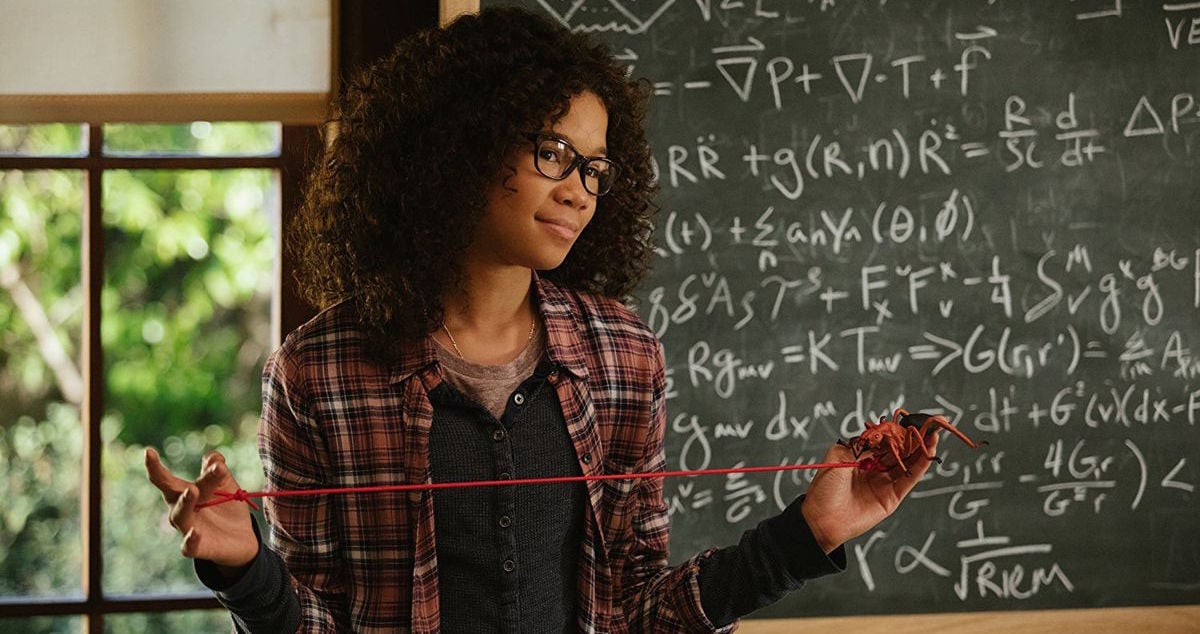

The response to Ava DuVernay’s A Wrinkle in Time has been starkly divided. The reaction seems to come down to whether or not the movie, brimming over with earnestness, spoke to you on a personal, intimate level. Those who are praising it are, largely, not talking about the filmmaking or the storytelling; they’re in it for the emotional resonance and the personal connection. A lot of people simply didn’t feel that connection, and that’s fine. I did, mostly because I kept thinking how much the movie would have meant to me if it had existed when I was nine or ten, the age when I read Madeleine L’Engle’s book.

As it did for so many others, A Wrinkle in Time meant the world to me. I hadn’t read it in multiple decades, so a few months back, I revisited the book. I gave it enough time to settle into my chronically terrible memory, so I didn’t go in with dozens of “but what about this part!?” comparisons at the forefront of my mind. Even so, the changes the film made were striking. Some made total sense in adapting what has long been called an “unfilmable book.” Others were, I’m sure, just as necessary, but left me feeling like something important was missing.

Let’s break down some of the biggest changes from the novel. Maybe we can flesh out some of the reasons why not everyone felt the same connection with the film as they did with the book. (Spoilers for both the book and the movie ahead!)

The Murrays

The specifics of the Murray family were very different from the book. Meg’s twin brothers were cut entirely, presumably so as not to overcrowd the focus on Meg and Charles Wallace. However, DuVernay has pointed out that if sequels move forward in keeping with the book series, which focuses heavily on the twins, the Murrays are already established as “a wonderful family who adopts children.” So perhaps there’s room for this family to grow.

The casting of Meg as a mixed-race girl (as well as the diversity of the Mrs. and the casting of Charles Wallace as an adopted son) was a divergence from the book and obviously, there were always going to be plenty of racist trolls who would see this as a drawback. But we’re not here for them and their terrible opinions. For so many readers, Meg was the first time we saw a protagonist like her: a young girl whose brilliant mind–the thing that makes her an outsider with her peers–ends up being the source of her heroism. In what DuVernay has called her “love letter” to black girls, it puts young black girls at the center of that representation. Meg’s journey of self-acceptance felt so personal and so intimately specific that this change only enhanced the story.

