During this year’s E3, a new trailer for BioWare’s upcoming game Mass Effect: Andromeda was released, calling upon players “to build a new home for humanity” in the Andromeda galaxy. Much like last year’s N7 Day video, the trailer beautifully called back to humanity’s own history of spaceflight, reflecting on our “drive to seek out the undiscovered, [and] push beyond our limits.” But amidst the orchestrated music and stirring visuals is the realization that this game is the story of a colonial expedition, a search for new land where humanity may live.

This is the unfortunate truth of how space exploration is conceptualized, both in real life and in our fiction. Our incentives for travelling to the stars are to strip asteroids of their minerals, to establish bases and colonies, and for humanity’s presence to reach out into the universe. There is something genuinely inspirational about those goals, something I’m sure many scientists and fans of science fiction (including myself) have experienced firsthand. There’s nothing quite like looking up at a night sky and thinking to oneself, “I could go there one day. I could touch those stars.” We have a want to find answers to what we do not understand, to travel to places beyond our reach. Those impulses have led humanity to do many great things, but also have fueled some of the greatest acts of violence people have committed.

The rhetoric that taps into those impulses, of “reach[ing] for new heights and reveal[ing] the unknown” is used both by fiction like Mass Effect and real space agencies, such as NASA. But it’s also the same rhetoric used to describe colonial figures such as Christopher Columbus, as a way to erase their violent histories. Despite clear historical proof Columbus’ expedition was aimed at the acquisition of gold and slaves, he is still characterized as a brave explorer, who went into the unknown for the betterment of humanity. He is put alongside people like Neil Armstrong or the Wright brothers, as a part of a (Western) legacy of human exploration that must continue.

