When one adapts a video game into another medium, it reignites interest in the source material. Once The Last of Us premiered on HBO—not to mention became a huge hit—people were inspired not only to (re)visit the games, but also (re)visit older fandom discussions about it.

One topic that has reignited on social media is the connection between The Last of Us and The Last of Us Part II and the conflict between Israel and Palestine.

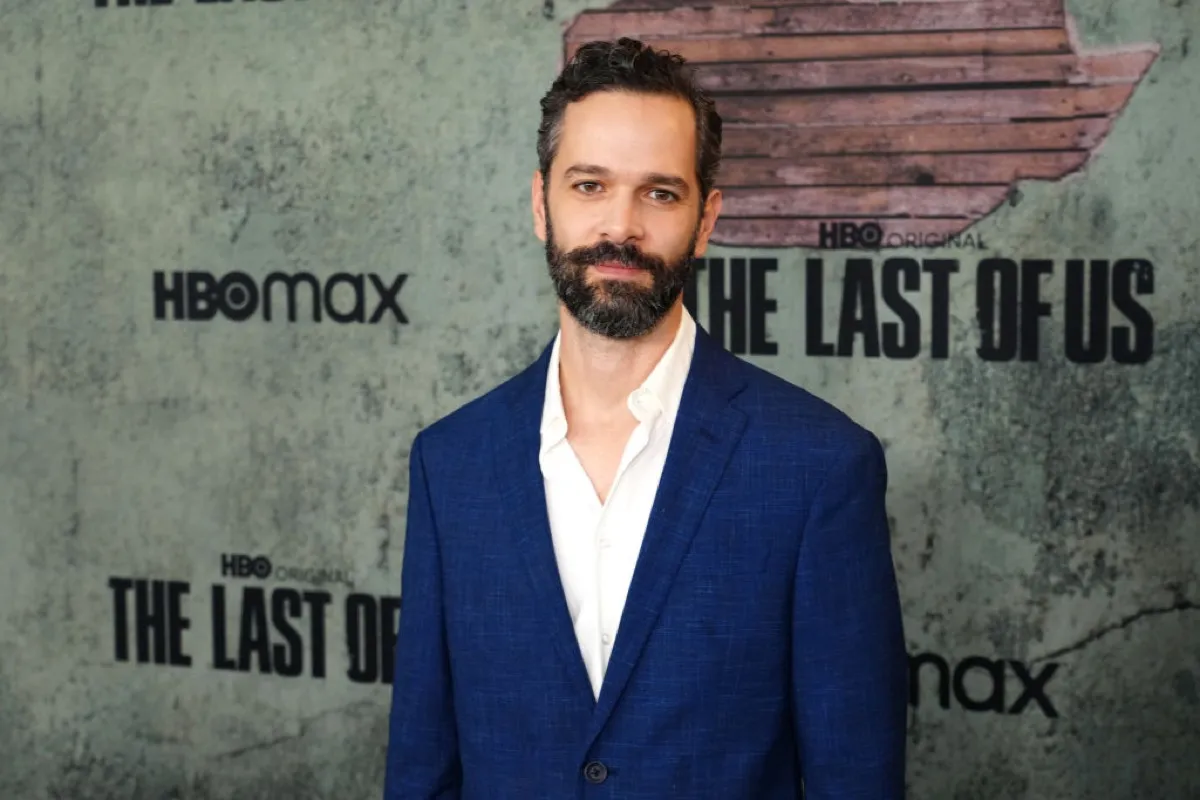

Reignited criticism of The Last of Us creator Neil Druckmann

Back in the summer of 2020, writer Emanuel Maiberg wrote a piece for VICE called “The Not So Hidden Israeli Politics of The Last of Us Part II.” It’s an interesting, if cynical take on the game (even as Maiberg views the game as a cynical take on human nature) by a Jewish writer concerned that Druckmann’s perspective on “cycles of violence” and how that’s portrayed in TLOU 2 is too centrist to provide a nuanced examination of that violence. Maiberg accuses the game of perpetuating “the very cycles of violence it’s supposedly so troubled by.”

This article has been making the rounds again, and fans have used it to criticize Druckmann in a less-than-nuanced way:

Neil Druckmann’s actual history, inspirations, and views

Some clarifications:

- Druckmann and his family left Israel in 1989, when he was 11. So, while he spent his first decade of life in Israel, he did most of his “growing up” in Miami, leaving Israel with a child’s understanding of his home country’s politics.

- Druckmann’s never said his game is “based on the Israel/Palestine conflict.” He has remained interested in Israeli politics even as an expatriate, and he’s cited incidents from his past that influenced specific plot points in the game.

