‘They Called Us Girls’: The Narrowing & Broadening of a Writer

And what inspired her to write this book when she did.

I’ve spent the last decade creating a book about women who decided they wanted to work in jobs that were, by the standards of their day, “men’s” jobs. I interviewed the women when they were in their 80s and 90s and asked them to tell me about their lives and what fueled their unconventional ambition.

In the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, when these women began their careers, sex discrimination was legal. So was discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion and national origin. This was a decade or two before major civil rights legislation passed in Congress. Women were expected to be caretakers of the home, where their supposed feminine qualities would blossom. But the women in my book knew this would not be a fulfilling life for them. They wanted to work outside the home, in professions that men had dominated from the beginning.

Today, we don’t find it strange that a woman excels in medicine, law, science or other such fields. But when I was a girl, it was remarkable. I felt awe and wonder just knowing such women existed, and writing the book meant rediscovering those feelings.

Let’s go back to the late 1950s. Sputnik was a Soviet satellite, not the name of a Russian vaccine, and its launch turned up the heat of the Cold War. Telephones were black and clunky, and fixed in one place. Color television had not yet arrived in American households. My family had a black and white set where I watched shows like Leave It to Beaver. The mother on the show, June Cleaver, in her pearls and high heels, was an exaggeration, but not an impossible stretch, given what I saw in my neighborhood. Yet I knew that some women, somewhere, were different. My father was a lawyer and a handful of women had been his classmates in law school. These real women intrigued me, even more than fictional characters on TV.

Fifty years later, when I started the book, I was a lawyer. I began law school in the 1970s, when women surged into graduate school in unprecedented numbers. Even with all my experience with other lawyers and judges, I had met very few women of the older generation, the ones I had been curious about when I was a kid. Fueled by my childhood sense of wonder, I decided to meet them while I could.

Growing up means leaving childhood behind, but now I wanted to be in touch with my younger self. To remember how I was when I was a girl, I used some of the techniques my fiction writer friends use when they imagine a character in a novel. I closed my eyes and pretended I was an eight-year-old girl, simultaneously naïve and questioning. In my head I reenacted some of the things I used to do—hula hoop, dodge ball, riding my first blue bike. I dredged up long ago conversations with my parents. I became a character in the stories I would tell about the women’s lives, both as I was then and as I had become in the years since.

Of course, the world is broader and more complex than what I knew when I was eight. I wanted to capture that complexity in the life stories I told. One woman grew up in great poverty, others in families that aspired to be middle-class. Some women grew up with two parents, others only one, while one woman lost both parents in the aftermath of World War II. Several were immigrants, or their parents were. Some families were religious, others not. Race was a factor, too. One Black woman went South early in her career, where Jim Crow laws were strictly enforced. A Latina woman experienced more subtle discrimination in the North. These women were diverse in their work and personal experience, but they shared an unconventional ambition. To find where that ambition came from and how it played out for them, I had to both narrow myself into the thinking of an eight-year-old girl and expand myself in order to write about the diversity of women’s experiences.

—

They Called Us Girls

In mid-twentieth-century America, women faced a paradox. Thanks to their efforts, World War II production had been robust, and in the peace that followed, more women worked outside the home than ever before, even dominating some professions. Yet, the culture, from politicians to corporations to television shows, portrayed the ideal woman as a housewife. Many women happily assumed that role, but a small segment bucked the tide—women who wanted to use their talents differently, in jobs that had always been reserved for men.

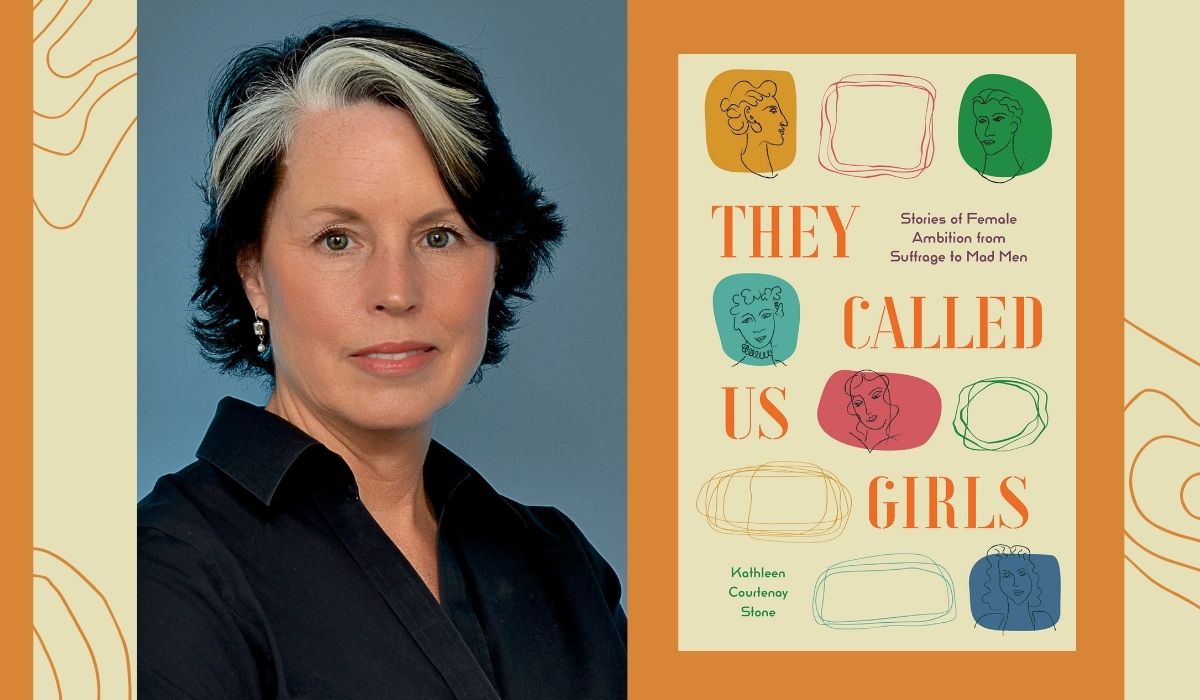

In They Called Us Girls: Stories of Female Ambition From Suffrage to Mad Men, author Kathleen Courtenay Stone meets seven of these unconventional women. In insightful, personalized portraits that span a half-century, Kathleen weaves stories of female ambition, uncovering the families, teachers, mentors, and historical events that led to unexpected paths. What inspired these women, and what can they teach women and girls today?

They Called Us Girls released March 1.

(image: Cynren Press and Alyssa Shotwell)

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]