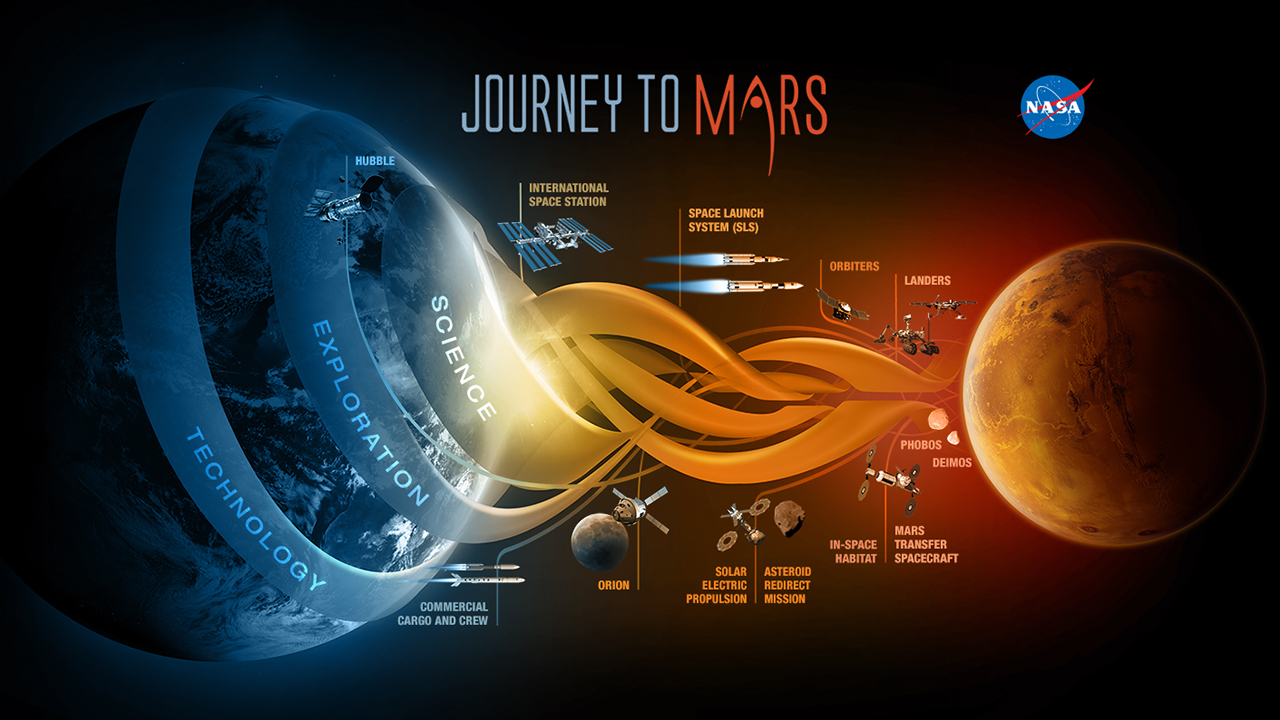

That this rhetoric has been used to justify unfathomable violence should be of great concern to those of us that view the exploration of outer space as a virtuous endeavor. Up until now, this hasn’t been a concern because of both the technological limitations of our travel and the absence of any life with which conflict may arise. Armstrong’s arrival on the Moon – though highly political within the context of the Cold War – cannot be compared to Columbus’ blood-soaked “exploration” of the Americas. But with NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) preparing for its first launch in 2018 and pointed towards Mars – the most likely place to find life within our Solar System – space exploration as an extension of colonial violence could become a reality within our lifetimes. There are already groups looking into commercial asteroid mining for the near future, and as humans begin to visit Mars and the Moon more permanently, questions of ownership over those spaces will arise as well.

The notion that space exploration and colonialism are connected isn’t something new, and has been addressed by science fiction for some time, though usually without a positive outlook towards humanity’s future. Films like James Cameroon’s Avatar or Ridley Scott’s Alien depict a future where humanity uses outer space to mine for resources. And though Avatar shows a group of individuals turning against that mining operation and joining with the indigenous population, there is no envisioned future where humanity ceases such operations completely. Star Wars depicts a future (well, technically a past) where trade corporations and dictatorships flourish while democracy flounders. But how do we envision a future where there is no Empire to begin with? Star Trek comes closest to achieving this, imagining a future without currency, where various species coexist within a Federation, and the Prime Directive preaches non-interference above all. But even the Federation grapples with the deeply colonial overtones of its existence, something often explored through the show but not given the nuance it deserves in comparison to more straightforward conflicts, especially on the big screen. If the most common depictions of the end-result of humanity’s space exploration are filled with mining operations and fascist or quasi-neoliberal governing bodies, how can we expect the future of our reality to be any different?

The notion that space exploration and colonialism are connected isn’t something new, and has been addressed by science fiction for some time, though usually without a positive outlook towards humanity’s future. Films like James Cameroon’s Avatar or Ridley Scott’s Alien depict a future where humanity uses outer space to mine for resources. And though Avatar shows a group of individuals turning against that mining operation and joining with the indigenous population, there is no envisioned future where humanity ceases such operations completely. Star Wars depicts a future (well, technically a past) where trade corporations and dictatorships flourish while democracy flounders. But how do we envision a future where there is no Empire to begin with? Star Trek comes closest to achieving this, imagining a future without currency, where various species coexist within a Federation, and the Prime Directive preaches non-interference above all. But even the Federation grapples with the deeply colonial overtones of its existence, something often explored through the show but not given the nuance it deserves in comparison to more straightforward conflicts, especially on the big screen. If the most common depictions of the end-result of humanity’s space exploration are filled with mining operations and fascist or quasi-neoliberal governing bodies, how can we expect the future of our reality to be any different?

Science fiction has always had a profound impact on human spaceflight, with shows like Star Trek inspiring generations of astronomers and engineers to work towards a spacefaring future. Perhaps in the same way the communicator allowed us to dream up the cell phone, or the Nostromo’s mining expedition imagined asteroid mining as a reality, Mass Effect or similar works of fiction can help us explore our methods of exploration, challenge us to consider the damage an interstellar colonial project could cause, and force us to dream of a better way. A future where we explore space not as conquerors or colonizers, but observers to the universe, seeking to understand and not impose. Where instead of finding more ways to harvest material resources, we discover more forms of renewable energy. Where our interactions with new life are not based on the imposition of power, but respect and consensual collaboration.

These notions may sound fanciful, but that’s the point of science fiction: to dream stories of the impossible, planting ideas that may one day become realities. Whether this anti-colonial approach is where Mass Effect: Andromeda’s story will go, we will only find out early next year upon release. Regardless, we need stories that lead us towards a decolonized vision of space exploration, with nuanced representations of the diversity we have on Earth, and bold imaginings of what humanity’s part is in whatever lies beyond. If the next generation of scientists and explorers grow up with stories like that sparking their minds and imaginations, humanity has a chance of breaking away from our violent past (and present), to discover a better future among the stars.

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Published: Jul 17, 2016 11:00 am