Novels set in World War II are often the most harrowing and heartbreaking stories that are somehow interlaced with hope. The books I decided to feature on this list showcase a variety of themes—from searches for lost treasures to the lengths and beauty of human kindness. The latter, especially to me, is what makes these stories essential and worth the read.

[Note: For this list, I focused in on books set in the European Theatre during the war—this was, of course, a global conflict that touched many nations and people. There are fantastic novels set from other perspectives—The Kitchen God’s Wife, Shanghai Girls, and An Artist of the Floating World are all excellent places to start.]

All the Light We Cannot See

Published in 2014, All the Light We Cannot See won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the 2015 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, on top of outstanding reviews and a recommendation from none other than former President Obama himself. The novel is structured in a nonlinear format and primarily shifts between the two perspectives of its main leads: Marie-Laure Leblanc, a French girl who is blind and the daughter of the master locksmith at the Museum of Natural History; and Werner Pfennig, a smart German boy who ends up in military school for his talent at working on radios. The novel is a slow burn that builds up to the Battle of Saint-Malo, all while interspersing the arc of its main villain, Sergeant Major Reinhold von Rumpel, a Nazi in search of a legendary gem that’s said to give its holder immortality. Before the outbreak of the war in Paris, the director of the Museum of Natural History had procured decoys for the gem and had distributed it among his most trusted confidantes, with none of them knowing who had the original. One of these confidantes was Marie’s father.

All the Light We Cannot See paints a beautiful portrait of Saint-Malo and showcases the reverberating effects of a single act of kindness. Although slowly paced, it keeps you on the edge of your seat and leaves you wanting to stay up and continue reading just to see how Marie and Werner will cross paths.

Atonement

If you’ve seen and loved the 2007 adaptation starring Keira Knightley, James McAvoy, and Saoirse Ronan, then you must read the book. Set in three time periods—namely, 1935 England, Second World War England and France, and present-day England—this 2001 novel by Ian McEwan was shortlisted for the 2001 Booker Prize for fiction and also won the 2002 National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction. Much like the adaptation, it follows Cecilia Tallis, an upper-class girl, and their family housekeeper’s son, Robbie, through tumultuous years after Cecilia’s sister makes the mistake of accusing Robbie of a crime he did not commit. Spoiler alert: the book ends on a similar note as the film but in the form of a diary entry as a sort of postscript, which, if you ask me, is more heartbreaking than how it’s shown in the adaptation. As a side note, if you’ve just finished reading this and are in severe pain, I highly recommend going through the adaptation’s Letterboxd reviews. I’m convinced they’re the best reviews section of people collectively grieving and losing their minds on the site.

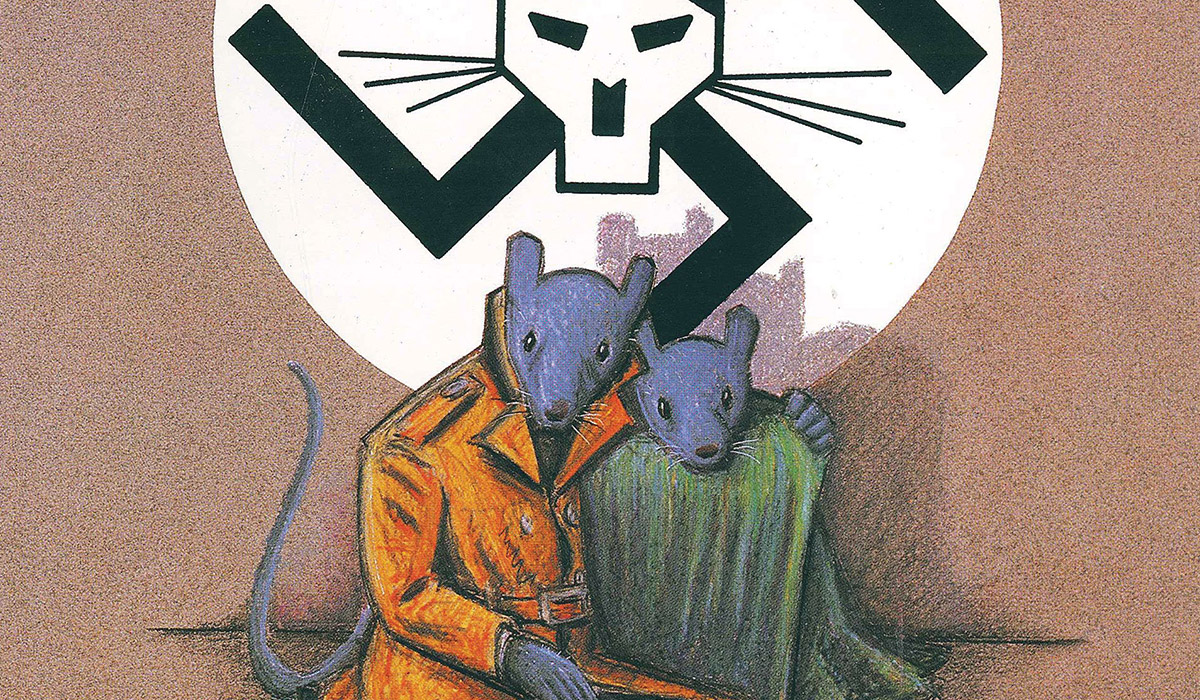

Maus

Maus is a graphic novel serialized from the 1980s until 1991 and depicts its cartoonist Art Spiegelman interviewing his father about his experiences as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. The two-part novel also delves into generational trauma. It famously depicts its characters as animals, with the Jewish people as mice, the Germans as cats, the Americans as dogs, and the British as fish. On the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day earlier this year, the book was shamefully banned by a Tennessee School Board. Its members argued that the novels contain “inappropriate words” as well as nudity and “graphic depictions of violence.” In a report from The New York Times, one board member said on record, “It looks like the entire curriculum is developed to normalize sexuality, normalize nudity and normalize vulgar language. I think we need to re-look at the entire curriculum.”

