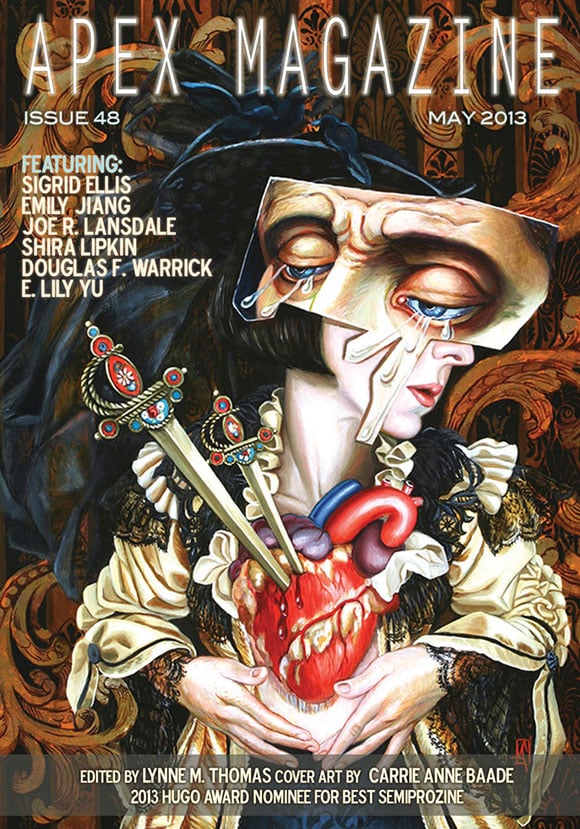

Editor’s Note: The Mary Sue is pleased to present a new ongoing monthly feature on the site. We’ve created a partnership to bring you unique new fiction from Apex Magazine‘s established and upcoming writers. We think they’ll be right up your alley. This month’s story, from Apex Magazine’s current issue, is “Ilse, Who Saw Clearly” by E. Lily Yu. Take a look…

“Ilse, Who Saw Clearly”

by E. Lily Yu

Once, among the indigo mountains of Germany, there was a kingdom of blue-eyed men and women whose blood was tinged blue with cold. The citizens were skilled in clockwork, escapements, and piano manufacture, and the clocks and pianos of that country were famous throughout the world. Their children pulled on rabbit-fur gloves before they sat down to practice their etudes, for it was so cold the notes rang and clanged in the air. It was coldest of all in the town on the highest mountain, where there lived a girl called Ilse, who was neither beautiful nor ugly, neither good nor wicked. Yet she was not quite undistinguished, because she was in love.

One afternoon, when the air was glittering with the sounds of innumerable pianos, a stranger as stout as a barrel and swathed to his nosetip walked through the town, singing. Where he walked the pianos fell silent, and wheat-haired boys and girls cracked shutters into the bitter cold to peep at him. And what he sang was this:

Ice for sale, eyes for sale,

If your complexion be dark or pale

If your old eyes be sharp or frail,

Come buy, come buy, bright ice for sale!

Only his listeners could not tell whether he was selling ice or eyes, because he spoke in an odd accent and through a thick scarf.

He sang until he reached the square with its frozen marble fountain. The town had installed a clock face and a set of chimes in the ice, and now they were striking noon.

“Ice?” he said pleasantly to the crowd that had gathered. He unwound a few feet of his woolen cloak and took out a box. The hasp gave his mittens trouble, but finally it clicked open, and he raised the lid and held out the box for all to see. They craned their necks forward, and their startled breaths smoked the air.

The box was crammed with eyes.

There were blue eyes and green eyes and brown eyes, eyes red as lilies, golden as pollen; eyes like pickaxes and eyes like diamonds. Each eye had been carved and painted with enormous care, and the spaces between them were jammed with silk.

The stranger smiled at their astonishment. He unrolled a little more of his cloak and took out another box, and another, and then it was clear that he was really quite slender. He tugged his muffler past his mouth, revealing sunned skin and neat thin lips.

