The Artist is receiving many an accolade for its ambitious take on that peculiar episode of American cinema, the passing of the silent film to make way for “talkies”. It’s a beautiful effort and a challenging watch, and it addresses that most artistic question of all artistic questions, that being: What is it to be an artist when it becomes impossible to practice that art?

To the silent film actors at the end of the ‘20s, that question was a near constant concern, with varying opinions addressing philosophical and practical worries. The Artist barely addresses any of the milestone events during this transformation, choosing instead to focus on the acutely personal angle. The struggles that George Valentin faces in The Artist were echoed by many of our most popular film stars of the era.

The film glosses over the reality that sound film began to be introduced as early as 1923, with screenings of a new patented sound-on-film technology retroactively fitted to silent films that was immediately popular. The major studios all scrambled to procure and adapt the technology for making big studio films with sound incorporated. The transition was inevitable, and stars had a good lead-in to appreciate what was coming.

However, it’s true that the come-to-Jesus moment was the 1927 release of Warner Brothers’ The Jazz Singer, in what one critic derisively called “an enlarged Vitaphone record of Al Jolson in half a dozen songs.” Despite the possibly fair judgment that the film was created entirely to show off the technology of sound film, the film was a massive hit and turned the lights on in moviegoers’ heads – sound was more realistic, it allowed for more range, and it was more interesting. There wasn’t a question of its superiority – for most.

Some still felt that sound film was gauche, the epitome of tackiness. Thomas Edison was annoyed by the early stiffness of sound film, an eventuality created by the limited range of motion afforded to actors who needed to stay within the microphone’s arena. One of the first ever beta products, sound film suffered from several technological drawbacks: in addition to the limited movement, cameras at the time were extremely noisy and were interfering with shooting, there were difficulties syncing the actors’ mouths to the dialogue, and the demand for screenwriters (a phrase one does not expect to ever read) to write more than just inter-titles was high. Edison grew frustrated with the enterprise and returned to making silent films with era stars like Clara Bow.

Bow, too, suffered a little from an issue that plagued many silent stars in attempted transitions to sound: a strong accent. She and her Brooklyn twang made it into talkies with little issue, but heavily accented foreign stars like the German Emil Jannings or Hungarian actress Vilma Banky found their speech to be a bigger hurdle. George Valentin’s French accent in his single line at the end of The Artist pays tribute to this idea. Another issue preventing many stars’ transition into the talkies was their lack of voice training – it hadn’t been necessary in their prior careers, and many lacked compelling voices to audiences. The little-known Norma Talmudge suffered from this effect and resigned from films after her first talkies weren’t successful. When asked for an autograph after her cinematic departure, she told the fans, “Get away, dears. I don’t need you anymore and you don’t need me.”

Most actors capitulated and made the transition as best they could, and it’s fair of The Arist to suggest that certain of them, like its fictional heroine, the Ruby-Keeler-modeled Peppy Miller, did quite well for themselves. Lillian Gish, D.W. Griffith’s silent film darling, took a decade off to do theater and returned to film, garnering acclaim and a few Oscar nominations along the way. Joan Crawford, the eminent head bitch in charge, made a very successful career in sound film until old, old age. Clara Bow, while decrying the loss of “cuteness” in talkies, which she hated, also admitted that she couldn’t “buck progress” and adapted as well as she could. Which is to say, not very, developing a steady addiction to sedatives and liquor that lasted her the rest of her life. To be fair, that may not have been the doing of sound film so much as the result of waking up to her mother holding a knife to her throat when she was a child. Eek! But that’s a horror story for another day.

The Artist over-dramatizes the swiftness of the transition into sound film, however. As mentioned above, Edison continued to make silent films that did fairly well. Europe and Asia transitioned slightly later and much later, respectively – as late as 1938, a third of Japan’s films were still silents. Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel produced the seminal Un Chien Andalou in 1929 as a purposely silent film. And the Great Resistor of them all, Charlie Chaplin, made Modern Times in 1936 (!), the last American silent film that was extremely successful in its own right, and both commercially and critically popular in its time.

The film began as a talkie, ironically enough, since Chaplin hated sound film, and the subject matter obliquely deals with as much. Chaplin stars as a factory worker trying to survive the iniquities of modern invention, finding himself lost among the mass production and meaningless of the individual. The film is a comedy, to be sure, but in that special way Chaplin has of bringing humor to its depressing conclusion. In 1929, Chaplin stated that “Talkies are ruining the great beauty of silence. They are defeating the meaning of the screen.” Even Chaplin couldn’t hold out forever – in 1940, he produced his first sound film, The Great Dictator, one of the first anti-Hitler works of art.

Sound was always intended to be part of film, and its absence for the first three decades of its history an aberration due to the restrictions of a technology that tripped over itself in its youthful exuberance. That’s not to say this transition didn’t have some real and occasionally devastating effects on human beings’ lives, and The Artist is a beautiful, if simplistic, treatment of that time period.

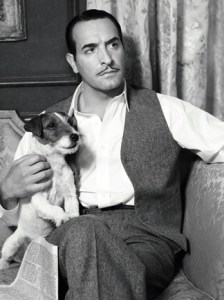

Although it’s worth it to point out that the human being our protagonist George Valentin seems to be based on did fairly well in the endtimes of silent film.

William Powell, he of the handle-bar mustache and little terrier dog above, had a deep and charming voice that suited him well in talkies. He and actress Myrna Loy were a superstar combination, and he hit it extremely big with her in The Thin Man, becoming A-list overnight. So, you see – progress wasn’t so bad for everyone. Especially, in this particular case, Jerry Bruckheimer.

Natasha Simons was a film studies minor who wishes she were as baller as Joan Crawford. She blogs here.

Published: Dec 15, 2011 12:34 pm