Banned Book Sales Skyrocketing Isn’t the Win People Think It Is

What happens when the giving stops?

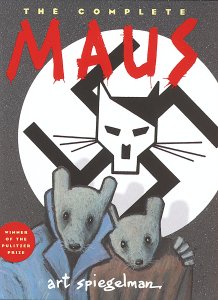

Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel memoir Maus remains in the news cycle because it makes people feel very angry, or very (for lack of a better word) fuzzy. The anger comes from those who are rightfully horrified to learn of recent censorship efforts by those seeking to downplay the holocaust to preteens. The “fuzzy feeling” comes from those celebrating Maus‘ climb back into the bestsellers list.

Some comic book shops are straight-up giving away copies of the Pulitzer Prize-winning work. I understand the knee-jerk reaction to see this as a win or feel like we “pwnd” neo-Nazi’s and conservative parents, but this sales boost will not fix the problem. Also, it represents tiny fraction of what has happened in the recent wave of censorship efforts against books, schools, and libraries.

Before I go any further, authors and smaller booksellers get a pass. They weren’t the targets and are trying to find the good in a never-ending sea of bad. Some, like author George M. Johnson, take these bans as an opportunity to speak up and directly to the youth targeted.

In addition to participating in larger segments featuring many voices affected by these bans, Johnson has also taken their advocacy into long-form interview spaces like Marc Lamont Hill’s show. Johnson explained, “When we have queer writing in YA, a lot of it is fictionalized, so people get to say, ‘Oh wow, that would be really sad if that happened to someone.’ Because I wrote a truthful story, people can’t deny the truth. Realistically this is just a fight against the truth.”

All the unnamed authors left behind

Regardless of political leanings, outrage is social currency. Even the short-term sales boost and visibility don’t affect all authors equally, once these bans hit. In many high-profile book censorship circumstances, lawmakers and administrators pull multiple books from the shelves or place them “under review.” Many people only hear about the most recognized titles or sensational stories. This is not accusatory—if you look at our coverage on it the last few months, I have danced this line, too.

Part of the reason is that these lists are so extensive. In Texas, the state is reviewing (in the process of removing) over 800 books. Instead of listing them all, we need to name some and link to the complete list. Then, we can move to the context and why people should care about all the books. Not everybody has heard of every book, so news stories on these subjects often wind up with nods to marginalized authors sprinkled in among the high-profile titles (often by cis-white authors). This has been especially apparent in the cases like those of late, where titles are under attack for so-called “critical race theory,” “reverse racism,” or something along the lines of “normalizing harmful behavior.”

This creates a feedback loop, and most authors whose books end up on a banned or censored list, regardless of background, will not get a significant boost in sales, even if those sales could balance out the harm.

The end game for the bans

The urge to out-fundraise works in politics more often than it should but doesn’t work with most other social problems. Opening pocketbooks helps, but money alone won’t fix these problems. People will donate to such and such organizations and think that will lead to the issue will being resolved.

From advocating for literally setting books on fire to suggesting replacing emptying shelves with extra copies of the Bible, those pursuing this censorship aren’t even half subtle about the goal. When these books are banned and censored, young people will not see themselves represented in their community and may think reading is not for them or people like them. In the case of historical books, people will spread ignorant, whitewashed versions of longstanding issues.

When Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue is banned from school libraries (assuming any LGBT fiction goes under the radar), children who express gender outside “the norm” don’t get to see themselves or their families. The goal of these bans is to negate access, limit the imagination, and assert a limited framework of cultural dominance. In the case of Maus‘ removal from a Tennessee district’s 8th-grade curriculum, even if someone handed every 8th-grade child a copy of this book, they will not have a dedicated space (like a classroom with a trained facilitator, a.k.a. a teacher) to discuss its themes, historical context, and metaphors.

(Pantheon Books)

Once a book is banned, it’s a domino effect of consequences that can’t be out-fundraised. Authors of these banned books will not be invited to speaking events, signings, etc., because their book, against all odds, was published but only made available to those with money, not for the public good. This ripples further into library programming discussions, as well as book displays, and the effects are immeasurable.

(image: ChildrenNatureNetwork)

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]