On the official PlayStation podcast for The Last of Us, Druckmann cites the story of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit as the inspiration for Joel’s ultimate choice at the end of the first game/first season of the show.

In 2006, an armed squad of Palestinians who’d sneaked into Israel from the Gaza Strip took Shalit prisoner. After four years of negotiations with Hamas, Israel released 1,027 Hamas prisoners in exchange for this one soldier.

When 33-year-old Druckmann asked his father for his opinion, his father asked whether he wanted it as “the Prime Minister of Israel,” or “as a father,” because they’re very different answers. Druckmann’s father explained that, while this could be a bad move from an Israeli national security perspective, there’s nothing a parent wouldn’t do to retrieve an abducted child.

Druckmann went on to say,

“That’s what [The Last of Us] is about, do the ends justify the means, and it’s so much about perspective. If it was to save a strange kid maybe Joel would have made a very different decision, but when it was his tribe, his daughter, there was no question about what he was going to do.”

(The Last of Us Podcast)

The other memory Druckmann has publicly mentioned as an inspiration for TLOU is from 2000.

Over 100 Palestinian protesters (including minors) were killed in clashes with Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) over a two week period. Meanwhile, two drivers in the IDF reserve who were ordered to report to the Israeli settlement of Beit El ended up in the Palestinian city of Ramallah by accident. As Wikipedia puts it, “they had little army experience, were unfamiliar with the West Bank road system and drove through the military checkpoint […] and headed straight into the Palestinian town of Ramallah.”

Palestinian Authority police arrested and detained them on the same day as the funeral for a Palestinian teenager killed by Israeli settlers two days earlier. Tensions were high. Once word got out that there were two IDF soldiers at the local police station, Palestinians stormed it, injuring 13 Palestinian police officers trying to stop the riot, and killing the two IDF reservists. One was thrown out the window and was beaten and mutilated by rioters outside.

An Italian news crew captured footage of the killing, and 22-year-old Druckmann saw it. In a July 2020 interview with The Washington Post, Druckmann recalled that his initial reaction to seeing Palestinians cheering and proudly waving blood-stained hands was one of violence:

“It was the cheering that was really chilling to me. … In my mind, I thought, ‘Oh, man, if I could just push a button and kill all these people that committed this horrible act, I would make them feel the same pain that they inflicted on these people.’”

(The Washington Post)

Later, he felt “gross and guilty” about having felt that way. It’s this journey between his first, immature thought and his second, more mature thought that was the inspiration for Ellie’s evolution in the second game:

“I landed on this emotional idea of, can we, over the course of the game, make you feel this intense hate that is universal in the same way that unconditional love is universal? This hate that people feel has the same kind of universality. You hate someone so much that you want them to suffer in the way they’ve made someone you love suffer.”

(The Washington Post)

These memories inspired Ellie and Joel’s character development and choices. Druckmann doesn’t talk about them inspiring the politics of his game world.

It’s also important to note he had that violent, initial response to the Ramallah lynching when he was in his early twenties. He was inspired by his father’s response to the Shalit prisoner exchange and started working on TLOU in his early thirties, and he began work on TLOU 2 at 40.

The Internet tends to pile their “receipts” for a person’s views at once, as if they all tumbled out of a person at the same time. But Druckmann’s road through the memories he cites, to the games they inspired, to the HBO show accounts for over twenty years of personal evolution. A person’s views can develop all sorts of nuance in twenty years.

Interpreting The Last Of Us

YouTuber The Kavernacle provides a more nuanced analysis of Druckmann’s history and inspirations. He presents a clip from an interview Druckmann did with IGN Israel where the interviewer asked him if the extreme violence in TLOU 2 was meant to reflect the unforgiving world of the game. Druckmann replied,

“I think it’s a way to reflect the unforgiving world that we live in. You know, you live in a part of the world that constantly dealing with cycle of violence and retribution. I know it’s much more complex than that, but it’s hard to break that cycle. It’s really hard. Part of the themes, or part of the takeaway is that one side can’t stop. If only one side stops, it keeps going. So both sides have to let go. […] But the themes and the central questions are similar, like, ‘When should you stop? When is it too much to pursue justice at any cost?’ And the game ultimately deals with the limit that even if you are just, even if you are righteous, it can still destroy you to pursue it to the Nth degree.”

(IGN Israel)

The Kavernacle, like Maiberg of VICE, proceeds to use Druckmann’s inspirations to liken the Washington Liberation Front (the WLF; the “Wolves”) to the IDF and the Seraphites (the ‘Scars’) to Palestinians, going so far as to liken the look of the Seattle checkpoint to checkpoints in Israel’s West Bank—or, to liken the WLF’s leader, Isaac, and his ultimate plan to commit genocide against the Seraphites to Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians.

