship is with her mom. I mean, spoiler-alert like crazy but the mom, people go, “How can the mom change?” and I think the mom had a sleepless night and thought, “If I were taken to the hospital would my daughter ride through the rain desperate to be by my bedside?” and she had to realize “I don’t think so.” There’s something that’s happening between her and the aviator that I don’t understand and she’s given a gift at the end, which is the entrance into that world.

Mark Osborne: There’s definitely stuff in the movie where, if you’re a die hard fan of the book, it’s hard and, in some ways, a little bit punishing. But some of those things, it has to be cinematic. It has to have stakes. I try not to say exactly what those twists are, but this is a little girl’s adventure to understand this book and to understand her own deepest fears and anxieties about growing up.

TMS: Shifting to the Little Prince, I felt like there was so much love for Saint-Exupéry’s original illustrations in those scenes. The paper, the watercolor tones…What do you think it is about stop-motion that really brought that spirit out in a way that CG might not be able to do?

Mark Osborne: It would have taken ten times as much money and time to force CG to be as organic as you can be instantly, I mean, I say instantly but only with really super-talented artists can we achieve these kind of results. There’s an organic, sort of flawed, artistic detail that’s really hard with CG. Stop-motion, I love it because when you’re watching it, it’s magic. It is magic, and for that reason alone it’s the perfect way to express the passage. It is, like, you feel like your brain knows these things were made by somebody and moved by somebody—and yet they’re alive. This is wonderful.

TMS: I saw the behind-the-scenes footage of the detail and craft that went into it. It’s amazing because his illustrations are so simple, but they elicit so much emotion.

Mark Osborne: That’s great! One of the things that’s happening in the book that’s so genius is he says, “Here’s my drawing. It’s not very good, I’m not an artist, this isn’t what he really looked like…” The aviator is kind of tricking you into thinking about him as real and the idea was that she tries to think of him as real, and this is as far as she gets—that idea that this is like a craft project in her brain. It’s just very innocent and child-like.

To build everything it all out of paper was the genius thing that Jamie Caliri, my co-director on these sequences, brought. He brought the experience and the know-how for us to be able to use paper to do everything. So everything you’re seeing in those frames, anything that’s catching light, is paper. It’s one of things I think is significant, because it ties us back to the book—back to the pages. It’s an emotional connection.

TMS: And there’s a really interesting use of 2D as well.

Mark Osborne: Yeah, actually we used four different techniques. People go, “How do you use two techniques?” We used four! But the drawing was a way to kind of ease people into the movie, and then give them surprises throughout.

TMS: What character do you connect with most, in the book or the movie?

Mark Osborne: I guess the fox. I mean, just that wisdom is so profound. What’s crazy is that the best wisdom the Little Prince has comes from him. He’s a very important character.

TMS: I also love that the girl has a stuffed plush version of the fox.

Mark Osborne: Yeah, it makes her look like a kid. But I love the Aviator. I think I really related a lot. I was 20 when I first read the book, and I really related to that sort of zone he’s in at the beginning—finding himself as an artist because that’s what I was doing at that age.

The Little Prince is a movie with a lot of love for Saint-Exupéry and I think both fans of the book and people who’ve never read it will have a great time. I definitely recommending giving it a watch!

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Published: Aug 5, 2016 01:01 pm