“The finest eyes,” he said to the crowd. “Plucked from the lands along the Indian Ocean, where the peacock wears hundreds in his tail. Picked from the wine countries, where they grow as crisp as grapes. Young and good for years of seeing! Old but ground to perfect clarity, according to calculations by the wisest mathematicians in Alexandria!” His teeth flashed gold and silver as he talked.

He ran his fingers through the eyes, holding this one to the light, or that. “Is this not pretty?” he said. “Is this not splendid? Try, my good grandmother, try.”

That old woman peered through eyes white with snow-glare at the gems in his hands. “I can’t see them clearly,” she admitted.

“Well, then!”

“Lucia,” she said, touching her daughter’s hand. “Find me a pair like I used to have.”

“How much?” Lucia said.

“For you, the first, a pittance. An afterthought. Her old eyes and a gold ring.”

“Done,” the old woman said. Lucia, frowning, fingered two eyes as blue as shadows on snow.

The stranger extracted three slim silver knives with ivory handles from the lining of his cloak. With infinite care and exactitude, barely breathing, he slid the first knife beneath the old woman’s eyelid, ran the second around the ball, and with the third cut the crimson embroidery that tied it in place. Twice he did this. Then, in one motion, he slid her old eyes out of their hollows and slipped in the new. Her old blind eyes froze at once in his hands, ringing when he flicked them with a fingernail. He dropped them into his pockets and tilted her chin toward him.

“I can count your teeth,” the old woman said with wonder. “Your nose is thin. Your scarf is striped red and yellow.”

“A wonder,” someone said.

“A marvel of marvels.”

“A magician.”

“A miracle.”

She pulled off her mitten and gave him the ring from her left hand. “He’s been dead twenty years,” she said to Lucia, who did not look happy. “I can see again. Clear as water. What a wonder.”

Then, of course, the stranger had to replace the shortsighted schoolteacher’s eyes, after which the old fellow cheerfully snapped his spectacles in two; the neglectful eyes of the town council; six clockmakers’ strained eyes; crossed eyes; eyes bleared with snow light and sunlight; eyes that saw too clearly, or too deeply, or too much; eyes that wandered; eyes that were the wrong color.

When the sun was low and scarlet in the sky, the stranger announced that he would work no longer that day, for want of illumination. Half the town immediately offered him a bed and a roaring fire. But he passed that night and many more at the inn, where the fire was lower, colder, and less hospitable, and where, it was said unkindly, one’s sleeping breath would freeze and fall like snow on the quilts. He ate cold soup and sliced meats in the farthest corner, answered all questions with a smile, and went to bed early.

After twelve days he bundled his boxes about him and left the town, his pockets sunken and swinging with gold. The townspeople watched as he goat-stepped down the steep trail until even their sharp new eyes could no longer distinguish him from the ice-bearded stones and the pines and the snow.

These new eyes, they found, were better than the old. The makers of escapements and wind-up toys found that they could do far more delicate work than before, and out of their workshops came pocket watches and pianos carved out of almond shells, marching soldiers made from bluebottles, wooden birds that flew and sang, mechanical chessboards that also played tippen, and other such wonders; and the fame of that town went out throughout the whole world.

Summer heard, in her house on the other side of the world, and came to see.

The first notice they had of her approach was a message in a blackbird’s beak, then a couple red buds on the edges of twigs, and then she was there. Out of respect she had put on a few extra flowers this year. It was still cold–summer high in the mountains is like that–but the air was softer, the light gentler.

No one saw her courteous posies, however. A little before she arrived, their eyes had begun to blur, then blear, then melt. They saw each other crying and felt their own tears running down their faces, and for no reason at all except summer. Then they understood, and wept in earnest, but it was too late.

By summer’s end everyone had cried out the new eyes. The workshops fell still and silent, and tools gathered tarnish on their benches. The hundreds of clocks around the town stopped, since no one could find their keys and keyholes to wind them up again. Only the pianos still rang out their frozen notes now and again, but the melodies were all in minor keys. The town was full of a cold, quiet grief.

