The Key Differences Between Afrofuturism and Africanfuturism (With Examples!)

Take a byte out of this.

Later this year, the highly anticipated sequel to Black Panther (2018), Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, releases. This will likely mark another big surge in wider public excitement and shared fan art depicting elements of Afrofuturism and Africanfuturism. Despite their similar origins and many cultural ties, these two genres within science fiction and speculative fiction tell very different stories.

What is Afrofuturism?

First brought into discourse in at least 1993 by Mark Dery in Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose, Afrofuturism is a genre featuring science fiction themes that address cultural issues Black people face in the past and present. The genre uses conversations about race and technology to imagine what the future or an alternative present could be like for Black people. Some within the greater Black diaspora (globally) that live in a place where they’re second-class citizens or were influenced by the Atlantic Slave Trade use this to describe their work.

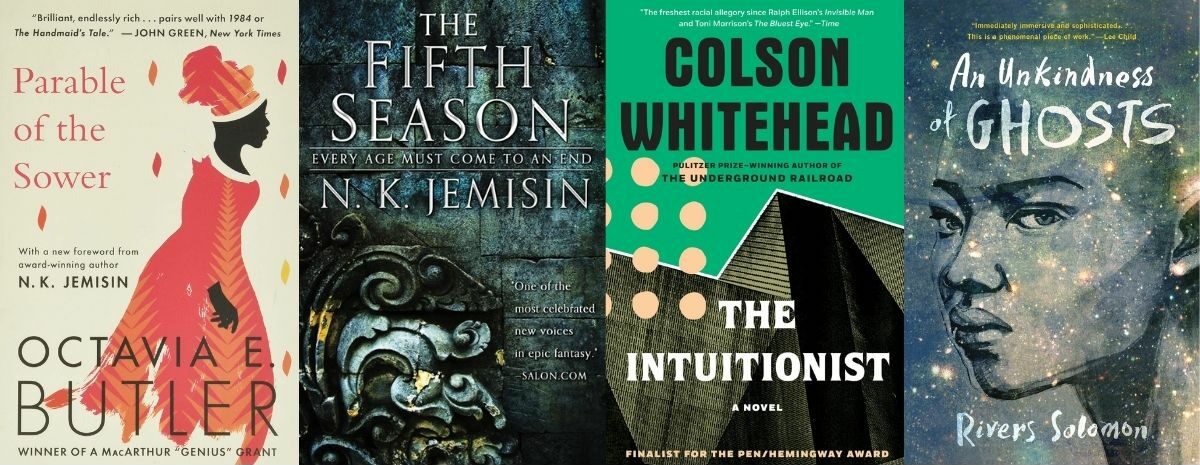

While coined in the ’90s regarding technoculture, many of its earliest examples include work created before as far back as the 1800s. Some 1950s-1990s work of writers Ralph Ellison and Octavia E. Butler, plus musicians like Sun Ra and Parliament-Funkadelic. Some recent literary examples include some works by N.K. Jemison, Rivers Solomon, Tomi Adeyemi, and Colson Whitehead.

Many contemporary visual and music artists have dabbled with Afrofuturistic aesthetics in their work. However, Outkast, Missy Elliot, and Janelle Monáe use these themes and aesthetics consistently. Monáe’s albums were my first meaningful interaction with Afrofuturism. Fellow TMS staff writer Princess Weekes did this *chef’s kiss* explanation of the genre for PBS two years back.

What is Africanfuturism?

Africanfuturism is similar, as it’s a type of science fiction, mainly in English or French, created by Black artists and writers. However, like Afrofuturism, this genre features its own nuances and arguably stretches back even further in time. While the phrasing has been in discourse since 2013, prolific Nigerian American writer Nnedi Okorafor coined the use as the literary definition in 2018 on her blog.

Africanfuturism is similar to “Afrofuturism” in the way that Blacks on the continent and in the Black Diaspora are all connected by blood, spirit, history and future. The difference is that Africanfuturism is specifically and more directly rooted in African culture, history, mythology and point-of-view as it then branches into the Black Diaspora, and it does not privilege or center the West.