This all, of course, defeats the point. As Spiegelman himself put in an interview with The New York Times, the Tennessee School Board was essentially asking, “Why can’t they teach a nicer Holocaust?”

Schindler’s Ark

Before it was a beloved, black-and-white Steven Spielberg classic, the story detailing the life of the great—but flawed, because he wasn’t a saint—Oskar Schindler was first a novel written by Thomas Keneally. Although Schindler himself is very much a real person, the book itself and its central character are works of fiction that happen to be based on real events. In several interviews, Keneally has talked about how the book was actually inspired by a story told to him by a Holocaust survivor named Poldek Pfefferberg, also known as Leopold Page. During his winning speech, after winning the Booker Prize, Keneally personally thanked Pfefferberg and said, “‘Although I think that in all good conscience I think the book is a literary work and a novel, it is necessary to thank the people, the characters who are actually alive. One of the characters is a luggage merchant from Los Angeles—Poldek Pfefferberg or Leopold Page—not only could I recommend his merchandise but he was the man who gave me the story.”

The story of how Pfefferberg fulfilled his promise to Schindler himself to get the story out is deserving of a novel of its own, actually. He’d tried getting into contact with writers and screenwriters on countless occasions to work on the story of unlikely hero Schindler and his efforts to save Polish Jews before meeting Keneally, who’d come into his shop in Beverly Hills to look for a new briefcase. When he found out that Keneally was actually a novelist, he recounts telling Keneally, “I have a great story for you.” He was able to convince the writer to work on the book after showing his extensive files on Schindler and the rest, as they say, is history.

Pfefferberg was Number 173 on “Schindler’s list.”

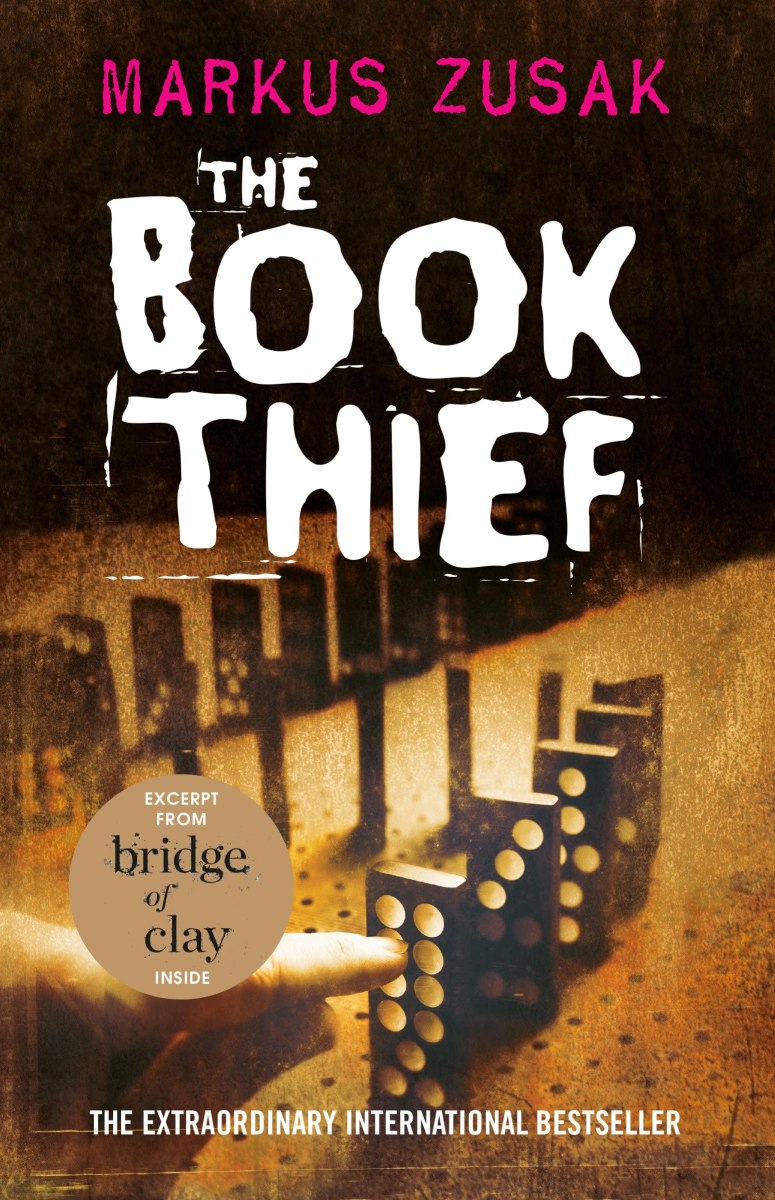

The Book Thief

Often hailed as one of the best Young Adult Books of All Time, The Book Thief opens in February 1938 and is narrated by none other than Death itself. It recounts the story of Liesel Meminger and her adoptive German family during the war and her quest to “borrow” books and share them with Max, a Jewish refugee whom her family helps hide in their basement. The Book Thief is probably one of the first novels I read that was set during World War II as a kid and although I’ve deliberately avoided rereading it since then, I still remember bringing my copy everywhere I went, the tears I cried for Liesel, Max, and Rudy (We don’t talk about Rudy here), and that distinct feeling of pain and hope when I closed my book that stays with me even after all these years later.

(featured image: Paramount)

Published: Jul 22, 2022 03:55 pm