Today is the 80th anniversary of Executive Order (E.O.) 9066, in which then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt authorized the evacuation of “persons deemed a threat to national security.” After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. government used executive action to forcibly remove those of Japanese heritage from the West Coast of the country. The military uprooted tens of thousands of Japanese Americans from their homes and sent them into concentration camps (as far east as Arkansas) for years. The day is now recognized as the Day Of Remembrance Of Japanese American Incarceration During World War II.

In addition to the 100,000+ Japanese Americans, the U.S. government sent East Asian Americans, Native Americans and Latin Americans (with heritage from an Axis country) to these camps. This action, and the fact that the Supreme Court (Korematsu v. the U.S.) sided with the state, continue to haunt many Americans today through racist, xenophobic E.O.s like the Muslim Travel Ban and more.

In observance of this day, we want to share some books that reflect on the lives of those who were in those prison camps. There are memoirs, biographical narratives, and one or two works of fiction from the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those incarcerated during WWII.

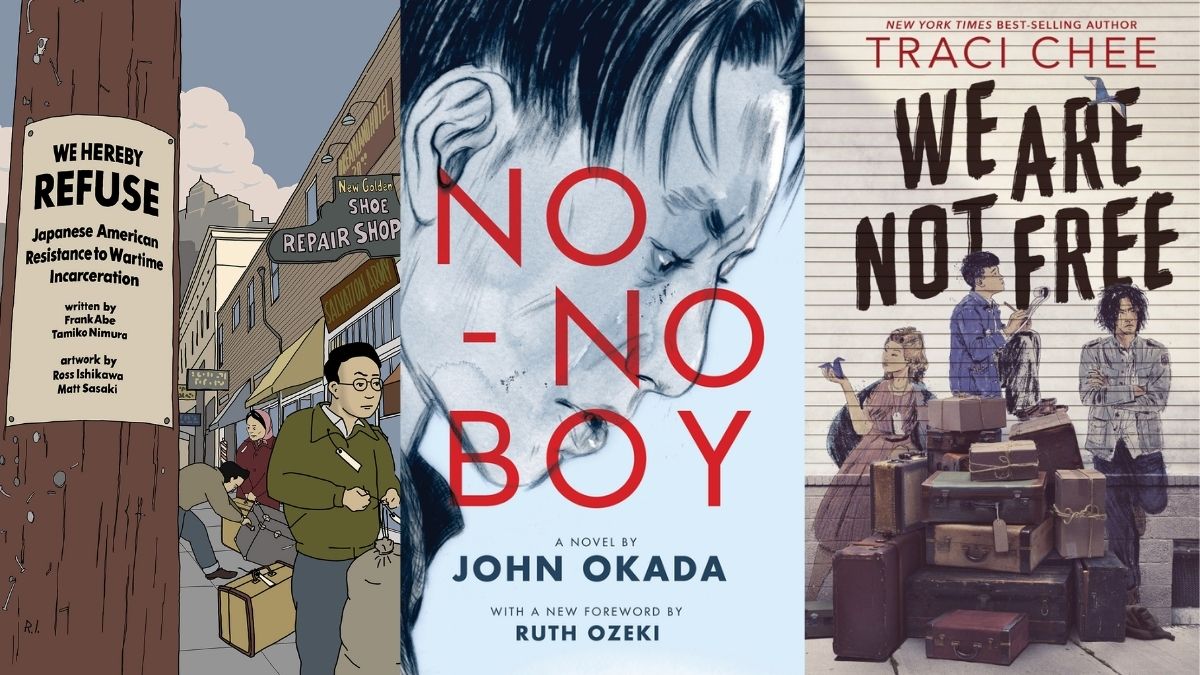

No-No Boy by John Okada

(University of Washington Press)

Initially published in 1957, Okada’s No-No Boy is widely considered one of the first novels to detail the experiences of Japanese internment by someone who lived it. He tells the fictional story of Ichiro Yamada, who chose “no-no”, thus declining to serve in the U.S. military during WWII, and the fall out from his community after.

“No-no” is an epithet for those who selected “no” for questions 27 and 28 of the required loyalty questionnaire. Some camps segregated the “no-no”s and revoked citizenship (regardless of the country they were born in.) The questions were:

- Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

- Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attacks by foreign and domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or disobedience to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?

At odds with many Issei (first generation of Japanese Americans who were middle-aged or older during WWII) both in the camps and after, many Japanese Americans (and publishing at large) disregarded Okada’s novel for decades.

We Are Not Free by Tracie Chee

(Clarion Books)

Chee’s historical fiction Y.A. novel follows a tight-knit group of friends from Japantown, San Francisco, who experienced those uprooted years together. The four friends try to stay true to themselves among conflict within their families and the country where they grew up. As teenage Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans), they felt especially resistant and vulnerable to the unjust actions of the U.S. government.

In 2021, The National Book Award shortlisted We Are Not Free in the Young People’s Literature category.

They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, and Seven Scott

(Top Shelf Productions)

George Takei’s (of Star Trek fame) graphic memoir shares his experience growing up in the camps as a child. Only five years old at the time of the E.O., he didn’t fully understand what was going on. Because his parents were trying to protect him, Takei’s imagination (and lies from older kids) shaped his perception for a while. Later moments of the graphic novel show Takei processing this event of his childhood as an adult and the path to reparations.

If your looking for a fictional title, another one that reads very well is Displacement by Kiki Hughes. Inspired by Octavia Butler, teenager Kiku finds herself traveling back in time where she witnesses her grandmother’s internment and learns how those years changed her grandmother’s life forever.

Looking Like the Enemy: My Story of Imprisonment in Japanese American Internment Camps by Mary Matsuda Gruenewald

(NewSage Press)

At the age of 16, the author and her family decided to collect and burn all of their Japanese possessions after hearing about FBI searches following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Two months later, the government uprooted her family from their 10-acre farm in Vashon Island, Washington and sent them to the Midwest.

For decades, Gruenewald, like many Japanese Americans who remembered the camps, stayed silent about her experience. This silence came from shame, the instinct to bury the pain, and the need to assimilate for survival when they left the camps. In 2005 upon her eighties, Gruenewald finally spoke up about the psychological effects of living in the concentration camps.

We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration by Frank Abe & Tamiko Nimura, artwork by Ross Ishikawa & Matt Sasaki

(Chin Music)

In many of the darkest parts of American history, there is this false narrative that nobody resisted or that these acts of violence were a choice. Almost all of these books touch on this. However, We Hereby Refuse centers on the resistance of three Japanese Americans interned during WWII and includes narratives about more “no-no”s.

Weaving together these three narratives, this graphic novel looks at the small and large ways some defied this unjust system. Not just the act of being put in the guarded camps, but also the loyalty oaths and forced deployment of some to fight for the U.S. while their families remained in these camps stripped of their civil liberties.

Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment by Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro

(W. W. Norton & Company)

If Dorothea Lange sounds familiar, it’s because she is the photojournalist known for capturing the millions of lives upended by The Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. Her other significant contribution to American history was documenting the tens of thousands of Japanese Americans forced to travel to the Midwest.

Lange’s photos capture the uncertainty of the families and the many unknowns regarding their future. The public saw almost no pictures of the camps until after the war, and the federal government censored most of the 119 photos in this book for decades.

(images: Chin Music, University of Washington Press, and Clarion Books.)

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Feb 19, 2022 03:47 pm