Winter was coming, and they would have starved without Ilse, who hadn’t sold her eyes. Her sweetheart had written atrocious poems to them, and although they were the same plain blue as anyone else’s, she couldn’t bear to part with them even for new eyes the colors of violets, blackberries, and marigolds. So she helped the town tend and bring in its meager harvests of beets and cabbage, and on Wednesdays she filled a sack with clocks and toys and went down the mountain to sell them at market, until there were none left. During the day her head swam with the pianos’ lugubrious complaints, and at night she ached in every bone.

“Mother,” she said, as they ate their bare breakfast together, “shouldn’t someone go looking for the surgeon?”

“No one will find him.”

“What will you do if you never find your eyes?”

“We’ll manage. We have you to see for us.”

“I’m going to look for him,” she said.

“Absolutely not.”

So Ilse packed up her summer clothes, a loaf of bread, two onions, and the fourteen silver coins her mother kept in a jar on the shelf, and the next day she set off down the mountain.

In all her sixteen years, she had never strayed beyond the market in the shadow of the mountain, where the town’s clocks and pianos were sold. But now she passed town after town, few of which she knew, and bridges, and streams, and meadows stained with the dregs of summer, and now trees that did not stand as straight as soldiers but spread their shoulders broad and wide. She climbed up one of these as night fell, and tucked her head against her knees, and slept.

A soft noise, like paper or feathers, woke her in the middle of the night. Ilse opened her eyes in fear, expecting robbers and thieves, but saw nothing. Still she was full of dread. She thought of the silver she had stolen, and her sightless mother in a silent house, and her sweetheart, lonely and wondering. She thought of the long road ahead of her, with likely failure at its end, and shivered. For where could she begin to look?

“You are thinking too loud,” someone said close to her ear. She nearly fell out of the tree. Next to her, an old crow shifted from foot to foot, cleared its throat, and spat.

“You can talk?”

“Only when people’s thoughts are so noisy I can’t sleep.” It sighed. “What would it take to quiet down your brain?”

“I am looking for my townsmen’s eyes.”

“Eyes!” The crow whistled. “A treat, a delectable treat. I should follow you.”

Ilse snatched sideways, swiping a bit of dark down between her fingers. The crow tumbled out of the tree with a screech.

“You’ll do no such thing,” she said.

“Peace, peace.” A wing brushed her brow. “You’ll find what you’re looking for. You’ll find your sight, and theirs. And you’ll not like what you see when you see the world truly, too-quick girl with the odor of onions.”

He flapped his way to a higher branch; she could hear him combing out his rumpled feathers. “I don’t take kindly to being grabbed at, onion girl.”

“Just let me find what I’m looking for,” she said, and shut her eyes. Afterwards, but for the bit of down stuck to her clothes, she could not say whether she had dreamt it all.

* * *

On the third day, as she trudged down the road that went nowhere she knew, she met a flock of spotted goats with yellow bells about their necks, and then their shepherd, who was chewing a stalk of grass. He greeted her, and she asked with no great hope whether he’d heard of a peddler of eyes.

“Yes, miss,” he said. “Walk a little farther, until you reach a village with sunflowers around it, and go down the street to the last house. My daughter is home, and she knows much more about your magician than I do.”

Ilse thanked him and went on. The village ringed by sunflowers was smaller and muddier than her own, and the road ended at the smallest and muddiest house. The cat on the roof had only half his coat, as he had been a fierce warrior in his day, but he opened one eye and yawned at her. A young woman opened the door. Asked about the peddler, she smiled and winked her eyes one after the other. One of them was a shade greener than the other.

“I lost this one falling out of a window. My father and I waited four years before the good man came back. We had nothing to pay him with, at least nothing worth it, and I would have gladly taken a grandmother’s cataract. But he said I was a lovely girl and picked out a greener eye than my first for me. A sweet soul.”

“He left my village blind.”

