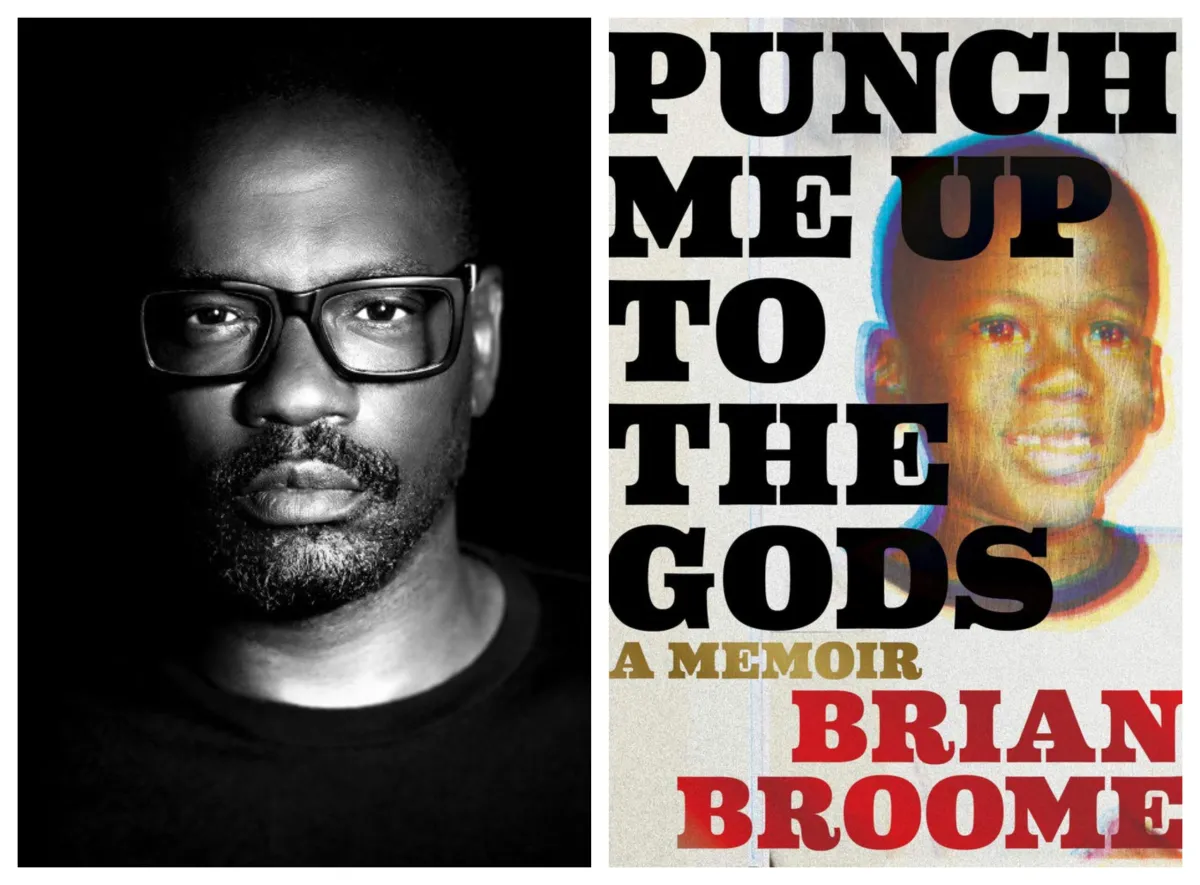

Brian Broome’s memoir Punch Me Up to the Gods is one of the most stunning debuts I’ve had the pleasure of reading.

Broome’s voice captures you instantly, drawing your attention into the beautiful, poignant, and often painful intricacies of Black adolescence—most particularly, Broome’s adolescence as a dark-skinned, gay Black boy in the 1980s. With a beautiful introduction by poet Yona Harvey, Punch Me Up to the Gods is a novel that not only examines Black boyhood but celebrates it, embodying the heart of Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem “We Real Cool” in every page.

One of the things that struck me most while reading this novel is how much I could empathize with the experiences that Broome describes—the cultural weights, the generational trauma, and the nuances of the Black experience. Broome’s book doesn’t shy away from its heaviness, but threading within all of that is a beautiful introspection and healing that truly grabs at the reader and sticks with them long after they’ve finished the book.

The Mary Sue got the lucky opportunity to talk to Broome about Punch Me Up to the Gods, his writing journey, and why it’s so important to have these loving and thoughtful “odes to Black boyhood.” Check out the interview below!

The Mary Sue: From the very first page, your voice leaps out with poignant, memorable fervor. When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer?

Brian Broome: When I was a boy, I used to write all the time. At first, I wrote in a diary that my sister gave me. Then I moved on to journaling about my days in notebooks. At that time, I think I maybe wanted to be a writer even though I didn’t really know what that meant.

But the desire to write faded after people told me that writing was for girls and that they thought it was weird that I was doing it. After I found drugs and alcohol, it was really over. I didn’t write a word. I only started again when I went to rehab. It was like I picked up right where I left off. So maybe now I’m realizing again that I want to be a writer.

TMS: What was the writing process like for Punch Me Up to the Gods? What first inspired you to pen a memoir?

Broome: Writing this book involved a lot of deep breathing. Just closing my eyes and trying to remember specific details as well as how I felt at particular times in my life. A few of the stories were written while I was still in rehab. When I got out, I sat in my home by the light of a computer monitor and played endless music from different periods in my life. Music helped a great deal when I was writing some of the more fraught stories. I’m not the type of person who is able to write in coffee shops or any other public setting.