When I played TLOU 2, I was fascinated by the Seraphites. They reminded me of damn near every other American cult I could think of. Heaven’s Gate. The Branch Davidians. NXIVM. The Rajneeshees. I think of other game cults, too, like the Dolorians who follow Dolores Dei in Disco Elysium.

Each group elevates a charismatic leader who seems to have a connection to the divine that the rest of the group doesn’t. Each group’s followers gradually engage in increasingly disturbing behavior, and what may have initially been a good, well-intentioned idea turns ugly fast.

“What are the spiritual folks doing?” is an area post-apocalyptic stories usually explore. There are myriad responses human beings can have to trauma, and there will always be a place for a spiritually-focused group. So, I see the comparison of the Seraphites to Palestinians as a bit of a stretch. There’d be a need for a group like this in a story like this no matter the background of the game’s creator.

I’m glad The Kavernacle brings up FEDRA and that their closest real-life counterpart under the lens of this conflict is the British Mandate for Palestine. While he focuses on the Zionist response to the British, what I keep coming back to is the issue of a larger, outside power (Britain, the U.S.) deciding things for a region in which they have no personal stake, causing an already-existing rift to deepen, then leaving its inhabitants to fend for themselves after the creation of the State of Israel, stepping in only when it serves their interests and wondering why all this violence keeps happening.

In the same way that Britain and the U.S created a mess they couldn’t (or refused to) clean up, FEDRA caused the fracturing of the U.S. population into violent factions through its incompetence, its short-term thinking, and its increasingly violent and oppressive methods. FEDRA then collapsed, pulled out, or were forcibly replaced by native factions. This caused a cycle of violence that FEDRA didn’t have the sense or wisdom to anticipate. Or perhaps FEDRA just didn’t care.

People want to assign blame to the Israelis or the Palestinians, but rarely talk about how the rest of the world was complicit in pitting them against each other for capitalist gain in the first place. Every faction in TLOU started out as anti-FEDRA. Maybe that’s the point. Rather than fighting each other, they should remember the bigger enemy.

That said, using TLOU as a metaphor for the Israeli/Palestinian conflict is an interesting exercise, but has less to do with Druckmann’s intentions with the story and more to do with how people want to interpret TLOU.

Criticizing TLOU on its own terms

For many, that Druckmann spent his childhood in the West Bank—a fact over which he had zero control—is enough to draw conclusions about what he’s “trying to say” re: settler-colonialism. But having things from your personal life influence plot is very different than creating a story as propaganda for a particular cause.

Artists’ perspectives seep into their work, sometimes consciously, sometimes not. It can’t be helped. That’s what being an artist is: commenting on the world from one’s unique perspective.

Critics like Maiberg see Druckmann’s “cycle of violence” perspective as simplistic. In his VICE piece, he says “‘cycles of violence’ are a poor way to understand a conflict in a meaningful way, especially if one is interested in finding a solution.” He then likens the Israel/Palestine conflict to the U.S. invading Afghanistan for some reason before getting to, “Just as the fantasy of escaping violence by simply walking away from it is one that only those with the means to do so can entertain, the myth of the ‘cycle of violence’ is one that benefits the side that can survive the status quo.”

Maiberg isn’t wrong, but he’s criticizing the game for not doing something that it never set out to do in the first place. He mentions that we don’t see how the final showdown between the WLF and the Seraphites plays out, and this brings home the point that the WLF/Seraphite showdown was never the point. It was a backdrop. What matters is the conflict between Ellie and Abby.

Not every work is autobiographical, nor is every work trying to solve a problem. Some works are trying to examine a problem. In doing so, they provide their audience with a “way in” so they’re inspired to do the work of solving it in the real world.

So, I disagree with Maiberg’s assertion that Druckmann’s “cycle of violence” thinking “signals careful nuance while quietly squashing more difficult conversations.” If pieces like his, or mine, or The Kavernackle’s are anything to go by, nothing’s been “squashed.” It’s been the catalyst for more difficult conversations.

Druckmann set out to create games that focus on the personal. How do these characters feel and cope? How are these larger world issues resolved in the microcosm of these interpersonal relationships? If anything, Abby and Ellie are Israel and Palestine.

If we’re going to be using these games as a lens through which we can look at this conflict, we should do it using what the creator is actually giving us in-game and looking at what he’s actually saying in context, or we should leave him out of it, death of the author-style, and have our own, deeper conversation.

(featured image: Naughty Dog/Sony)

Published: Mar 30, 2023 04:27 pm