“You must be mistaken. He wouldn’t do such a thing.”

“He has three silver knives with ivory hafts, with ivy engraved in the ivory. His skin is dark and his nose is sharp.”

“Well,” the goatherd’s daughter said. “Well. He does look like that. And he does have three knives. But I really don’t think—”

“How can I find him?”

“Now, that’s tricky. That will take a little explanation. But you’re in no rush, are you? He doesn’t travel quickly, and you don’t look like you’ve eaten yet today.” She hewed a generous piece of brown bread for Ilse and poured out a bowl of cream for her, as well as a bowl of milk for the cat.

“I still think you’re wrong somewhere. Surely he wouldn’t. So kind.”

Ilse ate the bread and drank the cream so fast she left a crumb on her cheek and a pale spatter on her chin.

“Now,” the goatherd’s daughter said presently, “you’ll be going to the city. If you unraveled today down the road, you’d find the city at the end of next week. There are three towers at the corners of the city, with three broad streets between them, and where the streets meet is a brick square. Ask in the square where your magician might be. Someone there will know more.

“But you’re not taking the road in those clothes, are you?”

Ilse was suddenly aware of how heavy and hot her woolen summer smock and rabbit-fur cloak were, and how strongly they reeked of onions.

“Let me find you something lighter. You can leave those here, for when you return.”

So Ilse exchanged her fur and wool for an armful of patched but comfortable linen, put a piece of bread and a slice of cheese in her pocket, and continued on her way. Now and then she passed a farm cart creaking on its way. Now and then, with a nod from the driver, she climbed into one of those cart and rested. She came upon a few crows pecking in the dust, but though she greeted them politely, they never answered.

The longer she traveled, the closer together grew the villages and fields. She was tired of the road and the yellow dust that lay in a film on her mouth, and she thought many times of her soft bed at home, and the color of her sweetheart’s hair, and the air as pure as snow. Sometimes she considered turning around, but she never did. After wearing out her shoes by the thickness of seven days, she saw, black against the evening, three towers as formidable as teeth, and that was the city.

A soldier in fine scarlet-and-cream stood to attention at the gate, which was barred. He had a silver spear in his hand and silver mail beneath his tabard.

“It’s past sunset,” he said, frowning at her through his helmet. “No one enters or exits the city at night. Go home.”

She said, “My home is in the mountains, but I’ve come looking for a magician, a doctor, who can take the eyes out of your head and put them in again. He took all the eyes out of our town.”

“I’ve heard of such a doctor,” said the soldier. “He mended my fourth cousin’s weak eyes, years ago. But you can’t mean him. He wouldn’t do such a thing.”

“Perhaps it was unintended.”

“You’d do well to ask in the square tomorrow. Tomorrow, mind you. I cannot let you through.” He held his spear a little straighter. “Unless you can show me something as bright as sunlight. That might fool me for a little while.”

“I only have a little silver,” she said, patting her pockets. But they were empty.

“Moonlight will do.”

“No, I have nothing. I left my silver in my smock, and I left my smock at a goatherd’s cottage, and that’s a week’s walking.”

The soldier huffed into his moustache. “What a foolish girl you are.” He took a key from his belt and opened a low door in the gate, just tall enough for her to slip through. “I have a little one your age, just as silly as you. You’d feed yourself to wolves if I kept you outside. Hurry up, won’t you. And stay out of trouble.”

“Thank you,” Ilse said, and he shut and locked the door behind her.

Here and there the flame in a lamppost flickered and swayed. There were many more streets than she had expected, running every which way. Uncertain of what to do, she went back and forth, past dark windows and bolted doors; open doors with laughter, hectic music, and light spilling out of them; past rubbish in the gutters and pools of water shining in the dark. Shadows slid past her, silent and purposeful. She felt unseen eyes following her.

At last, lost and dispirited, she peered into a shop window and saw a vitrine lined with pocket watches and the pale faces of tall clock cases in the dimness beyond. Some of them looked familiar. She pressed her nose to the gold-lettered glass, wondering if she knew the hands that had made them. She wanted very much to touch them, but the door was locked.

