**Spoilers for season 5 of Bojack Horseman**

Bojack Horseman has always been one of the most emotionally taxing shows on television, with each season somehow managing to be darker than the last. While, arguably, no single episode in the newly released fifth season may be as devastating as season 4’s heart-shattering “Time’s Arrow,” the season as a whole does succeed in finding new depths of darkness.

This season dives into some deep subjects, from Princess Carolyn’s struggle to adopt a child to Todd’s asexuality to Bojack’s depression and addiction. In true Bojack style, the show undercuts a lot of the heaviness with extreme, sometimes surreal visual gags, which only ends up making the material that much more devastating.

But the most upsetting element this season might be the way the show explores the issues behind the #MeToo movement, issues like sexual assault and workplace harassment. A lot of shows and films have explored these issues over the last year. Some (including Netflix’s own Glow) have done so incredibly well. But I don’t think any show or movie released in the wake of the movement has addressed these issues as well as Bojack. And that’s because Bojack Horseman isn’t afraid to be messy. This isn’t a show that has clear heroes or winners or moral compasses.

Bojack had already touched on issues of sexual assault and other forms of misconduct with season two’s “New Mexico incident” (which still haunts Bojack in season 5) or its spot-on Bill Cosby-figure takedown in “Hank After Dark”. But this season’s depiction of the issues is different in how comprehensive it is. It doesn’t just look at one angle of the assault, harassment, marginalization and otherwise mistreatment of women. It takes on all of it–both the individual and systemic forms of sexual misconduct, how they blend together and inform one another, how everyone is affected, and how nearly everyone is, in some way, complicit in the continuation of these systems of abuse.

First, there’s Gina (Stephanie Beatriz), Bojack’s costar and eventual girlfriend. Her career is a multi-decade string of unsuccessful, and from the sound of it, just plain bad shows, none of which have even gotten a second season. But the work is steady, as a 39-year-old woman in Hollywood, she’s grateful for that. She’s willing to keep her head down and not complain about anything, even the frequent objectification that comes with the poorly written, male gaze-driven work she’s given.

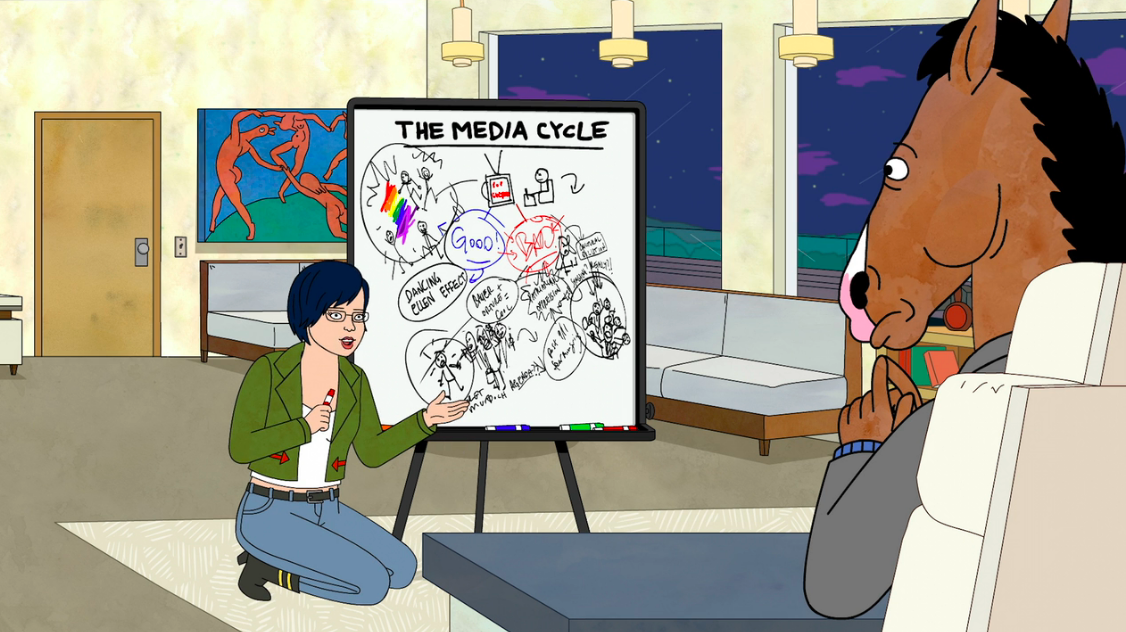

In the episode “Bojack the Male Feminist,” the show tackles the endless redemption cycle of male celebrities like Mark Wahlberg and Mel Gibson, as well as the shallowness of lip service male allyship. When Bojack is declared a feminist hero for doing the bare minimum of saying “Don’t choke women” (and then getting cut off before he can add a “But…”), Diane is tasked with making him more informed. Giving him what are essentially lessons in wokeness is mutually beneficial, since by Cyranoing her words into Bojack’s mouth, Diane can get her message across without being attacked or undermined or dismissed as “shrill.” As Bojack says, “It turns out, the problem with feminism all along was it just wasn’t men doing it.”

For Bojack, the benefit is obvious, as he gets to be celebrated as a hero without actually investing any energy into the cause he’s so casually championing. It’s fun for him, which is, in turn, infuriating for Diane. “Being a woman is not a hobby or a pet interest of mine. You get to drop in and play Joss Whedon and everybody cheers. But when you move onto your next thing, I’m still here,” she tells him.

The most Diane can actually manage to do is to break through just enough to make Bojack realize he can’t accomplish what Diane can, and he convinces her to join his show, Philbert, as a consulting producer. That way, she can have firsthand input on the things she tried to teach Bojack about: the media’s tendency to glamorize and normalize destructive behavior, or how depicting toxic masculinity is not the same as subverting it. But even that small win is quickly crushed when the showrunner tells her her job is to stay quiet and be a name in the credits that makes people feel good about watching a show a woman worked on.

What sets Bojack Horseman apart is how deep it goes in exploring not just these individual experiences, but the levels of complicity every character engages in. Princess Carolyn is the most obvious, as she’ll do and say and cover up pretty much anything to protect Bojack and her career as his manager.

Gina is the epitome of the “imperfect victim.” She won’t speak out against the objectification in her industry because it allows her to keep getting work. She also refuses to reveal (or allow Bojack to reveal) the assault she experiences on set during Bojack’s drug-fueled delirium. And she has valid reasons for that. She is experiencing her first bit of professional success and doesn’t want to forever be known as the woman who got strangled by Bojack Horseman.

Are those reasons enough? Does she have some sort of responsibility to speak out about these things? Or at least to stop perpetuating and profiting from these cycles of marginalization and abuse? These aren’t questions the show tries to answer, but it’s also clear it’s not judging anyone’s choices.

Even Diane, who’s dedicated herself to calling out misogyny and holding abusers and their enablers accountable, has to come to terms with the fact that while she, like everyone else, has spent years protecting Bojack from himself, there have been others that needed protection from him more.

We are repeatedly told this season that good and bad are imaginary categories. In Bojack’s words, “We’re all terrible, so therefore we’re all okay.” Diane puts it as “There’s no such thing as bad guys or good guys … All we can do is try to do less bad stuff and more good stuff.”

The season ends with Bojack entering rehab, which isn’t redemption in itself, but it’s possibly the most important step that direction that he’s ever taken. After a full season of watching characters benefit from manufactured, unearned redemption, it does feel like real growth, even if we have no idea how it will end up.

(images: Netflix)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Sep 19, 2018 12:00 pm