Backlash to Queen and Slim Reviews Highlights the Importance of Black Female Critics

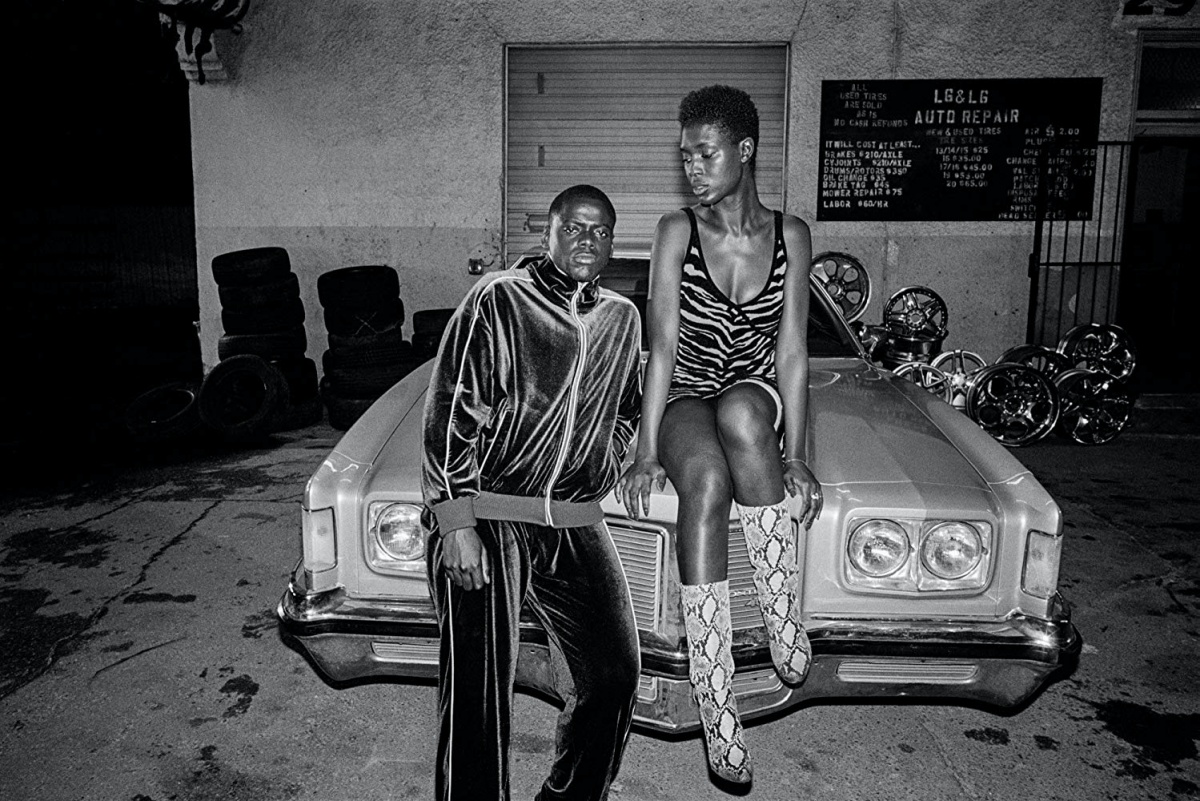

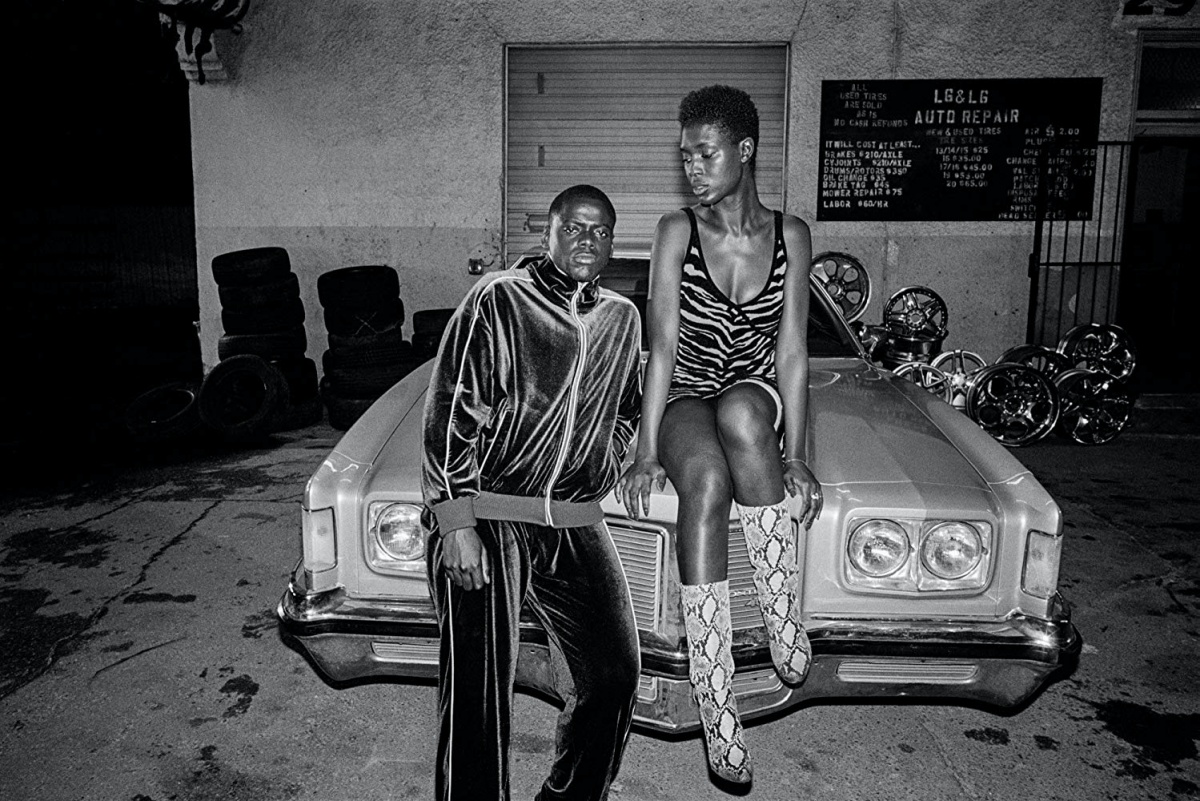

One of the most interesting things to come out of the 2019 film Queen & Slim, directed by Melina Matsoukas and starring Daniel Kaluuya and Jodie Turner-Smith, is the discourse among Black critics, especially among fellow Black women who have had mixed reactions to the film.

In the film, the titular Queen and Slim, after killing a police officer during a traffic stop, go on the run and become folk heroes in an era of police brutality. As I’ve looked on my timeline to the Black women who I respect in the industry, I saw that many were giving their opinion, both negative and positive, but the negative reviews were attracting a certain level of pushback for “talking badly” about the film.

Film critic and TMS contributor Valerie Complex brought a bunch of these screenshotted tweets together to highlight the vitriol that was being targeted towards critics:

Ppl should be free to critique art without the pressures of protecting ppl just bc we share the same skin color. Stop this crap now pic.twitter.com/m2hFK69rtf

— 🔥🖼Valerie Complex (@ValerieComplex) November 30, 2019

First of all, Black critics, especially Black female critics, are not going through the labor of trying to get access, get screeners, and make waves in this industry through hard work and inconsistent pay, to be asked to shell out complements for the sake of a studio industry that doesn’t give them regular access to films outside of the Black Beat. That’s number one.