Meg

The part of Meg that is hard to put on a screen is her brilliance. Yes, we know Meg is smart—a genius—but could the movie capture just how special her mind is? In painting her as an outcast among her peers, it felt, to me, to be fairly normal mean girl activity, rather than the story of a girl whose mind is so unique that she just cannot relate to other humans. And if we can’t grasp the level on which Meg’s mind operates, how can we comprehend Charles Wallace, who, in the book, can read his sister’s thoughts at times, and who can “understand the wind talking with the trees”?

Did you get the feeling that Film Charles Wallace’s mind operated on a different plane? Or that he was merely especially brilliant?

The Mrs.

The depiction of the three Mrs. was always going to be different from the book, as so much of what defines their characters is–like Charles Wallace–their indescribability. Many of the changes made to the three women are superficial: their outfits, or Mrs. Who’s use of modern quotes. (Though I admit I was not emotionally prepared to hear her quote Hamilton.) But in the book, Calvin describes the three as “guardian angels” and “messengers of God.” In fact, there are a lot of mentions of God in the novel. Which brings us to another big change …

Religion

When thinking about how much I loved this book as a child, I have no recollection whatsoever of noticing the religious elements. But on reread, it was pretty apparent. It’s no Chronicles of Narnia, but Meg is told she was called to her current purpose by God, Bible verses are used as inspiration, and the whole good vs. evil battle was pretty firmly rooted in Christian context.

I’m all for leaving religion out of children’s entertainment, but in this case, it didn’t seem to be replaced with anything, leaving everything—from what the Mrs. are and why they’re here, to the nature of the evil the characters are fighting—lacking a specificity it could have used.

Speaking of …

The IT & The Darkness

The immediate difference between book IT & movie IT is its appearance, with the former appearing as a giant brain, and the latter a creepy mass of dark tendrils. But that seems inconsequential. Well, sort of. We’ll come back to that.

In the movie, the darkness our heroes are fighting is responsible for negative emotions on Earth. It’s why the mean girl next door lashes out at Meg and why, as we learn, that neighbor struggles with her own self-esteem and possible food disorders. It’s why Calvin’s father is cruel to him. It’s the source of people’s destructive behavior.

In the book, the power of the Black Thing is kept fairly vague, and that’s what makes it so terrifying. It’s an all-consuming shadow, and a “horrifying void.” And, like so much in the books, it’s nearly indescribable except in how it makes characters feel, which is completely devoid of hope. The darkness was my first understanding of deep sorrow and depression. The movie’s IT looks scary, but the book’s Black Thing chilled me in a way I’d never experienced.

Aunt Beast and everything after

In the movie, when Mr. Murray is trying to tesser without Charles Wallace, who is still under the control of the IT, Meg stops him. In the novel, he’s successful, and he, Meg, and Calvin regroup on a planet called Ixchel. There, Meg is tended to by a creature called Aunt Beast. (She also has to try to explain “the Darkness” to a species with no visible sight, which goes a long way to help the readers understand how powerful that force is.)

Jennifer Lee, who wrote the screenplay, has spoken about the film’s omission of Aunt Beast, and her explanation makes total sense. As she says, “Aunt Beast was a part of the book that provided support, but she also provided the answer. This was a journey we reworked, where no one is gonna give Meg the answer. She has to find it herself.” Plus, it probably keeps from adding another 20 minutes to the runtime.

But once again, in removing the book’s narrative, its replacement feels muddled.

First, while I understand Mr. Murray’s desire to hurry the hell out of this place that was his prison for four years, his willingness to leave Charles Wallace felt callous. In the book, we get to see him keep his word and return for his son. In the movie, it’s hard not to share Meg’s disbelief that this will be possible, meaning we have to believe Mr. Murray is ready to abandon his son.

In both the book and the film, it’s Meg’s love that saves Charles Wallace. In the original, she’s told that she has one weapon with which to fight the IT, and it’s something it doesn’t have. The fact that her weapon ends up being love fits into a larger, seemingly paradoxical message of the book: that this world clearly values intellectualism, but that pure intellect is also the villain. Mindless intelligence is what the heroes are constantly fighting against: Charles Wallace gets hypnotized by monotone recitation of times tables because that act is so far beneath the capacity of his brilliance; in the book, Meg is thought of as a slow learner by her teachers because they make her do her math problems “the long way around,” and she just wants to let her mind run ahead. There is a huge difference between a brain (as the IT was originally depicted) and what a person can do with it.

The book celebrates free thought, creativity, and an intelligence that surpasses language. The film celebrated love. And while that is a wonderful message, I found myself missing the complexity of the book’s vision.

What about all of you? What did you miss (or not miss) from the book? Were there changes that you liked? Tell us your thoughts!

(image: Disney)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Mar 15, 2018 01:40 pm