The Mary Sue is pleased to present strange, beautiful new fiction from Apex Magazine each month. This month’s story, from Apex Magazine’s current issue, is “Requiem, for Solo Cello” by Damien Angelica Walters. Take a look…

I.

The first time I saw you play:

Bach’s Six Suites for Unaccompanied Cello; your chin tucked down; your eyes soft but intense; the fingertips of your left hand deftly pressing into the fingerboard; the bow in your right moving across the strings like a lover’s sensate promise.

Each chord struck a place in my soul, a waiting place of longing, and my self hovered in the spaces between the notes. I didn’t wipe the tears that spilled from my eyes. I couldn’t. Perhaps I should have; I had wings then, and the music was guiding me to flight. Guiding me away.

II.

I waited in the lobby, trying to gather the courage to speak, to tell you how your performance moved me. How silly it seems now as a crowd of young women much like me was in place, all for the same reason, yet I convinced myself I was somehow unique among them all and that you would see it in the set of my jaw and the shimmer in my eyes. I am more, I wanted to tell you. I can be so much more.

You passed by and I smiled. Our gazes met briefly; you looked away first. You took care not to brush my arm, not to brush anyone’s arm, and in that moment, I knew. Human flesh, its softness and warmth, held no draw, cast no spell for you to fall under. You craved only the instrument you could hold, only the music you could create.

(I told myself later this was merely a trick of the light.)

That night, I dreamt my hair was the scroll; my face the pegbox; my neck the fingerboard; my belly the bridge for the strings to arc across; my shape not soft and yielding, but hard and immobile, ready to be brought to life only by your genius, the bow of your touch.

When I woke and opened the case of my own cello, the music seemed pale and inconsequential and the notes disappeared into the air. I wept of ever creating something that would bring an audience to a hush.

III.

Every night you played, I was there, clasping my hands together, breathing in each perfect fifth, marveling at the lines of your body, the precision of your hands. And every time you passed me by, I held your gaze. After days, weeks, months, you finally paused to speak, and my words tangled in my throat. All I could manage was this: “Glissando.” You laughed but your lips formed a smile, a spark danced in your eyes, and you asked me to accompany you for coffee.

I wish I could remember the rest of the evening, what I said, what you said, but it’s hard to remember such things now. Perhaps I don’t want to remember, to see how easily I left my own song and agreed to become yours. The only thing I do remember is that you never asked to hear me play. Not once. Not ever.

IV.

It began this way:

You gathered my hair into elaborate curls, piled them atop my head and pressed your lips to my neck. The touch of your skin against mine locked my vocal cords, but I embraced my newfound silence, felt the power resonate in a way words never could.

Your hands skimmed my sides, carving me with your heat, bending and pushing my waist in, my ribcage and hips out, to remake my shape. Stradivarius would have been in awe of your artistry. My bones shifted, adjusted, remained where you set them. You bound my ankles together for the tail spike, fixing me in place.

Your fingertips danced across my face and my eyes became polished maple. You did not add the decorative inlay, the purfling that would protect me against damage. I chose to think it a particular conceit of yours, something which should not be risked as it might alter the music.

You held me close and whispered words I couldn’t quite hear, but I told myself it was fine, everything was fine, because I could feel the beginning of a melody deep within. Your song, I believed; I believed it with every ounce of my being.

V.

And finally:

You peeled back the skin of my chest and reached into my heart, separated the fibrous strands and plucked them one by one. The pitch was wrong—discordant and fractured and ugly—and I told myself that one day perhaps I’d think it beautiful but I knew better. Your arrangement was neither sonata nor allegro but a liar’s symphony, a mockery of every great concerto, and if you’d not stripped my vocal cords of their ability to vibrate, my limbs of their ability to move, I would’ve given birth to an altissimo in lieu of a scream and put an end to the farce. I would’ve shown you the truth, that you were not the virtuoso you believed yourself to be. Instead, my polished eyes reflected only you, and my neck stretched to maintain the necessary tension.

