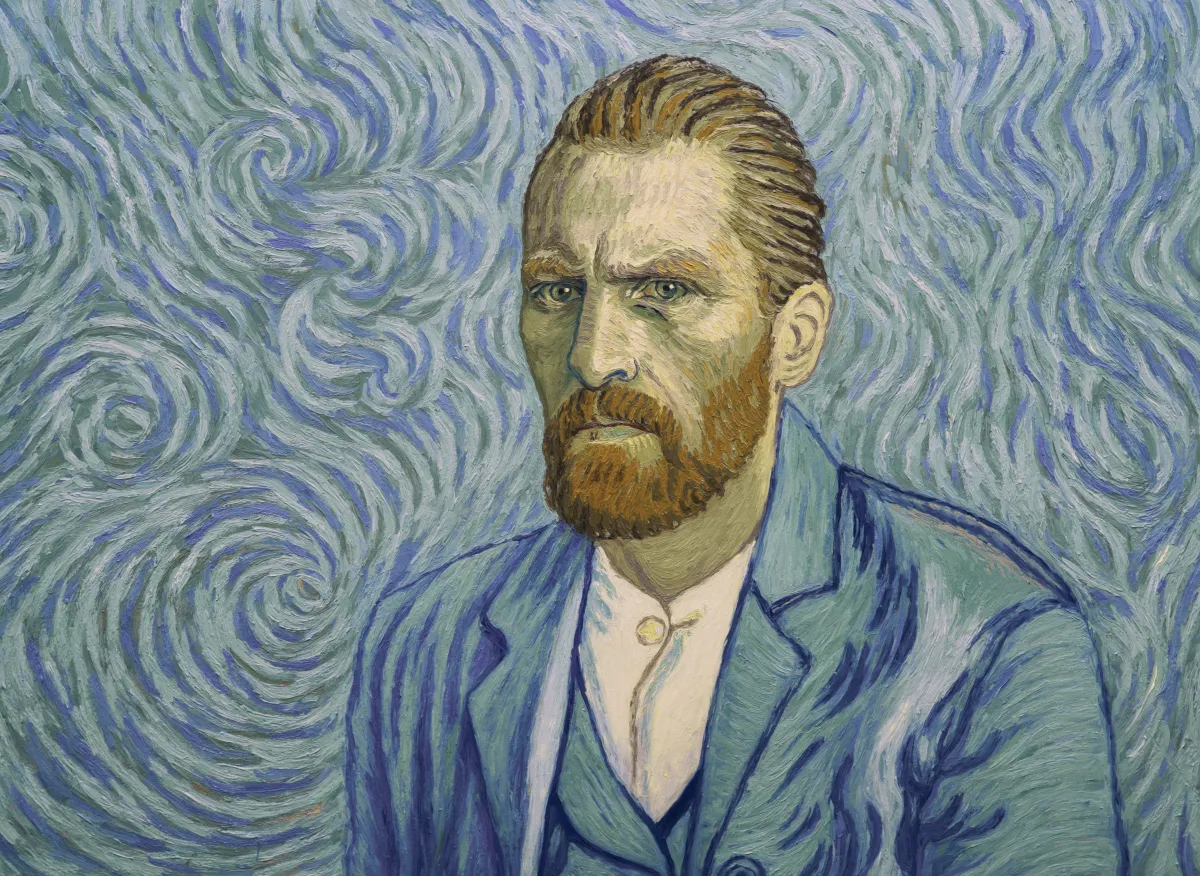

Over almost a decade, writer-directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, along with 125 painters, produced 62,450 oil paintings that became Loving Vincent.

There are two stories told within the film, separated jarringly by black and white scenes and scenes told through the artist’s vivd impressionist style. These shifts transport us through time—events leading up to the death of van Gogh are in B&W, and events in the “present” are in color. The story follows episodes of van Gogh’s life through the perspective of Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth) who must deliver a letter to the artist’s brother Theo van Gogh. It’s a task he somewhat begrudgingly takes on after his father (Joseph Roulin, van Gogh’s postman) emphasizes the important of van Gogh’s final letter finding a recipient.

After Roulin discovers that Theo is also dead, he goes on a journey to deliver it to van Gogh’s doctor Gachet whom he believes is the most suitable recipient. The story then becomes a kind of pseudo-crime mystery as Roulin talks to various people who knew the artist. Gauguin, a fisherman, the doctor’s daughter, the woman who ran the inn he stayed at, his paint supplier, etc. all share memories of the artist. We learn that van Gogh went from perfectly happy to allegedly suicidal in six weeks—or did he? Was he murdered and instead lied about the cause?

This mystery plot, it turns out, serves more as an excuse to speak to different people involved with van Gogh than anything else. Through this we see van Gogh the genius artist, van Gogh the tortured and deeply lonely soul, van Gogh the awkward man, etc.

The artwork is mesmerizing, as if we are watching a painting organically move and take on a life of its own. The frame often lingers on van Gogh’s original composition before going into motion, which feels like an excellent and appropriate tribute to his work. There is nothing else like it. However, the films shines best in its quiet moments and in specific sequences. As a complete piece, the art can sometimes feel almost too rotoscope-y and during transitions, things get almost overly punctuated by individual paintings.

Of course, the biggest appeal of Loving Vincent isn’t the story but the art. Still, the two don’t complement each other or fit together as seamlessly as they should. This stiff pacing, as well as the back-and-forth between investigation and biopic conventions, makes it difficult to stay immersed at times. I suspect that this might be the great challenge of the film, to try and capture the magic of van Gogh’s paintings and build on them in a different medium. When we think of the wonder that a van Gogh painting inspires, the story told here just feels a bit … underwhelming. And while one cannot deny the talents of Saorise Ronan, Chris O’Dowd, and Jerome Flynn, this feels like a film where casting less recognizable actors would’ve been a better choice.

Despite the stumbles in story, Loving Vincent provides a small glimpse into the mind of this genius man. It likely says more about him than the film, that the movie couldn’t fully contain his capacity for love, loneliness, and imagination. Instead, the film chooses instead to observe the impacts he had on the people who knew him and the impact he still has on us today. While those already familiar with the artist might not gain too much from the story, the beauty of the film is sure to be a treat for fans of van Gogh’s art and history fans.

The title Loving Vincent is a reference to the artist’s signature and how he ended his letters, “Your Loving Vincent.” However, it clearly has a secondary and third meaning—that this is a film about the people who loved Vincent van Gogh and grieved his death, as well as the people who still love him today. The film is a clear labor of love.

Especially for a figure that’s so often romanticized for his mental illness and deep sadness, it’s a beautiful way to remember the love that surrounded him and the love he put into the world.

The shifts in color, while occasionally disjointed, show how the van Gogh saw the beauty in the most mundane, forgettable, and bland spaces. Places, object, and people that would have been forgotten became vivid, unforgettable masterpieces unlike anything else. For me, these images—more than any dialogue—emphasize what kind of vision, talent, and character was lost when van Gogh died.

(images: Good Deed Entertainment)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Sep 25, 2017 10:17 am