Marvel’s New Editor-in-Chief Admits to Writing Comics for Them Using a Yellowface Pseudonym

Marvel’s new editor-in-chief, C.B. Cebulski, has admitted to writing a number of titles for the company under the “Japanese” pen name of Akira Yoshida in the early 2000s. Cebulski, posing as Yoshida, wrote issues of Elektra: The Hand, Wolverine: Soultaker, Thor: Son of Asgard, X-Men: Age of Apocalypse, and more.

In communication with Bleeding Cool (I know, I know), Cebulski reportedly confirmed his use of the pseudonym after years of Marvel higher-ups insisting that Yoshida was real. “I stopped writing under the pseudonym Akira Yoshida after about a year,” he wrote to Rich Johnston. “It wasn’t transparent, but it taught me a lot about writing, communication and pressure. I was young and naïve and had a lot to learn back then. But this is all old news that has been dealt with, and now as Marvel’s new Editor-in-Chief, I’m turning a new page and am excited to start sharing all my Marvel experiences with up and coming talent around the globe.”

While I appreciate that Cebulski has owned up to this behavior, his statement doesn’t seem to reflect a real understanding of the harm he caused. By lamenting only the fact he “wasn’t transparent,” and chalking it up to being “young and naïve,” Cebulski ignores the ways that white co-opting of marginalized identities costs minority writers and artists jobs – and the way that it contributes to harmful stereotypes.

Because Marvel didn’t just hire Cebulski’s “Yoshida” to write cape comics (though that would still be terrible). They hired him to write a number of books that were, as David Brothers so aptly described them, “Japanese-y.” In both his arc for Wolverine: Soultaker and his work on X-Men: Kitty Pryde — Shadows & Flame, the main adversaries were … ninjas.