There was nowhere else she could go. She sat down in the doorway and put her head in her hands and, unwillingly, fell asleep.

If strange hands rifled her pockets while she slept, they found nothing, and she did not know. When she woke, it was morning. An old man with a broom was standing over her, displeased.

“Well, get along now,” he said. “Go on.” He held the shop door open and swept a little dirt over her, then tried to sweep her off the step.

“Please, which way to the square?”

“Which way to the square?” The shopkeeper stared. “Are you mad?”

“I came into the city yesterday,” she said.

“With no place to stay? You are mad.”

“Won’t you tell me?”

“Never let it be said I was uncharitable toward the insane,” the shopkeeper said. He disappeared into the shop–a bell jangled inside–and just as she decided to leave, reappeared with a small stale cake.

“There you go,” he said. “Down the lane, a left, a right, a right, a left, a right, two more lefts, and you’re there.” And he went back into the shop.

The square was broader than she expected, and busier, lively with stalls and carts and striped awnings, the glitter of gold and silver on tables, the odors of fruit and fish and spices, the squabble of bargainers and women shouting apples.

Weaving her way through the tables and crowds, dazzled and bewildered, she stopped beside a table set with magnificent glass apparatuses: telescopes, periscopes, beakers, loupes, spiral condensers, burning glasses, spectacles. Behind a towering stack of old books sat the glassblower, his nose in a book, a mole at the tip of his nose. She asked whether he knew the magician.

“Of course! Of course!” he snorted.

“Where can I find him?”

“Why, he’s marrying our Queen next month! Only,” he said, and winked, “no one knows that it’s him, our peripatetic physician, our humble expeller-of-drusen, ablator-of-sties. Word is she’s betrothed to a Solomonic magician from far away, the Indies, the Sahara, what have you. But she’s had milk eyes from the day she was born, our poor Majesty, and only one fellow could have fixed those. The usual reward, of course, would have been half the kingdom, or ennoblement and emolument. But he’s a handsome one, our doctor. And ambitious. Why are you looking for him? Did he steal your heart, too?”

She told him.

“Ha! What a mistake to make. It’ll be easy to find him. He’s caged in the royal palace; you can’t miss it. Finest house in the city, and no one can have finer, for fear of beheading. Tallest house in the city, too, by law. She had all the weathervanes sawn off the churches, and would have chopped down the towers, too, except they persuaded her to build her house a little taller. You can see it from here.”

It was indeed the finest house in the city, ringed by green gardens and ponds full of tame swans. Guards bright with old-fashioned weapons marched around its perimeter.

She crumbled a bit of her cake for the swans as she pondered what to do. Then she looked at the wet black legs of the swans.

It was not easy to tear one of her skirts to strips; she had to put her teeth to it. Every four inches she tied a loop, and when she had finished she spread it loosely and broke the rest of the cake over it. As the swans stabbed up the crumbs, she eased the knots shut around their scaly legs. Then she tugged. One of the swans hissed and bit her finger, but the rest, startled, took off in a white cloud. Clinging to their feet for dear life, she rose higher and higher in the air.

Once she was dizzyingly high above the city, she untied the swans one by one, until she held a single blustering cob by the feet. They sank together through the air, landing painfully on the tiles of the palace roof; and then she let him go, as well, and looked about her.

In one corner was a hunchbacked tower, patchy with lichen. To her left and right the castle walls plunged below the eaves. Ilse scrabbled across the slate tiles, kicking one loose–it skittered down the sloping roof and vanished over the edge–and losing a shoe. When she came to the open window she hauled herself up and into a rich bedroom.

A goat-slender man, studying himself in his mirror, whirled around at the noise. She thought she recognized the pointed nose and chin, the glittering eyes.

“Who are you?”

