How Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf’s Refusal to Stand for the National Anthem Taught Me About Racial Injustice

Twenty years before Colin Kaepernick, the NBA's Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf refused to stand. The repercussions were swift.

By the time I was watching the Nuggets, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf was already Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf. There were definitely some people I knew, mostly adults, who with a bigotry I didn’t recognize yet would insist on saying that his real name was Chris Jackson. It didn’t mean anything to me, and I wasn’t inclined to understand even what a “real name” would even be, let alone the nasty history this was part of, the echoes of the old white men who insisted on calling Ali “Cassius,” and Abdul-Jabbar “Lew.”

Because all of this was new to me. Following sports was new to me, racism was new to me, Islam was new to me. My life to that point had been spent in the comfort of the Denver suburbs, enveloped from all directions by white privilege and taught in school the typically 90s version of racial history in the United States, with its emphasis on color-blindism. That, “if you notice someone’s black, you’re being racist,” and it’s always close-behind corollary, “if black people talk about race, they’re the racists.”

So, in my wide-eyed, childish analysis of the information I was receiving about Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf and his “real name,” what it came down to for me was that Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf was a hell of a lot more interesting sounding and fun to say than Chris Jackson, and I didn’t need much more of a reason than that to stick with it.

But this was before the National Anthem thing. I was driven into the arms of sports by the same two things that drive so many kids who are not themselves athletically inclined or interested into sports, which are the search for a way to connect with my dad, and a need to have something to say to the other kids at school. I was a voracious reader and memorizer of trivia with an old man’s love of wordplay and a sinking feeling I didn’t fit in. The type of kid who had a favorite dinosaur, but not a favorite quarterback. To my great and lasting happiness, it turns out that this is a combination that leads to being a particular type of sports fan, which is the stats nerd, or the history nerd, which is the type of sports fan I remain.

It was, in its way, counterproductive to my aim of having something to say at school that I started following the Denver Nuggets. It was aggressively unfashionable, even in the suburbs of Denver, to be a Nuggets fan. The reason was that they sucked, and I can see now that the kids at school dealing with their own adolescent insecurities might at least want to present themselves as Chicago Bulls fans or New York Knicks fans at school so they could be, in some sense, a winner. But I felt bound by geographic loyalty, and there was nothing I could do about that.

So while other kids, maybe really approaching sports fandom in a saner way where it’s about supporting the team that’s going to win instead of the one from your hometown, were at school extolling the virtues of Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen, I became an instant and deeply passionate fan of Dikembe Mutombo, LaPhonso Ellis, and Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf. (It’s almost worth not saying because of how on-the-nose it is, but I suspect if you’d taken a poll of my classmates around then, the three favorite players wouldn’t have been any of the above, but rather Larry Bird, John Stockton, and Chris Mullin.)

If the first thing I noticed about Abdul-Rauf was his cool name, the second was that he had Tourette’s and a little tic where his head would snap back quickly from time to time, which we would mimic when we played basketball in the schoolyard. The third was that he was the Nuggets’ leading scorer for four years running, and the fourth was that lots of the grownups I knew seemed to harbor some kind of resentment, or suspicion, of him. This was before the National Anthem thing.

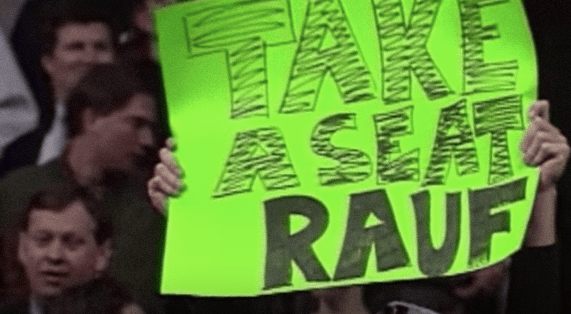

The Anthem thing came in the 1995-96 season, when I was 11. For the first three-quarters of the season, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf had not been standing with the team for the National Anthem. He wasn’t even as conspicuous about it as Colin Kaepernick would end up being 20 years later: he would stay in the locker room, or stretch. Nobody noticed, and nobody had a problem with it, until some sports radio guys started paying attention.

When Abdul-Rauf was asked about why he wasn’t participating in the pre-game patriotism ritual, he said that his Muslim faith wouldn’t allow him to worship any God but Allah—and that the stars-and-stripes, to him, stood for tyranny and oppression.

Almost nobody had his back. The NBA vowed to suspend him without pay for every game where he refused to stand. The league’s most prominent players tended to either actively distance themselves from him, or hedge their support. The NBA’s most prominent Muslim, Hakeem Olajuwon, told the New York Times that it was “tough for me to understand his position,” and Michael Jordan said, “I can understand him sitting in the locker room and coming out after the national anthem, but being out there on the court while everyone else is standing, that is being disrespectful.” (A retrospective shout-out is due to Steve Kerr, who as coach of the Golden State Warriors, has been so spot-on in his handling the Steph Curry/Donald Trump thing, and who was publicly backing Abdul-Rauf in ‘96.)

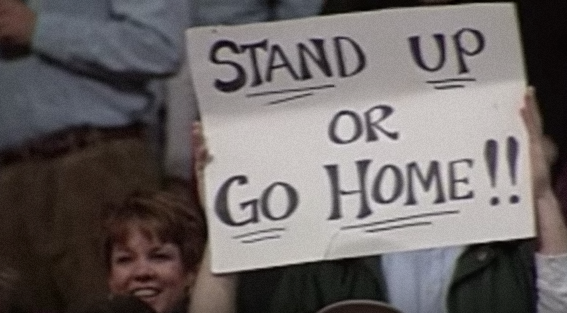

In Denver, among his supposed fans, the reaction was obnoxious, callous, and racist. Fans started booing him, sometimes in a weird echo of the boos we heard during the anthems at various NFL games recently, where Sunday patriots were so motivated by their love of flag, country, and song, that they loudly booed through the National Anthem as a way to demand respect for it.

