My friend and I often talk about our dreams together. It’s not so much “dreams” as goals or ambitions but rather the experiences that run through your head while you’re sleeping. She once described a dream to me where she said she had this sense that the world was ending and she was running all throughout her home trying to find the things that were important to her, the things that mattered. Often, my own dreams revolve around the idea of running or being chased, and to hear someone else’s take on the “desperate, reaching”-feeling dream was striking, to say the least.

It’s with this in mind that I entered Tacoma, the newest offering from Fullbright, the creators behind the critically-acclaimed Gone Home. Players take on the role of Amy, a subcontractor for a large corporation in space, sent to essentially salvage what remains of the abandoned space station Tacoma, in orbit over Earth. Independent of this objective (really, the only objective), players are also offered the opportunity to uncover what happened on Tacoma in the days before it was abandoned. Entering different rooms triggers a notification from the in-game alternate reality device, which informs you that there are AR recording remnants that you can play through as you wander through the room.

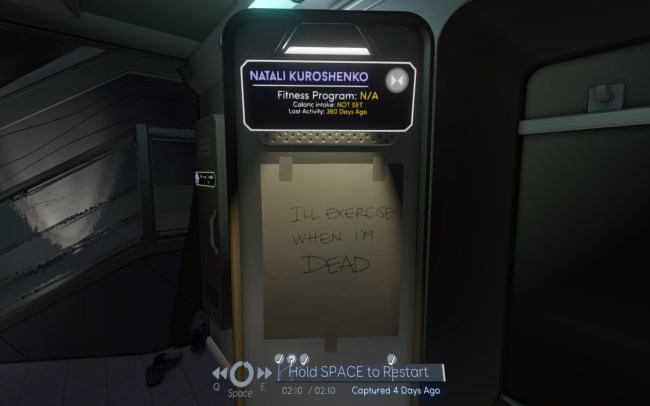

Much of the game is made up of you watching these scenes—literally memories—play out around you. The small crew of the Tacoma are only represented by six different wireframe figures fleshed out by some bright colors, a bit of a contrast to the rest of the station, which, in the absence of the installed creature comforts, screams corporate efficiency. You get a sense of what each of the crew members looks like thanks to a crew roster and ID photos (for the most part), but other than that, you only get figures.

I remember thinking that they’re a bit like ghosts in this way, and as I wandered (or floated) through Tacoma’s halls, I wondered if perhaps that would prove to be a bit of a prescient thought.

Not too far into the game, you learn that disaster has struck the Tacoma, and suddenly the crew are gathered in a desperate plan to escape the station. So suddenly, much like that dream my friend described, everybody has to decide what matters most to them; what do they have worth saving, and what’s better off being left behind. Again, as a salvager wandering around the remnants of an abandoned space station, you’re literally wandering around the things that were left behind, only here, alongside precious photos and small mementos are the actual ghosts of real memories.

At first, I spent a lot of time in Tacoma trying to piece together a full, complete story of what happened. I was totally that nerd scanning every QR code in the game (believe me, there are a bunch) because dammit, I was going to figure out what happened come hell or high water. But the thing is, that’s not really what mattered, in the end. Eventually, the central “plot” of the game fell away, and I was utterly absorbed with just wanting to learn about these characters. This isn’t only a testament to the game’s writing (which I thought was stellar, no pun intended), but also its storytelling mechanic.

There was a certain kind of strangely cinematic quality to having this power where you can wander about and replay conversations and interactions at your own discretion. In the back of my mind, I knew that I was watching what amounted to a video recording, but it never once felt like that, even as I scrubbed back and forth listening to somebody, say, profess their love for another, or admit that they’re afraid for what might happen in the very near future. There was a poignancy to wandering around and experiencing this growing, unfolding story, knowing that I, as a character, was already wandering around a space station devoid of life.

After a time, I didn’t think of these recordings as the incorporeal, intangible ghosts—no, it was I who haunted the station here. Despite knowing full well that my character was standing there, amidst simple recordings, I felt invisible, blended into the background of a story that I’ll never, ever directly impact. And that powerlessness, that knowledge that everything I’m watching has already come to pass? That was what weighed heaviest on my heart as I wandered through Tacoma’s halls, at once empty and yet so vibrant and full of life. An uneasy sense of dread that had planted itself in my stomach right at the beginning of the game slowly blossomed into something much larger, much more sinister as the story unfolded. Pleading questions ran through my mind as I played: What can I do? How can I help? Please, just tell me.

They all went unanswered, of course.

Instead, all I could do was watch and sift through the things they left behind. The best I could do for any of the Tacoma crew was to listen to their story and do my best to honor their memory, fleeting though it might be.

As a game, Tacoma left me with so many more motivations than it did emotions, per se. It conjured up this desire to think about the things I’m likely to leave behind if ever I should, well, leave. I thought about the memories and the experiences I’ve shared with people and wondered if any of those would ever be thought of as stories good enough to pass on—I wondered … I wondered if I was good enough to be remembered.

As the game came to a close and the credits began to roll, I remembered a quote from Adam Gnade’s The Do-It-Yourself Guide to Fighting the Big Motherfuckin’ Sad. It goes:

“You can be a hermit and you can be an island, but when the paint gets stripped away, we are what we build up around us. We are the sum of our actions, our chosen environment, our loves, our pleasures. So, count on your friends. Have faith in your friends. Never let them forget that sometimes—in the worst, darkest, most fucked moments when the whole gale is howling around you—they are what keeps you here—alive and fighting. Your friends will be your ballast. Your friends will sing your story when there’s no one left to know the tune. Fuck those who aren’t worth a damn; your true friend are the answer you’re looking for. Your friends will carry you home.”

In our darkest, scariest moments, when the world around you is coming to an end, the only things we can truly hold on to are our friends, our families, and our loved ones. Tacoma reminds us of this fact, and it does so in such a powerful, important way that I know I’ll not soon forget.

(images: screengrabs)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Aug 4, 2017 05:36 pm