Secondly, one of the things that Black critics have always had to deal with is this perspective that we will monolithically gravitate towards Black films, that we have no other interests outside of that, and that when we do watch Black movies, we are going to universally praise them. Not only is this straight-up disrespectful, but it completely flattens Black identity into a monolithic experience that does a disservice to the perspective we bring to the whole industry when given a platform.

As lovers of film, television, and any kind of pop culture, we are required by just sheer numbers to know and have exposure to things outside of our own race and ethnicity. When I took film courses and literature courses, I didn’t get handed the all-Black art menu while my white peers got to hang out in the land of De Palma and Homer. We bring a broad knowledge to the table and also the lived experience of being Black people in America (or any place where police brutality targets Black people).

More so, we are allowed to raise the bar of what we expect from Black cinema, and no one, not even fellow Black people, should expect our opinions to be in line with anyone just because of our race. Can we debate and disagree based on our opinions? Absolutely, but I reject the idea that it’s alright to call a Black woman “Uncle Tom” for saying that the film fails on certain levels.

Words mean things, and while I understand the desire to protect Black cinema and allow it to be imperfect in the same way white cinema has been, that means allowing people to dislike it for valid reasons without turning it into a war zone. We feel like we have to be so invested in every single Black product because we’re afraid it’ll be taken away if it doesn’t do well, but that creates an unfair standard for everyone—actors, writers, directors, and critics.

We are not a monolith, and our film opinions shouldn’t be weaponized against us.

Also, give Black critics more access to non-Black movies. We want to see Little Women too, damn it.

(image: Universal Pictures)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]