“Games” is a fairly science-light episode of seaQuest DSV. The crew is tasked with recovering a single, extremely dangerous convict from a prison built of ice in the far arctic. Unsurprisingly, the evil genius Dr. Zeller, who was supposed to be cryogenically frozen for transport, has swapped places with the warden and is now free to run amuck onboard seaQuest. After half an hour of cat-and-mouse, Zeller traps Bridger in the missile control room and forces him to attack Pearl Harbor. But, of course, Bridger saw this move, the missiles were duds, and Zeller is captured. Hooray.

It is perhaps not a great idea to build a prison out of material that melts, especially as the world warms. What’s truly exceptional about this episode is how casually global warming is taken as given. It’s a strong reminder that climate change was not always politically polarizing and that, at some point in the 1990s, it was a bipartisan, populous issue. After all, Cap and Trade was a quintessentially Reagan-esque idea. In a lot of ways, we’ve regressed from the political reality of 1993. I can’t think of any modern show that would so casually incorporate climate change into the plot without wrapping it in a ham-fisted political message.

Since the science and conservation is so light in this episode, I might as well take the opportunity to talk about two larger issues in the series.

First off, can I just say I really enjoy finding random pieces of marine equipment used as random props? In Battlestar Galactica, there was a Perko switch—a big red and black circular device used to swap or disconnect boat batteries on an outboard motorboat. I had the exact same switch on my research skiff, Iffy, and I used to play “spot the switch” for every episode. It showed up a lot. In seaQuest, it’s regulator mouthpieces, pressure hoses, and other bits of diving paraphernalia that keeps popping up in random places. Our cryogenically stored warden has a spare SCUBA mouthpiece, but nothing else, lodged in his mouth. Neat.

Second, I feel like having the technology to talk to dolphins would be a bit of a big deal. Being able to carry on meaningful conversations with an entirely different species seems like it should be much more significant, not something relegated to the care of a teenager who wears ironic, fish-themed baseball jerseys.

In all seriousness, while there’s a small number of scientists seriously asking whether humans can talk to dolphins, there’s quite a few research programs exploring how dolphins and other marine mammals communicate with each other, and how the audio seascape shapes how marine animals interact with their environment.

Bob Ballard arrives to close out the episode and finally answers the question that should have been covered in the very first end-credit footnote: What does DSV ever mean? Deep Submergence Vehicle, which for the record, is a real classification for deep-diving assets, though conventionally, the DSV comes before the name, as in DSV Alvin, DSV Sea Cliff, DSV Trieste II, and the rest of a slowly dwindling fleet of deep-diving submersibles.

“Treasures of the Tonga Trench” is a paint-by-numbers Dragon’s Horde episode. On a routine dive in the Tonga Trench (a real trench that occurs just east of the Lau Basin in the southwest Pacific), Lieutenant Krieg faces off against a mysterious tentacle monster before discovering a cache of glowing rocks. He brings the stone back to seaQuest and immediately begins to scheme about selling them on the international market. He can’t keep his secret for long, and soon almost the entire crew is in on the action.

Meanwhile, there’s a weird subplot involving a military inspector who is unimpressed with the state of seaQuest and, for reasons unknown, decides that the best way to test the sub if to see how many pushups the captain can do. At one point, they actually compare the firmness of their butts. That’s not really how any of this works, and it’s all weirdly out of character for Bridger.

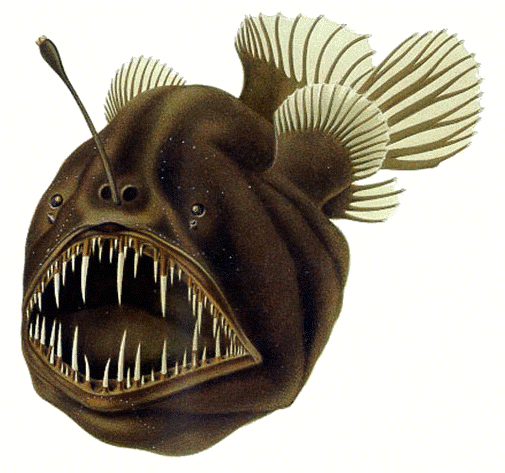

We get our first seaQuest glimpse of the angler fish. I love angler fish. They’re weird and glowy and fearsome and, well, tiny. Seriously, most anglerfish are only a few centimeters across. But, of course, everyone’s favorite fact about the anglerfish, made immortal by the Oatmeal, is that anglerfish have parasitic dwarf males that permanently attach to the female, fuse circulatory systems, and are eventually reduced to a pair of genetically distinct gonads hanging off the female.

“Wait, Andrew, you’re not about to ruin anglerfish for us, are you?”

Sort of. Sorry.

This is Melanocetus johnsonii:

When most people picture anglerfish, they picture this species. It’s the species the Oatmeal comic is modeled on. Here’s the funny thing: While almost all anglerfish species have parasitic dwarf males, Melanocetus johnsonii don’t. The entire Melanocetus genus has dwarf, but free-swimming, males. But don’t worry, there’s plenty of other novel reproductive strategies in the ocean. Heck, the female bone-eating snot-flower worm (seriously, that’s the literal translation of Osedax mucofloris) has dwarf male harems that live inside a special organ just for them, to the tune of several hundred males per harem.

Back to the gems: While most people think of the high seas as functionally lawless, there actually are strong international regulations that govern the collection of seafloor resources in international waters. The International Seabed Authority is a United Nations agency tasked with safeguarding high seas resources “for the good of humankind” (an aside: employees at the ISA refer to it simply as “The Authority,” which has led to some fantastically ominous international meetings where an ISA representative, calling in via Skype, projected on a theatre screen, and poorly backlit, so as to look like nothing so much as a shrouded, faceless, gigantic head, announced that “The Authority will act for the good of mankind”). What “the good of humankind” means is that, technically, we all own high seas mineral resources; they’re part of our “common heritage.” You can’t just go into international waters and say “this ore is mine.” There is a process of leasing and distribution, and some component of the profits from the extraction is allocated to developing nations.

This is part of the reason why the first deep-sea hydrothermal vent mines are happening in national waters, rather than the high seas. Basically, the seaQuest crew is stealing from me and stealing from you, and for that matter, the crew of the world’s preeminent scientific and military submersible should probably know that. They’re violating any number of international treaties, which would cost them their commission.

Or, at least, it would if it didn’t turn out that the glowing rocks were actually squid poop. Biological organisms and material don’t have the same overarching regulations as rocks do. If you have a big enough boat and have the right flag of convenience, you can take every Bluefin tuna you want out of the high seas—just don’t grab any rocks while you’re at it. While we’re on the subject, the United States still hasn’t ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, so the only high seas laws that apply to the United States are the ones for which we have congruent national laws. International ocean governance is weird.

Andrew Thaler is a deep-sea ecologist and conservation biologist who runs the marine science and conservation blog Southern Fried Science. You can support his various and sundry ocean outreach projects (like this one) on Patreon or check out his maritime-y science fictions novels. Follow him on Twitter, where he’s happy to answer question about deep sea ecology and exploration.

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Published: Apr 23, 2016 11:00 am