If the summer’s glut of sequels and reboots has got you down, then interest, if not a feel-good time, may be found in the art house. Byzantium, a return to the vampire genre well-trod by director Neil Jordan in High Spirits and his more famous Interview with a Vampire, is a curious piece, at times slow and ponderous, bookended by violent, swift action. It brings Jordan back to a theme he explored in Vampire; the consequences, and perpetual loneliness, of the cursed immortal.

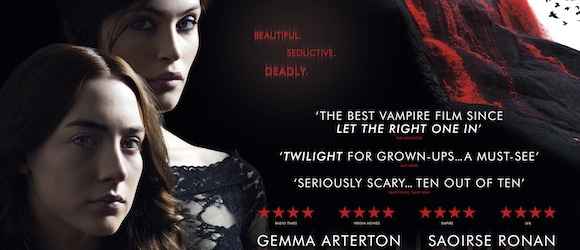

The difference here is that the subjects of Jordan’s very modern supernatural tale are not statuesque vampires in sharp suits and gleaming jewels, but a mother-daughter pair, sleeping rough and on the run. Having defied a patriarchal Brotherhood whose rules state that women cannot create succients (the film’s preferred term for its vampiric denizens), Clara Webb (Gemma Arterton) and her daughter Eleanor (Saoirse Ronan) are forever one step ahead of their pursuers, though Eleanor appears largely in the dark about their impending danger, or, at least, the reason for their being on the move. This reason, the reason for Eleanor’s creation, and the sorry tale of her mother’s history, is relayed in pieces throughout the film, as a frustrated Eleanor whispers to the wind and the sea, and finally, a young companion, the story she must never tell.

Mild spoilers, and discussion of trope-typical violence awaits readers under this non-sanguine cut.

Having brutally executed one of the men after her and her daughter at the film’s start, Clara grabs Eleanor and makes for a sleepy coastal town, hoping for a temporary respite and a fresh start. However, the two are unknowingly repeating themselves, returning to their beginnings, and, eventually, to the consequences of the choices they’ve made.

These are not the traditional vampires of many an Anne Rice novel and rip-off, for they can travel in the daylight, and have no fangs to speak of, using an elongated thumbnail as a puncture from which they can drink their victim’s blood. Each woman has her particular strain of ethics for killing, developed over time. Eleanor is a descending angel, killing only those sick or dying and ready to have their pain eased. Clara shows promise as a heroine at the film’s start; ruthlessly protective, fast on her feet, and not a little manipulative. But as the blood-drinking pair settle in at a dilapidated seaside resort, Clara loses much of her substance. She’s a piece of the story, and an important one, but she becomes a troublesome backdrop to Eleanor’s thoughtful present. Where the film initially promises much in the way of developing the relationship and interplay between mother and daughter, it slacks fairly quickly, focusing almost entirely on Eleanor. It feels like a betrayal, one about as fierce as seeing Clara reduced by the narrative to a woman who, having been, it’s eventually revealed, traumatized into the profession, is fixated on being a prostitute. For the middle meat of this bloody tale, Clara stomps around on platform stilettos, barking orders and turning the once-fine hotel into a brothel to earn quick cash. She is both predator and prey, a dynamic that could have had real legs, if only it had been played out.

Eleanor could not be more different, yet the two have spent more time together than apart. It’s a curious conundrum, one never addressed by the film, that both have remained so set in their ways for so long. Eleanor is quiet, given to brooding, with a penchant for penmanship, and practicing piano sonatas (she seems fond, not inconsequentially, of Beethoven). The striking separate natures of the mother and daughter are enough to make an audience ask, what’s 16 formative years versus 200? A lot, apparently, as Eleanor sticks to her behaviors just as vehemently as her mother sticks to hers.

But Eleanor’s long silence may have finally found its end in Frank (Caleb Landry Jones) an imaginative, fragile leukemia survivor of Eleanor’s apparent age. Jones, an actor whose ethereal facial qualities are a twin to Ronan’s, begins a tentative flirtation with this seemingly old-fashioned, odd girl. There is, thankfully, none of the imprint of the now-archetypal paranormal teen romance to mar their delicate, awkward courtship, with Frank’s earnest nature convincing Eleanor that here, finally, is someone to whom she can tell the truth. Unfortunately, the truth sounds like nothing of the kind, and belief in Eleanor’s tale, as Frank comes to know, proves far more dangerous than writing it off as imaginative fantasy.

Jordan has a flair for visuals, shooting his period scenes and contemporary sets with the same half-lit, lurid quality. There is no dreamlike world of the past, nor is there an unclouded, solid vision of the present. Everything is shrouded in twilight or overcast days, allowing every puddle and droplet of blood to glisten in stark contrast to their surroundings. Whether in neon, candlelight, or broad day, danger seems to loom, ominous, but for whom it is uncertain. Symbols repeat, but seem disconnected, objects seem to have importance, but remain unfocused upon. It’s almost as though there is a far more complex structure just beneath the surface of things, that, when looked at too closely, proves nothing but an illusion of good shooting.

Still, Byzantium has a host of original constructs in its holdings, the best of which is the details of the transformation from mortal to immortal succient, the likes of which has never been portrayed quite this way before. Though deeply flawed and, at times, formless in structure, Byzantium never bores, keeping its audience waiting for that final conclusion, whatever it might be, even if it disappoints. In the grander scheme of these things, it’s better to see a film take big, splashing risks and sometimes falter for them, than suffer through another typical blockbuster that dared do nothing different.

Byzantium is currently in limited release in New York City and Los Angeles, so if you’re not near either of those, you might want to wait for a home viewing release.

Published: Jul 1, 2013 10:58 am