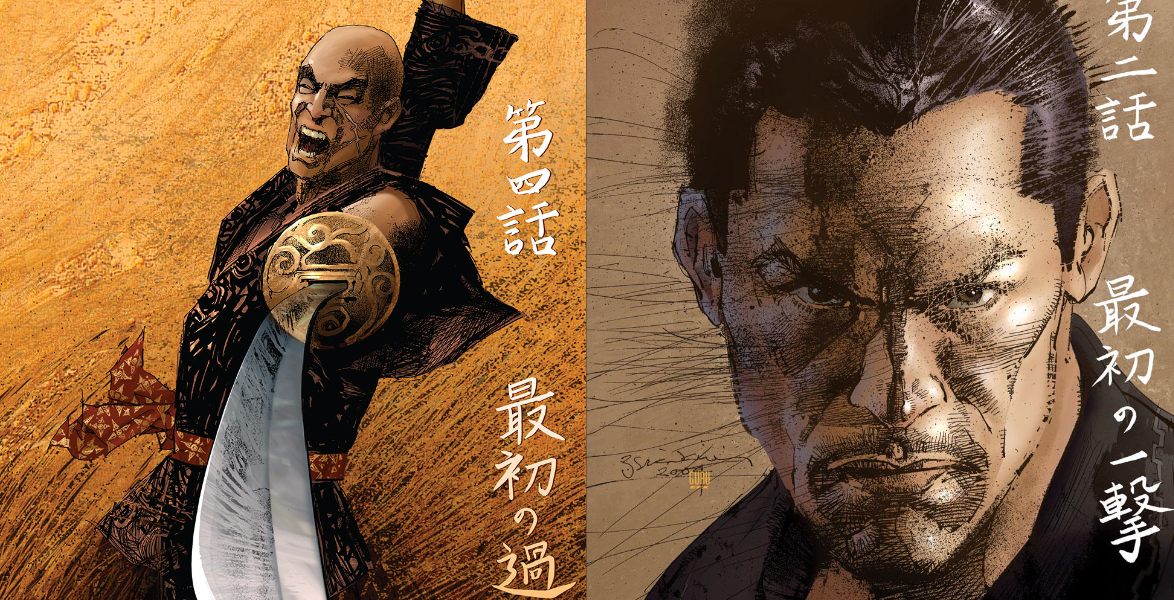

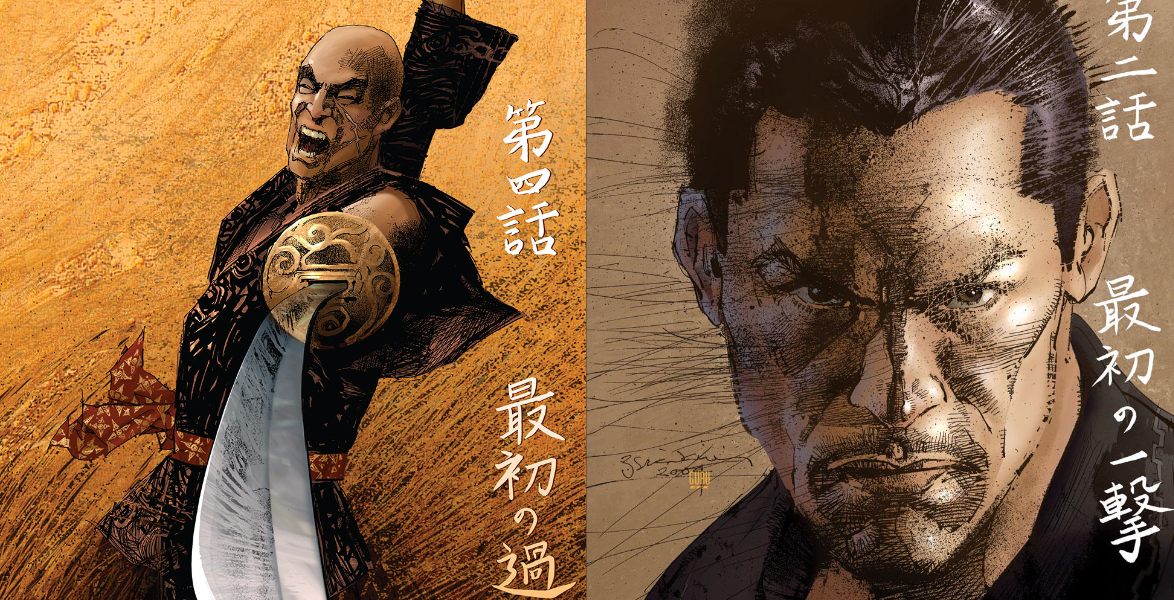

I mean, these are some of the covers for issues of Elektra: The Hand that “Yoshida” wrote.

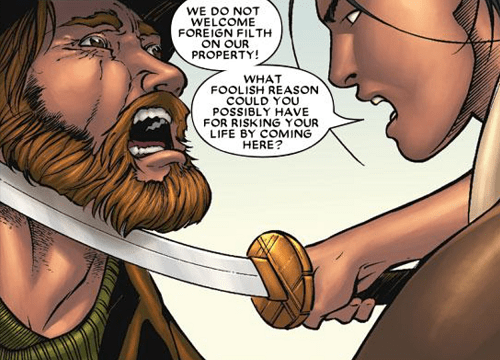

Elektra: The Hand traces the formation of the Hand as a group of Japanese samurai who specifically want to keep foreigners (read: Westerners) out of their land. It centers on one of The Hand’s trainees, a half-Spanish, half-Japanese girl named Eliza who faces prejudice because of her heritage. And while it’s certainly true that Japan has a history of racist reactions to mixed-race people – just look at the comments about Ariana Miyamoto, the half-black, half-Japanese woman who represented Japan in the 2015 Miss Universe pageant – that isn’t the sort of issue that Cebulski is best-suited to address. And it’s certainly not an issue which should be addressed by a white man writing about historical Japan, when the country’s anti-foreigner sentiments were messily tied up with a necessary resistance to Western colonialism. Like, these panels are not nuanced.

Cebulski also created an entire backstory for his Yoshida pseudonym. A 2005 interview with CBR introduced Yoshida as a writer who “grew up in Japan reading manga. Since his father was in international business, he spent parts of his childhood living in the U.S. where he learned English by reading superhero comics and watching TV and movies. As a child, the writer said he always wanted to work in either the Japanese manga or American comics industry. Fortunately, he’s had the privilege of doing both as an adult.”

The article then goes on to describe how Yoshida got his start at a Japanese comics publisher called Fujimi Shobo, and then attended a few U.S. conventions, where he made contacts with some American editors and thereby got his start.

Cebulski’s use of a pseudonym here clearly echoes poet Michael Derrick Hudson’s infamous “yellowface” entry in Best American Poetry 2015. Hudson submitted his poem under the pseudonym, Yi-Fen Chou, writing that “after a poem of mine has been rejected a multitude of times under my real name, I put Yi-Fen’s name on it and send it out again. As a strategy for ‘placing’ poems this has been quite successful for me.”

Now, unlike Hudson, Cebulski hasn’t tried to justify himself with a repulsive suggestion that minority writers are only published because of some sort of affirmative action based around their ethnic identities. (You’re still the grossest, Hudson!) But his use of the “Yoshida” name to write multiple, specifically Japanese-centric stories suggests that he was doing more than circumventing company policy. (Marvel didn’t allow its employees to both edit and freelance write for them at the same time.) It suggests that he was adopting this pen name in order to mime authenticity so that he could write stereotypical stories about ninjas and honor without receiving any flack.

Whatever Cebulski’s underlying motivations, the fact that Marvel learned about this and still hired him as their Editor-in-Chief is, as so often for the Big Two, not a good look. It also raises questions about who else at Marvel knew Yoshida’s real identity. Cebulski refers to this as “all old news that has been dealt with,” but for most people, this is new information. So for whom at Marvel is it “old news,” and for how long have they known? And how it was decided that everyone would keep Yoshida’s real name a secret?

(Via Bleeding Cool and The Hollywood Reporter; image via Marvel Comics)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]