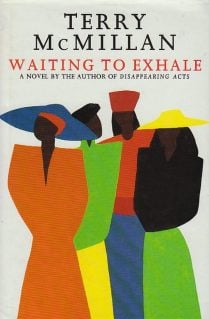

Despite Its Legacy, We Deserve a Better Version of ‘Waiting To Exhale’

Recently, for the first time ever (seriously), I read Terry McMillan’s Waiting To Exhale and watched the film adaptation directed by Forest Whitaker. The story follows four Black girlfriends in their thirties: Bernadine (Angela Bassett), Savannah (Whitney Houston), Gloria (Loretta Devine), and Robin (Lela Rochon). While the book delves more into the financial and familial aspects of their lives, the 1995 film zooms in on the love and loss the women experience.

Based on how I see people talking about it (particularly Black women and femmes online), I feel like I’ve checked off a film on a community-curated list of must-watch movies. I’ve watched documentaries and video essays about film history, and Waiting To Exhale is never brought up despite its cultural impact. Lately, the film has had a resurgence in popular culture, from the “a good man Savannah” line making the rounds on TikTok, to renewed attention on Whitney Houston’s legacy via the new biopic, I Wanna Dance With Somebody, starring Naomi Ackie. In addition, costume designer Judy L. Ruskin’s keyhole-cut dress (worn by Robin in the film) has gained renewed interest (and tutorials) in tandem with the cut-out trend of 2022.

This month marked the 27th anniversary of the movie’s release and 30 years since the debut of Terry McMillan’s best-selling novel—a novel that made Zora Canon’s list of the 100 greatest books written by African American women, and was placed firmly in the era highlighting “the strength of self-worth.” In honor of the anniversary and the New Years’ Eve reflections present in both the book and the movie, I wanted to talk about what worked and didn’t work in the film, and how McMillan’s story can be adapted again to better embody the richness of the novel and reflect the experiences of Black women in the ’90s, now that some time has passed.

Waiting To Exhale (1995)

Let’s rip the bandaid off. While I enjoyed the film overall and liked the book even more, Waiting To Exhale was not a great film, even for its time. It’s a poor adaptation, and certain elements have aged more poorly than others. From a technical standpoint, the editing missed several blunders (including visible blocking tape) and resulted in less-than-smooth transitions between scenes. That alone doesn’t mean it’s a bad movie, of course—you can find mistakes in multi-million dollar franchises, and this was actor Forest Whitaker’s directorial debut, on a feature film that received a wide release, no less.

In addition to the technical aspects, the story is clunky and cuts the meat from the narratives of half of the main cast—Robin and Savannah—to such a degree that I could have the characters combined into one fully formed woman with more screen time than the two-dimensional characters who made it to the screen. That’s a shame because while Robin was the worst character throughout most of the novel, she grows on you by the end. I can’t say the same for the movie. Gloria and Bernadette’s characters remain mostly intact, but they were also the strongest in the novel (and closer in age to the author). Also, because they have the most stability in their lives (and are much more mature), there’s not as much reliance on internal monologue as there is with Savannah and Robin—which is hard to capture well in a film with four main characters.

Before reading the oral history of Waiting To Exhale‘s production, I was under the impression that this was one of those rare Black adaptations optioned and filmed at the time of the book’s release, so the script was based more on author’s notes and an early manuscript. In journalist Aramide Tinubu’s interviews with the cast and crew, however, she learned that the buzz came after the book’s release, and that this was a film everyone wanted to be a part of. But something was lost in Ronald Bass (who went on to adapt another McMillan book) and McMillan’s adaption of her novel. Most of the highs and many of the lows were effectively transferred to the screen, but the nuance was lost in translation.

