Last month, Tommy Altmann, a Republican congressional candidate in Virginia, sued Barnes and Noble because the bookstore was selling Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe and A Court of Mist and Fury by Sarah J. Maas. Now, Altmann and his attorney, Tim Anderson, are escalating their attack on queer-friendly literature by suing Maia Kobabe and Oni Press, the author and publisher, respectively, of Gender Queer. Why? Because of Virginia’s obscenity laws, Altmann and Anderson claim that that Gender Queer is “obscene for unrestricted viewing by minors.”

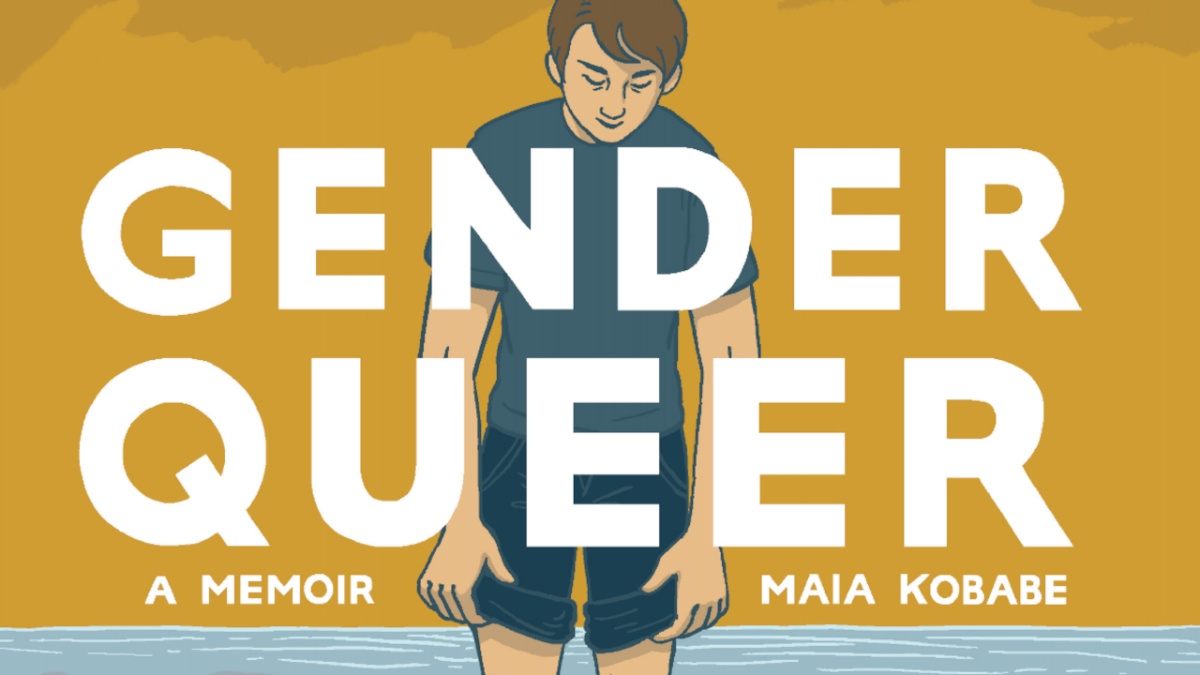

Gender Queer is Kobabe’s graphic memoir about growing up in Northern California and exploring eir gender and sexuality. It’s an honest and frank account of issues like gender identity, menstruation, masturbation, and sex. It normalizes common experiences that many people think are unique to them and shameful to talk about. In short, it’s exactly the kind of book that readers, queer or straight, desperately need to have access to.

Luckily, Oni Press’s lawyers are confident that the lawsuit is unfounded, stating that the lawsuit violates the First Amendment and fails to take into account the graphic novel as a whole. In classifying the work as obscenity, Anderson and Altmann have cherry-picked a few pages out of a 240-page memoir and mischaracterized the book as something that’s aimed at children, when, in reality, it’s written for adults.

However, there are a few alarming implications of this lawsuit.

First off, the U.S. Supreme Court is now a radicalized and unabashedly partisan tool of the religious right, and with its recent rulings overturning abortion rights and allowing prayer in public schools, SCOTUS’s conservative majority has demonstrated that it couldn’t care less about the constitution. If this case, or another one like it, were to make it to SCOTUS, the ruling could be disastrous for authors.

Secondly, as queer novelist Malinda Lo points out, many writers’ contracts now come with an indemnity clause, which holds an author liable for lawsuits brought against their publishers.

As writer Cory Doctorow recently explained, these indemnity clauses can saddle a writer with life-changing debt while the publisher walks away unscathed.

One of the clauses in this contract [for a 2009 magazine article] required me to indemnify the publisher against all claims, including those they settled without consulting me. In other words, if some crank emailed this magazine — which was distributed in dozens of countries around the world — and insisted I’d wronged them and demanded a million dollars in compensation, the magazine could pay them a million bucks and then send me the bill, without ever consulting me, irrespective of the merits of the complaint.

We don’t know the details of Kobabe’s contract with Oni, but the prevalence of indemnity clauses, combined with bigots flinging lawsuits around like confetti, creates an extremely hostile environment for marginalized writers.

Finally, if these types of lawsuits gain traction, publishers may choose to simply avoid taking the risk of publishing works that might be targeted for lawsuits or banned in certain states. Remember that most presses are for-profit ventures that won’t publish works unless they know they’ll recoup their losses. If you’re angry about this, go get yourself a copy Gender Queer right now. It’s funny, tender, enjoyable, and relatable. Screw Tommy Altmann, screw bigots with too much time on their hands, and long live queer comics.

(featured image: Oni Press)

Published: Jul 8, 2022 02:47 pm