The room was hung with tapestries; the bed was spread with silks and velvets; even the magician’s coat glittered thickly with jewels. She was suddenly, painfully aware of the patches on her clothes. But she thought of her sweetheart and mother, and she stood up straight and addressed him.

“Now!” the magician said, after she had finished her story. “I never meant to do that! I cut ice eyes for you because I thought they’d never melt.”

“Will you give them their eyes back?”

“Impossible. Others needed them.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I am going to marry the Queen in a month,” he said. “It’s about time I settled down. She’s a lovely woman. Proud, though. She won’t permit me to work as a petty physician. Must marry a man of leisure, you know. I can’t even make you new eyes of rock crystal and glass. Who would restore them?”

“So you are leaving my town blind,” Ilse said. “So you have taken away their eyes, their wedding rings, and their livelihoods, and you’ll never return them. You are going to marry a Queen and live, as they say, happily ever after. What a marvelous magician you are!”

He hesitated. “That’s putting it rather badly. I could teach you, I suppose. If you are intelligent enough. If you are nimble enough. It might take five years, or ten, depending on how quickly you learn.” He glanced doubtfully at her clothes. “But afterward you could restore sight wherever you wished.”

“Yes,” Ilse said.

“But we must first ask the Queen.”

They found the Queen reading Schiller with her feet propped on a leather ottoman, now and then weeping a decorous tear. She was not a cruel woman. She listened to Ilse’s story and sighed, and afterwards gently reproached her betrothed. But their request displeased her.

“Am I to give you up, my love, for ten years so you can train the girl?”

“Hardly–”

“You may have his instruction,” she said to Ilse, “for one year. I will postpone the wedding for that long, because it is unseemly for a King to teach surgery. But after one year we shall marry, and you will go home.”

Grateful and dismayed, she kissed the Queen’s white hand.

And so for a year she studied under the magician, by sunlight, moonlight, and candlelight, paging through abstruse medical texts and reproducing in wet, squiggling lines on blurry paper the elegant anatomical diagrams her teacher marked with a finger. Often she went without sleep and food in her haste to learn.

The magician taught her the structure and composition of the eye, its fine veining, innervation, and musculature; the operation of light and color; sixteen theories of sight from philosopher-doctors in various kingdoms; and common diseases and their remedies. All of this, he said, he had gathered from years of wandering in strange lands among strange people. And when she was exhausted with studying, he told her stories from his travels.

In the flicker of shadows on the wall, her eyes unfocused from much reading, she thought she could see the people he described: the woman who married a tiger, the parrots who kept state secrets, the ship that flew in the air. She fell asleep in her chair with his words still running in her ears, and he dropped a coat over her before he retired, and so they passed many nights.

By the end of the year she could switch the eyes of rabbits, cats, and sparrows without harming them, without even a drop of blood falling on the magician’s knives.

“All that I can teach, you know,” he told her one night. “Take my knives, and take this box. I have had time to fashion new eyes for you and yours. Glass and rock crystal, this time.”

She fell on her knees and thanked him.

“But there is one more thing. I know no one as quick and capable as you, or as kind. If you will have me, I will marry you instead of the Queen.”

“That is kind of you, but I have a sweetheart at home,” Ilse said.

“He won’t have waited for you.”

“He has. I am certain.”

“Very well,” he said, annoyed. “Go home to him, then.” He was not gracious enough to invite her to the wedding, or even to replace her tattered clothes. So with the box under her arm, and the three silver knives hung at her side, Ilse left the palace.

The soldier at the gate barred her path with his spear. He had a hard face and a rough red beard.

“What are you carrying, girl?”

“Eyes that the Queen’s magician gave me.”

“Gave you? You in those rags? Unlikely. An export fee of three gold crowns.” He laughed at her. “Of course you can’t pay. But you’ve a pretty face, and I’ll overlook this for a kiss.”

She turned to go.

“Or,” he said thoughtfully, “I could have you arrested and imprisoned. For theft, probably.”

And she saw that he meant it. So she kissed him on his bristly mouth, a sick twist in her stomach, feeling his hands slide up and down her sides, and then he laughed and waved her through.