What I did love about Waiting To Exhale was the casting (half of Black Hollywood is in this movie!), the performances, and the soundtrack. This isn’t exactly a hot take, but that soundtrack is beloved and is just as much a love letter to Black women as the movie aimed to be. In addition to Whitney Houston (because of course), Toni Braxton, Aretha Franklin, Brandy, TLC, Mary J. Blige, Chaka Khan, Patti LaBelle, Faith Evans, CeCe Winans, and more lent their voices to the soundtrack. While Babyface was the lead producer and wrote many of the tracks, it was the first soundtrack to feature all women performers. The soundtrack perfectly captured the beginning of the contemporary R&B that sprang out of the late ’80s.

Despite the many technical and storytelling flaws in the 1995 film, I love that it exists. For one, it was one of the last few Black films during a time when that term was more narrowly defined. The ’80s and the ’90s marked the decline of Black cinema in Hollywood—and I’m not even talking in terms of quality, but in quantity. While it was great to see Black actors (mostly men) cast in roles that weren’t explicitly Black in the ’00s and ’10s, it became harder and harder to find mostly Black films unless you had the BET channel or could stand more than one Tyler Perry production.

The story acts as both a time capsule and a snapshot of the late ’80s and early ’90s, with timeless themes of self-worth, love, and friendship. We all have these four women in our lives, and more of us want to admit that we deal with these same relationship struggles. While societal pressure has eased up a bit overall thanks to the adoption of a bastardized form of feminism, the racism, internalized anti-Blackness, fatphobia, and homophobia (all of which are more explored in the novel) have shifted even less. Also, there’s still social media and a wider world in which we’re trying to prove ourselves and find happiness.

What a Waiting To Exhale remake would look like

This might be blasphemous to proclaim, but I would love for this film to be remade in the 2020s. I’m not talking about the series that ABC was developing as of 2020, and is said to center on the characters’ children, but something that focuses on these four women in this moment of their lives. It could be a single film, or better yet, a four-part limited series event—this way each of the main characters has plenty of space to have their story told adequately. Think Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life, but good and without the leap in time. Waiting To Exhale‘s story fits the mold pretty neatly, and would allow the story to be sectioned into four seasons because the events begin on one New Year’s Eve and end on the next.

And most of the original cast could come back as supporting characters in a remake. Whitaker is best known for his acting, and could play Robin’s father as he’s suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. Except for Savannah’s mother (whose voice has become memeified), all of the main characters’ parents (save for Gloria, who was always on her own) are missing from the film adaptation. Other than the important plot elements those characters could’ve enriched, it’s frustrating because Savannah’s mom encourages her to make bad decisions in the name of living the trad-life and because she needs money from her.

I’m not saying that’s unrealistic or not important to the story, but there was no balance between Savannah’s mother and the other parents because they didn’t make it to the film. In McMillan’s novel, Bernadette’s mother represents the high life of retirement and old attitudes, and functions as a support system to aid in child-rearing while Bernadette struggles through a nasty divorce. Robin’s parents are also old-fashioned, and struggling with making a decision to get more help as her father’s disability worsens. They also hate Russell, like everyone else. Russell needs more scenes, too, juxtaposing him against the men Robin is having casual sex with—both to show how terrible this man is (and not just because of the drugs) and to show how Robin, like many women, struggles to cut him loose.

One smaller element of the story that wasn’t quite fully realized in the book, but that could help anchor another adaptation, is the role of the women’s club in town. In the book, it was mostly used as a thing for the women to occasionally do and gave them an excuse to check in with each other when there wasn’t an impending disaster. It made sense to cut it from the movie, but if each character got more time and was more three-dimensional like they were in the book, it could be more fleshed out. All of the characters live in a white area, and the club is a source of community-building and networking. There is a class element there that’s waiting to be explored.

There’s no fully recapturing the iconic scenes of Angela Bassett’s Bernadine lighting that car on fire or Savannah knocking her drink onto the man’s lap (they both sound like Avatar: The Last Airbender characters), but with so many needless remakes being made, there’s no reason this one shouldn’t be considered—especially because it could add value to the story. This story deserves the opportunity not only to live up to the book, but to be reflected on more than 30 years later.

(featured image: 20th Century Studios)

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]