Initially, I wasn’t planning on seeing Oppenheimer, because I’m leery of any media portraying this time period in history. I studied East Asian history in college in an attempt to better understand my heritage, and came away from it with a greater understanding of the role Asian history plays in the world stage. This was a history that got lost during the bulk of my American education, replaced by repetitive patriotism that I gained absolutely nothing from.

Indeed, it took until my senior thesis course to learn that Emperor Hirohito was willing to surrender before the first bomb dropped, and the U.S. Government was aware of this. And in a photography history course I took prior to my thesis, I saw images taken of the “nuclear shadow imprints” in Hiroshima: haunting silhouettes of human bodies created by the heat of the blast. Throughout my studies, I learned about how Japan changed after the war, how civilians responded, and how the world at large began to shift its perspective of this powerful island nation. Everything I learned left me with a strange, conflicted, and ultimately sour taste in my mouth.

Many debates have been had regarding the “necessity” of the bomb, and this isn’t an article where I’ll be joining in. My stance regarding Asian history has always been that it needs to be better understood in general, or else orientalist perspectives will continue to be ignorantly proliferated, as they still are.

Therefore, when I heard that a movie was being made about the guy who made the atomic bomb—and by a beloved British/American director, no less—I immediately jumped to conclusions. Yet, I bit my tongue after reading various positive reviews (most of all our own Rachel Leishman’s) and doing my own research, and in the end, I decided to watch the film myself.

And, ultimately, I’m incredibly glad that I did. Oppenheimer isn’t the film I thought it would be—nor is the film itself the root of the polarized reaction to it.

Anachronism and execution

Christopher Nolan has gone on record stating that the film’s tunnel-vision is intentional, as it’s supposed to be almost entirely from Oppenheimer’s perspective. To the initial skeptic, like myself, this might seem like a cop-out, an excuse not to think about the ramifications of everything Oppenheimer said and did. More to the point, I was hoping not to see a movie glorifying this man.

However, the juxtaposition between his perspective and the consequences of his decisions was done beautifully. They allowed for a clear observation of who this man was, and how the events that transpired occurred because of who he was. And we learned, as a result, that Oppenheimer was neither a hero nor a villain; he was a complicated, overly-egotistical, short-sighted, somewhat naive-despite-his-education nerd, who had good intentions yet lacked the foresight to properly judge the ramifications of his actions. This ran the gamut from having destructive affairs to, of course, spearheading the creation of the atomic bomb.

There was care here in recreating this man’s life, deliberate care that neither lauded him nor degraded him fully on either side. The audience is swept up easily in his vision, his zeal for his research, just as much as we are uncomfortably sat in the room with him watching him say and do truly baffling things.

Ultimately, I was thoroughly impressed with Nolan’s portrayal of such a polarizing figure. During my studies, we were constantly told not to anachronize history—in other words, not view historical subjects strictly through a modern lens, with modern thinking, hard as it may be. Though we might be tempted to do so, we ultimately lose a lot of the truth of the era by refusing to see it for what it was, and we stand to gain more by allowing ourselves to fully understand every facet of an era, warts and all. It was therefore imperative that Oppenheimer be portrayed in a way that was only biased towards accuracy, and for all intents in purposes, this was done superbly.

As a result, the rest of the movie carries with it the beautiful spirit of a historical movie done right: (mostly) avoiding anachronism and avoiding sensationalist bias. We got the full truth of what immediately happened within the sphere we were given, which carried a lot of ego and tension, all of which was paid off with a nationalistic horror show that, in the end, ultimately punished Oppenheimer.

All of which is to say that I think Oppenheimer‘s narrow focus was a wise directorial choice. When discussing history, it becomes difficult to properly articulate the weight of a particular topic when it branches off in too many directions. As undergrads, we were forced to choose a regional path and take courses within that region in order to graduate, which resulted in me taking a mixture of both niche courses (“Women in China’s Long 20th Century”) and general courses (“The Making of Modern East Asia”). The general courses painted a vague, yet necessary picture, while the niche courses filled out my knowledge and overall gave me a well-rounded, well-informed perspective of my chosen region.

Does this mean the criticisms lodged against Oppenheimer are unfounded? Not at all. The modern state of leftist politicking has many of us wary of films like this, as we’re led to believe they’ll take an American Sniper approach to such dark topics. Like I said earlier, I certainly fell in this camp prior to watching the film. Now, however, I don’t think the movie itself is at fault here … for the most part.

The true merit of history, all sides of it

Walking away from Oppenheimer, my only critique of the film was that its third act dragged on unnecessarily long. The resolution of the second act—the disturbing zeal of American patriotism, coupled with the horrified reactions of everyone else, Oppenheimer included—wrapped itself up a touch too quickly for my liking. I’ve meditated on the trial scenes and, ultimately, understand why Nolan wanted to include them, yet narratively, I still think they fell flat.

In my opinion, this was the best opportunity for the film to focus more on the ramifications on the bomb, both through Oppenheimer’s eyes and from that black-and-white objectivist perspective the film dually took. Moreover, he and those he associated with continued to speak and write on the bomb following the war (as you can read about in this excellent essay, from a Japanese scholar’s perspective), and I would have easily preferred to see more scenes about those endeavors.