The road seemed twice as long now. The days grew colder as she went, for it was autumn again, and her clothes were thin, and the road was rising toward the mountains. The crows in the trees croaked and chuckled as she passed.

After many days of weary walking, she saw with great relief the goatherd’s village. The sunflowers were brown and rattled in the wind, but the cat still sat on the goatherd’s roof, and it stretched and purred at her.

She rapped on the door. The goatherd’s daughter opened it slightly. Faint lines were sketched into her forehead. Somewhere in the cottage, a child began to wail.

“What do you want?”

“I left a wool smock and a fur cloak with you. Last year, it was. And there were fourteen pieces of silver in the pocket.”

“I don’t know what you are talking about.”

“You fed me and you gave me these clothes to wear. Don’t you recognize them? Keep the clothes, if you like, but please give me my mother’s silver.”

“We feed paupers all the time. Of course I can’t remember each one. But there’s no food in the house today. There’s no food in all the village.” She shut the door.

Ilse had no choice but to continue. The higher she climbed, the colder it was, and she shivered when she lay down to sleep on the lichen-studded stones. But she kept herself warm remembering her sweetheart’s smile and her mother waiting for her in darkness.

At last she heard the faint sound of pianos. Tired though she was, she quickened her pace. Soon she saw woodsmoke in the sky, then chimney pots, then houses.

It was as she remembered it. Only now the notes that rang in the cold air were cheerful, and the people walked as though they could see. Ilse went into her own house and found her mother slicing vegetables.

“Ilse?” the woman said uncertainly, lifting her face. Ilse caught it in both hands and kissed it.

“Mother, you’ll never guess where I’ve been.”

“Out into the world. But what are you wearing? Go put on something warm.”

“Not yet. Hold still.” And with practiced gentleness, Ilse set two blue eyes in her mother’s face.

* * *

She visited her sweetheart’s, then. She ran to him and embraced him and he said, “Ilse?”

“Yes, it’s me, I’m home.”

“Oh, Ilse–I’m happy you’ve come back.” He paused. “This is Elsa–the goldsmith’s daughter–I married her in the spring.”

“How wonderful.” She kissed him on the cheek. “I have something for both of you.”

* * *

After a fortnight of careful work, all the town could see again. It turned out that they had fared well enough without their eyes. Ilse was well wished, well fed, blessed, and thanked, and made to tell her story again and again, until the smallest child could recite it. It was pleasant being home. She had missed the sound of ice-tuned pianos and the sweet mountain wind.

When Elsa the goldsmith’s daughter gave birth, all agreed that the blue-eyed girl would be a matchless beauty and a legend in the kingdom. Her father wrote achingly terrible sonnets to those eyes.

Sometimes Ilse stood at the edge of town and looked over the world that fell away from her, farther than she could see. Sometimes she wondered how the magician and his Queen fared. More often, though, she thought of the strange lands he had told her about, where he had learned his strange arts: jewel-colored jungles, thick with flowers and snakes; or white sands running into a green sea; or dark pine forests alive with deer and wolves and red foxes. She would sit at the mountain’s edge until her face was numb with cold, looking, wondering.

* * *

One day, no one could find her.

© 2013 E. Lily Yu

Please visit Apex Magazine (www.apex-magazine.com) to read more great science fiction, fantasy, and horror.

This story is from issue 48 (May, 2013). The issue also features fiction by Emily Jiang (“The Binding of of Ming-tian”), Douglas F. Warrick (“Come to My Arms, My Beamish Boy”), and Joe R. Lansdale (“Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man’s Back”), nonfiction by Sigrid Ellis (“Kicking Ass, Taking Names, Bubblegum Optional”), an interview with Joe R. Lansdale, and poetry by Shira Lipkin (“The Busker, Broke and Busted”).

Each issue is free on our website, but Apex sells nicely formated eBook editions for $2.99.

Published: May 7, 2013 12:30 pm