***Spoilers ahead for the third episode of The Last of Us and some character information from the videogames. Be warned.***

The Last of Us pulled the biggest switcheroo on us all with its third episode—tricking us into clicking play on what was supposed to be yet another hour of the post-apocalyptic, zombie-riddled adventures of unwilling father-daughter duo Ellie and Joel and instead running us over with one of the most beautiful and heart-wrenching queer love stories ever put to screen. When I tell you that I was sobbing so hard by the end of it that I couldn’t see my screen, I’m not exaggerating.

The episode might have gotten review-bombed by you-know-exactly-what-type-of-fan because of course it did—how shocking, really, to see two gay men finding love and companionship in a world where a lesbian teenager is the physical embodiment of hope—but the general critic consensus on it has been favourable and filled with praise.

There are, of course, a myriad of factors that have worked to make “Long, Long Time” one of the most excellent hours of television we’ve all had the pleasure to witness—starting with the performances of Nick Offerman and Murray Bartlett, who play Bill and Frank respectively. But before we all continue following Ellie and Joel on their journey during the upcoming Episode 4, I would like to highlight another one of them.

It’s the fact that the story of Bill and Frank is both queer text and queer subtext—and that it’s these two elements working together that help make what we saw in “Long, Long Time” so incredibly powerful.

On the one hand, there’s the queer text: the romance that plays out in no uncertain terms from the moment that Frank falls into one of the traps that Bill has set outside the perimeter of his town. If you’re not familiar with the source material of The Last of Us, you might have been picking up on some vibes throughout the first meal the two share together—but it all becomes pretty clear as soon as the action moves to the piano. That’s all text. Something that the media is explicitly telling its audience and that can’t be mistaken for anything else.

On the other, there’s the subtext, the core of queer storytelling for years, when you couldn’t exactly have openly queer characters in films and television shows. Maybe because it has been such an integral part of this type of story for such a long time, it still is one of its cornerstones now that we can actually see queer romances play out on the screen.

The subtext is in the lingering looks, in the hands, in the double entendre of sentences and situations, and in the metaphors. When it comes to Bill and Frank, their queer subtext is in the strawberries that they grow together, in the flowers that Bill waters even as Frank’s physical condition worsens, in the song that gives the episode its title. It’s in the great metaphor that is their situation—two older gay men, one of whom had definitely given up hope of finding love and companionship and thought that retiring from society was his only option. Despite everything, they manage to make a home together in a world that is quite literally out to get them.

It’s a beautiful undercurrent that enriches their story and really makes it work. Because sure, that could have been a heterosexual couple. But the fact that such an important message—both in-universe, since it’s what ultimately drives Joel to really accept his “mission” and bring Ellie wherever she needs to go, and outside, as we the audience get another chance to reflect on what living and surviving really mean—was instead entrusted to a queer couple has a meaning. This meaning can be found when putting the text and the subtext together.

As I was chatting about the episode—meaning wailing through long audio notes—with my best friend, we realised that it’s similar to what Our Flag Means Death has done. The show is undoubtedly a queer romance, and there’s no mistaking it from pretty much the moment Edward “Blackbeard” Teach and Stede Bonnet meet each other on the bridge of the Revenge—and it continues to be a romance all the way to its last episode.

Yet just because its love story is told in very clear beats, it doesn’t do away with all the subtext that makes fandoms thrum to life and create all the beautiful pieces of meta, fan art, and fanfiction you can imagine. You could write a dissertation on the imagery of the kraken and the lighthouse alone, or on how piracy in media has always been a metaphor for freedom for those “othered” by society. Actual Best Television Show Ever Created Don’t Fight Me On This I Will Win™ Black Sails did the same thing—just, you know, with a lot more violence and gore than Our Flag Means Death.

Of course, you can have a queer story with just the text or with just the subtext— there have been plenty of both and there will continue to be. However, something with just queer text will sometimes risk falling flat, while queer subtext alone allows creators and producers to still hide behind saying that “it was never explicitly said they were queer so if you read it that way it’s all you” and some good old-fashioned queerbaiting.