However, therein lies the crux of this movie’s “controversial” approach: This, really and truly, is a movie about Oppenheimer’s point of view, and while Oppenheimer regretted the blood on his hands, he never expressed “enough” shame to merit an extended portion of the film dedicated towards his remorse. Indeed, the Oppenheimer we got was a largely self-interested man with tunnel-vision, and the film did a fantastic job representing this. It set out to portray the accurate historical events surrounding such a polarizing figure, and it did better than most historical films out there.

And that, there, is the most stark observation I’ve made after seeing Oppenheimer: The culture we live in is a culture that would allow a movie like it to be made, at the expense of other stories during that period that also deserve being told. In an ideal world, we could have a film focused solely on the man who brought about a new form of mass destruction in the world, and it would be balanced squarely amongst other stories from that specific period in history. However, we don’t live in that world. For instance, we don’t have big blockbuster films about the people who lived downwind of Los Alamos, many of whom were Indigenous communities who were affected by the radiation.

Nor do we live in a culture that places much stock in genuine Japanese history, beyond a very western, orientalist fetishization. There are many wonderful, heartbreaking films and pieces of media from Japanese perspectives that illustrate, both realistically and artistically, the aftermath of the bombs. Yet these films seldom reach the same level of acclaim and attention in the west that films like Oppenheimer do.

And while this might be something of a simple answer, I ultimately chalk this up to how history is treated in the west—specifically America, as this is where I’m from and where I was educated, and I can’t speak for other nations. History is often treated as one of the most boring and stale subjects in the humanities and social sciences, yet the reason I was drawn to history was because it’s a discipline that gorgeously coalesces all facets of the social sciences. It gives you the world at your fingertips and teaches you to absorb the mistakes and beauties of the past with a clearheaded perspective that allows you to see the modern world in a new light: as a world that’s a product of many, many facets, all of which are necessary to learn in order to fully understand the world we live in.

So, with all that said, I deeply admire Oppenheimer for what it accomplished, and I do not think it’s quite the bogeyman that people make it out to be. Instead, I think the true bogeyman is the lack of proper education we’re given regarding well-rounded histories, and how institutions in power will often use history less as an opportunity to remind us of our humanity and more as a means of propagating harmful ideals.

It shouldn’t just be the uniquely “American” stories that get the most funding, the most attention, the most press. I’d love to see more historical movies in the “style” of Oppenheimer, focused on other narratives that deserve to be told. Hopefully, this is something we can see more of in the near future. Until then, I’m glad I saw Oppenheimer; my understanding of this topic has broadened, and it no longer fills me with the despondent dread I used to feel surrounding it.

That’s what I love about history: The more you know, the less powerless you feel, even if the truth can be monstrous.

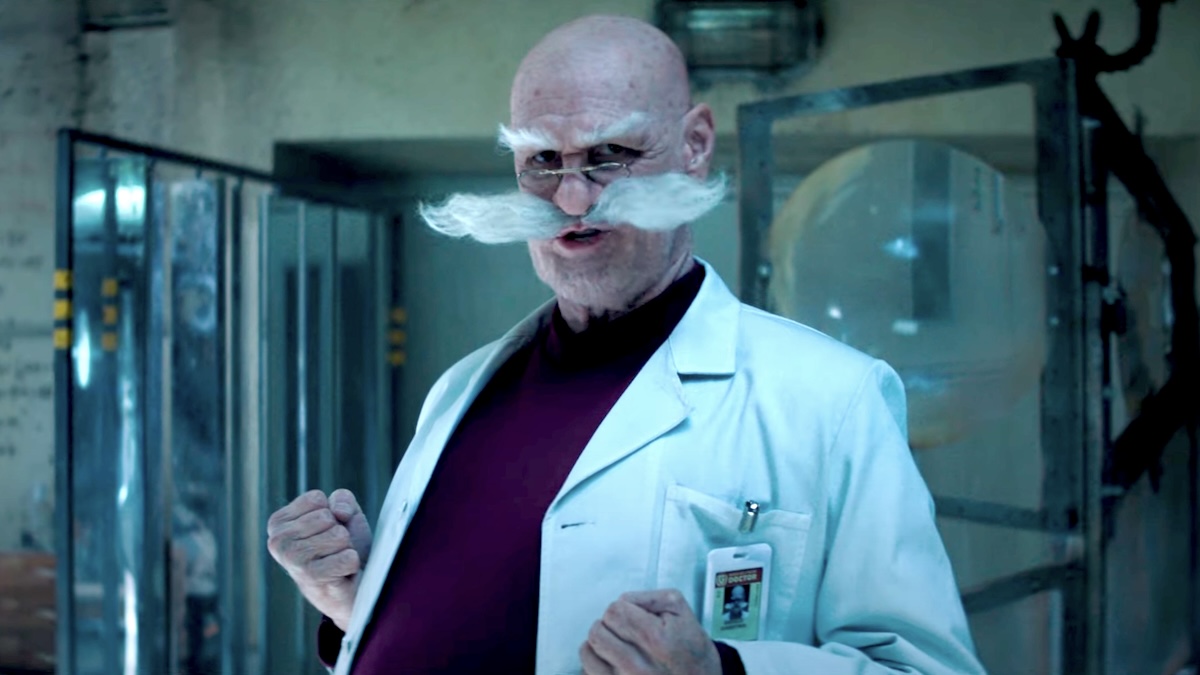

(featured image: Universal Pictures)

Published: Aug 31, 2023 01:50 pm