When I had all these stories compiled, I still really didn’t know they were going to result in a memoir until I handed them to my editor, Rakia Clark, and she said, “This is a memoir.”

I had just been writing stories that I thought were significant events in my life. She helped me to see them as such. The stories didn’t really become a memoir to me until the end when we were done and I thought, “Oh, I see it now.” But as far as initial inspiration goes, I remember sitting up in bed in my rehab facility and picking up a pen and paper and asking myself, “Why am I here?” That’s when the first story got written.

TMS: Why do you think it’s so important to have Black coming-of-age stories?

Broome: In the book, I talk about some things that, frankly, I’m embarrassed about. The way that I viewed myself as a Black child is part of the plan of white supremacy. I viewed myself as less than. I can’t point to a specific place or time when I received that message, but I received it loud and clear. And I learned to hate myself. I tell these embarrassing stories because I don’t want any Black child in America to grow up thinking that they are less than.

Even in this age of so-called “diversity,” the message that Black people’s lives are worth less than white ones gets out there. It’s still pretty pervasive. And the message doesn’t just poison white people’s minds; it can poison Black people’s minds, as well.

Black coming-of-age stories are important because, unfortunately, America doesn’t provide Black children with a very long childhood. They get seen as adults very early on in their development, and I think it’s important for everyone to know how wrong this is. Black children aren’t afforded the luxurious innocence of youthful folly. I think stories are a great way to let everyone know that Black children are children.

TMS: The Black experience is one that is nuanced and wonderfully multifaceted, but it’s often boxed into a monolith. How do you think you’ve challenged that now, as an adult, versus when you were growing up?

Broome: In the small, mostly white town where I grew up, I think I really did believe that I was responsible for representing Black people. So, I tried to be as agreeable as possible. I tried to stay out of trouble. I tried to be funny and gregarious. But it was all an act, and an exhausting one at that. At that time, I wanted to be seen as the “good Black boy” but for all the wrong reasons.

I also found myself judging other Black people based on this “we all represent each other” model. I remember sitting and watching the local news and thinking “please don’t let him be Black” when they would report on a crime. Because we have all come to think of each other as representatives of our “race.” This is also a function of white supremacy, in my opinion.

Now, I really just try not to judge other Black people for believing differently than me even when I’m disappointed by their beliefs. I try in my own small way to push back against this narrative that we all represent each other. I feel that one of the ways I’ve challenged the idea of a monolithic Black community is by writing this book.

TMS: Punch Me Up to the Gods beautifully explores not only the generational trauma, but the cultural trauma that breeds this sense of toxic masculinity in the Black community. What ways do you think these cycles can be confronted and healed?

Broome: This is a question for which I really have no answer. I wish I did. I think these conversations around toxic masculinity are just beginning, and challenging the ideas that fuel it isn’t going to be easy. Men use it to shame one another, and shame is a powerful tool when you want to make someone behave the way you want them to. The only thing I can think of is to find a way to confront the shame and make men recognize that overcoming the shame that was put into them is the real test of fortitude.

I see things changing, though. I see boys from all backgrounds being allowed to use their minds and bodies in the ways that they see fit. But the shame placed on boys for being “like a girl” isn’t going anywhere any time soon.

TMS: How do you find inspiration in your day to day?

Broome: I think about the person I used to be. I meditate on how I have used my pain as an excuse to cause pain to others. Addiction isn’t ever ennobling. I stole. I lied. I treated other human beings as a means to an end to make me feel better about myself.

It inspires me to get up every day and try to defy that version of myself. It sounds cliché, but I try to do something nice for at least one person every day. Even if it’s just to make them laugh. I find inspiration in the friends who have stuck with me. And I find inspiration in my writing students. But mostly, I just love sitting in the peace and quiet and taking some time to be grateful. Because I am blessed with a lot.

TMS: What advice would you give to young Black writers—or creatives in general—today? Are there any other stories—fiction or non-fiction— that you’re interested in exploring and telling in the future?

Broome: For young Black writers, I would just say to keep writing. It doesn’t have to be a story about your Blackness. Write your story about space aliens and vampires and magic. Write your superhero story. Write your epic, romantic period piece. Make up a language. Create whole different worlds. Just keep writing and showing it to people.

Right now, I have a few ideas about what I want to write next. It’s just a matter of focusing on one of them and setting myself to the task. I’m writing right now, but I’m not sure in what direction it’s going to take me yet.

TMS: Punch Me Up to the Gods has a beautiful introduction by Yona Harvey, as well as the wonderful poem “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks. What Black writers/creatives have inspired you on your writing journey?

Broome: I love Yona Harvey. Her work is so beautiful. Apart from her, I always remember loving Grace Jones. She seemed so free. I remember seeing her for the first time, and I thought she was the most beautiful person in the world.

I have been inspired by so many Black artists that I think it would become boring for me to list even half of them. I can tell you that, right now, Michaela Coel is an inspiration writing-wise. She has the ability to make you laugh and break your heart all at once. I think she’s a genius, personally.

I love bell hooks and how long it takes me to decipher what she’s saying because she’s so smart. I mention in the book how James Baldwin is an inspiration to me but not necessarily because of his writing. I think he was a great writer, but I find the way he lived his life in general to be more compelling.

Black people from all over the world have always created beautiful art in all its forms. Far too many to just hang my hat on one.

TMS: What does “Black Boy Joy” mean to you?

Broome: Freedom. Just being free of the constraints that the American ideas of Blackness and Manhood places on us. However that looks, I’m for it. I would think that this is a goal for all Black people—not just boys or just girls or just men or just women. In 2021, Black people are still trying to get free.

(image: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: May 18, 2021 04:02 pm