“Long, Long Time” just proved once more that to make the truly great stories, the ones that leave you sobbing and to which you will keep on returning and returning, you really do need both.

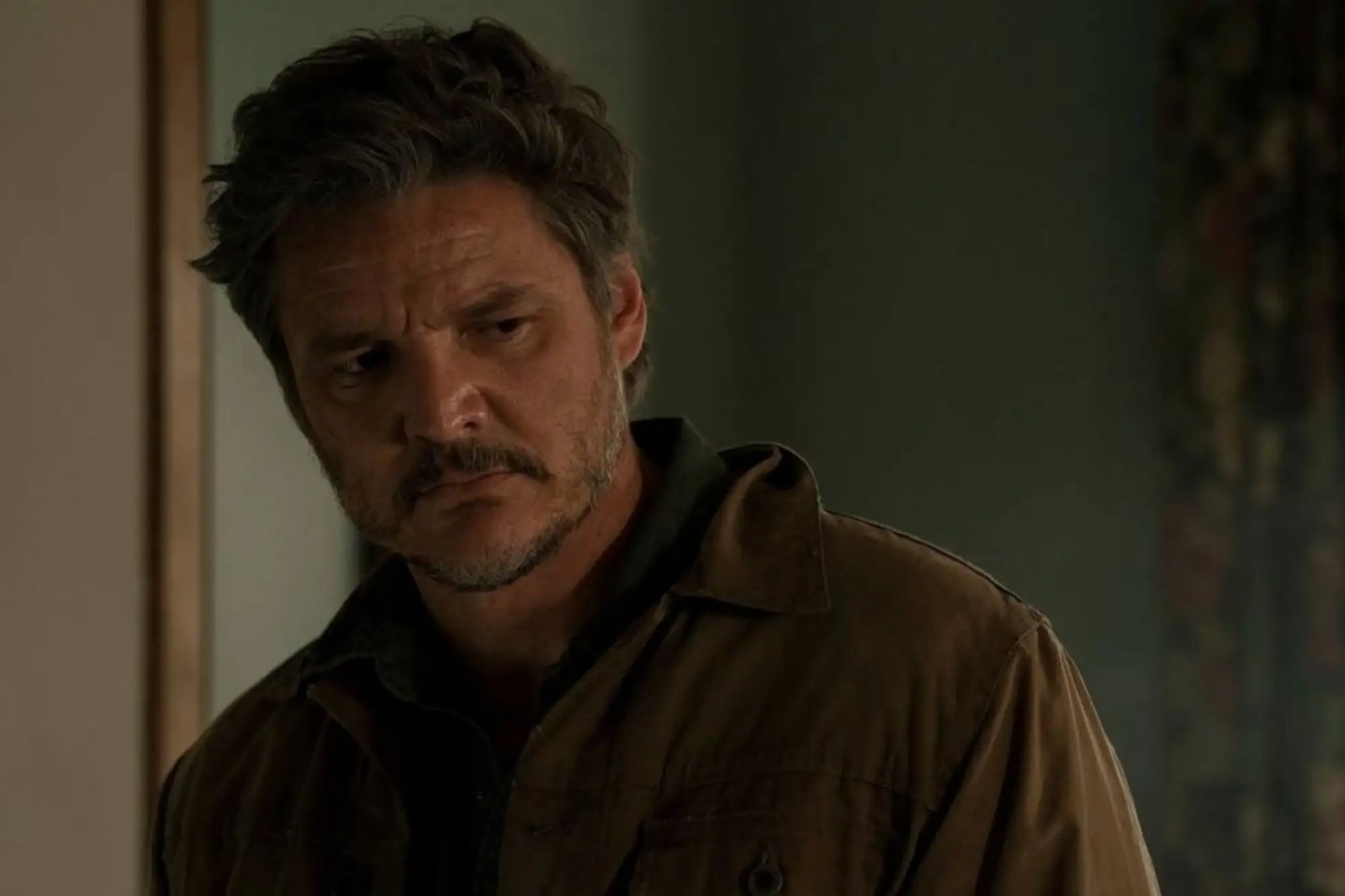

(featured image: HBO)

Published: Feb 3, 2023 07:15 am