You thought this music would somehow make you whole, yet you played the same score again and again, your face twisted, your own eyes glazed, as if you knew the tune wasn’t right but lacked the skills to find what you needed in the notes.

VI.

When you gave up, breaking your bow across your thigh and storming away, your vanity wounded, dust became my orchestra and silence, my lament. I ached inside as my limbs struggled to reclaim their silhouette and architecture; I yearned for an allegro of my own, yet one to begin, not as ending.

After days, weeks, months, I plucked the wood from my eyes, breathed my waist out, and reached inside to find the sheet music you left behind. The paper was yellowed, the lines smeared with illegible scrawls, and I ripped them free.

And from the hollow came a clear and perfect C, like a voice in the darkness, and a song began, the music containing chords of such complexity and depth, major and minor triads, tempered yet not imperfect. The notes danced into a crescendo unlike anything I’d ever heard or played before and tears fell from my eyes.

It was Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G as played to perfection by Mischa Maisky; it was The Swan of Tuonela as composed by Jean Sibelius; it was Yo–Yo Ma performing with the New York Philharmonic; it was Jacqueline du Pré’s recording of the Elgar Cello Concerto; it was every harmony, every octave, and every aria that had danced in my dreams and lingered on my tongue. It was all of these things and more. It was mine. It was beautiful.

I was beautiful.

I felt your presence in the shadows and for a moment, I thought you would speak. I hoped for an apology or an explanation, but your silence stretched into nothing at all, and without a backward glance, I gathered my arpeggios and left you there alone with the empty measure of your own composition.

—END—

Please visit Apex Magazine (www.apex-magazine.com) to read more great science fiction, fantasy, and horror.

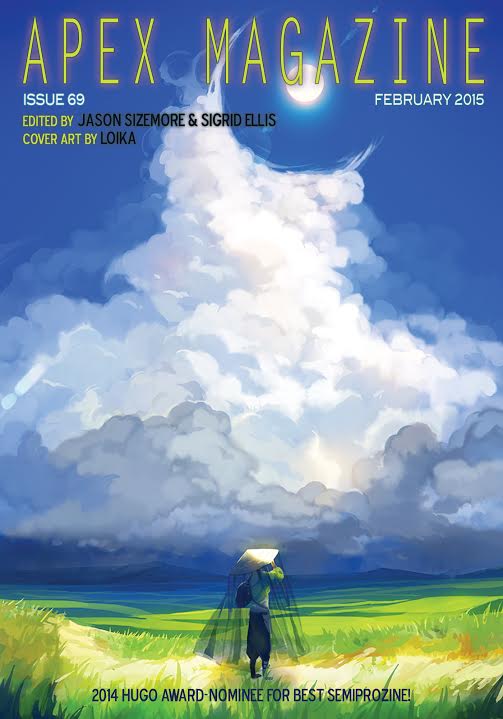

This story is from issue 69 (February, 2015). The issue also features fiction by Lisal L. Hannett (“Heirloom Pieces”), Mary E. Lowd (“Foreknowledge”), Rhoads Brazos (“Inhale”), Susan Jane Bigelow (“The Best Little Cleaning Robot in All of Faerie”), Fran Wilde (“The Topaz Marquise”), and Brian Keene (“A Revolution of One”), poetry by Leslie J. Anderson (“Werewolf’s Aubade”), John Philip Johnson and Salvatore B. Lombard (“Second Mouth”), and Michelle Muenzler (“what we eat when”), author interview with Brian Keene and cover artist interview with Loika, and nonfiction by Ed Grabianowski (“Supposedly True (but Probably Not, and That’s OK) Weird Tales”)

Each issue is free on our website, but Apex sells nicely formatted eBook editions for $2.99 that contains exclusive content.

You can find more Apex Magazine stories on The Mary Sue here.

Published: Feb 3, 2015 06:00 pm