A Denver Post poll showed that 72% of Nuggets fans were opposed to Abdul-Rauf’s protests and, in the most publically egregious example of the response, two idiot shock jocks from KBPI and one of their idiot listeners barged into the mosque down the street from where I lived and played the “Star-Spangled Banner” on a bugle. (They were fined.)

But for 11-year-old me, it wasn’t so simple. It can be hard to try and describe the importance of sports as pop culture and social metaphor to people who have never looked at this way before. Here I mean the people who think it’s cute to call it “sportsball,” or for whom the idea of sports only bring memories of high school jock bullies and high-fiving, Elway-jerseyed alpha males drinking shitty beer at the bar you like every day but Sunday.

But Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf caused me, for the first time in my sheltered and privileged life, to think about racial injustice. To think about Islam, and a genuine meaning of religious freedom. For me, who had never had occasion to question the meaning of our national symbols, much less the country they symbolized, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf was an awakening. And it was precisely because he was a basketball player I idolized, whose tics I imitated on the court, that I was open to hearing what he had to say. Everything he said about why he was doing what he was doing made an instinctive kind of sense to me. Even the whitewashed, sanitized version of Black History I had gotten in school to that point gave me enough to make the connection between what he was doing and what Rosa Parks or Martin Luther King had done.

It’s tempting to say, glibly, that I was not the target audience for Abdul-Rauf’s protest. One of the coolest things about his protest, though, is that it had no target audience. Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf’s decision to protest the national anthem was about his conscience, his convictions, and his faith. He didn’t care (and still doesn’t, as he made it clear in recent profiles in The Undefeated and The Nation) what 72% of Nuggets fans, the NBA, or Hakeem Olajuwon and Michael Jordan thought.

For me, even as an 11-year-old with no concept at all of the history he was following or the risks he was taking, the courage resonated. It’s obviously too easy to say that Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf alone opened my eyes to racial and religious injustice, when life is messier than that, and causes and effects less clear, and the journey to genuinely have open eyes ongoing. But it is true without question that Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf meant something to me, even if I couldn’t identify what. And it’s true that my road out of the arch-conservative, unblinkingly evangelical values of my suburb and my school, of so much as having the desire to know more than I do or recognize my white privilege blind spots, started with his refusal to stand.

This is what sports can mean. Or, more specifically, this is what athletes can mean. Besides the often beautiful and often disturbing way sports reflect and re-create the society in which they’re played, there is the athlete as hero, the athlete as pop culture star, the athlete as activist.

What I know now that I didn’t know when I was 11 is that what happened to Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, his blackballing from the NBA, the easy racism people reached for in their responses, was a microcosm of the expectation we put on successful black people to shut up and be grateful. And his insistent dignity in the face of it, the way he still to this day has no regrets, is an inspiration and a model going forward.

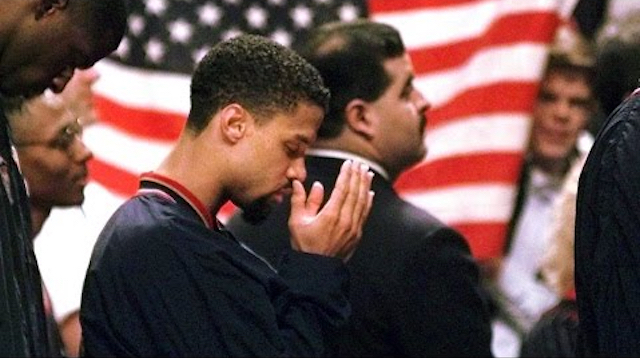

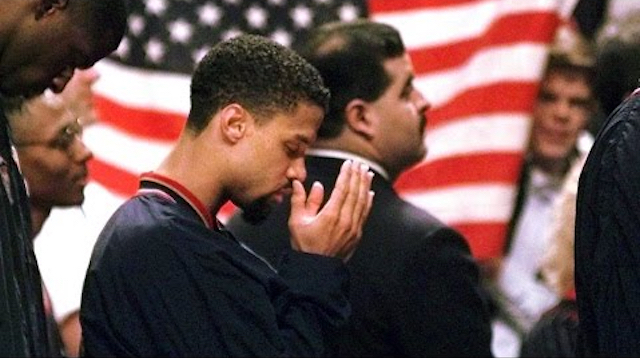

Eventually, Abdul-Rauf found a compromise with the NBA, where he would stand for the National Anthem, but lift his hands, close his eyes, and silently pray during its playing. The NBA’s good faith in the compromise was shallow and short-lived. Within a couple of years, he was run out of the NBA, instead moving to a Turkish team, beginning a long sojourn that took him to Russia, Italy, Greece, Saudi Arabia, and Japan.

And in 2016, when Colin Kaepernick was hearing the same bullshit Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf heard 20 years earlier about how he should be grateful for a country that’s made him a millionaire, and shut up and play, and that he’s not on a team because he’s not good enough, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf was playing in the Big3, Ice Cube’s 3-on-3 league for retired NBA stars. And he was standing for the national anthem, eyes closed, palms up, in silent prayer for the oppressed.

(images: screengrab)

Ryan Morgan is a human rights worker in Central America. He tells New Yorkers he’s from Denver, which is true, and other people he’s from New York, which might as well be. He is a fan of FC Barcelona and the Colorado Rockies, and lives on Nat Sherman Classics and iced coffee. His main goal in life is to remind people he meets of Toby Ziegler.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]