Africanfuturism is concerned with visions of the future, is interested in technology, leaves the earth, skews optimistic, is centered on and predominantly written by people of African descent (Black people) and it is rooted first and foremost in Africa. It’s less concerned with “what could have been” and more concerned with “what is and can/will be”. It acknowledges, grapples with and carries “what has been”.

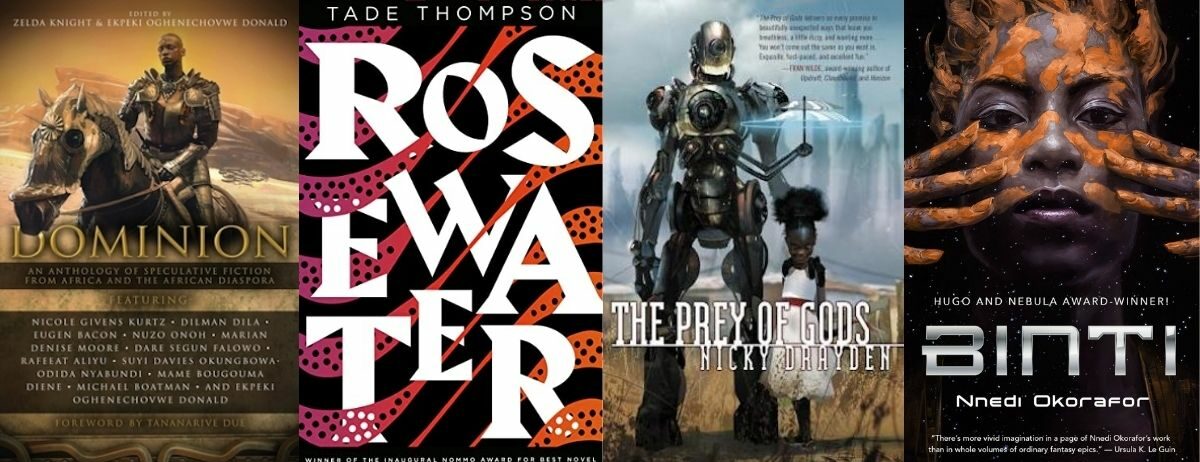

Regarding Black writers, residency and nationality are not as important as the historical and cultural context. Some recent literary examples include some works by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, Tade Thompson, Nicky Drayden and Okorafor. Some of these creatives currently live in an African country (many in Nigeria), while others are the children of immigrants.

Can they work together?

Speculative fiction anthologies that include many Black science fiction writers will feature stories and themes found in Afrofuturism and Africanfuturism. Sometimes these works can come together in a single narrative. For example, on April 19, 2022, Janelle Monáe’s creative universe (built into her discography) is coming together to include Afrofuturist and Africanfuturist writers for an anthology work.

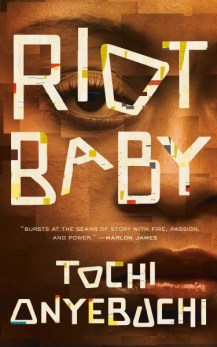

Some writers like Nigerian American writer Tochi Onyebuchi dabble in both, depending on the work. For example, his award-winning novella Riot Baby is a work of Afrofuturism because of its very American perspective, theme, and setting. However, his War Girls series is a work of Africanfuturism as it’s a post-apocalyptic look at another Nigerian Civil War. Readers can approach both stories with little background knowledge. However, understanding anti-Blackness in the U.S. for Riot Baby and Nigerian independence for War Girls shapes each work.

If you’re in the Americas or Europe, you’re more likely to come across Afrofuturism (or its siblings, like Caribbean Futurism) than Africanfuturism. If you want to learn more about these subjects, check out Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture by Ytasha L. Womack, How Long ’til Black Future Month?: Stories by N. K. Jemisin, and the essay Afrofuturism, Africanfuturism, and the Language of Black Speculative Literature by Hope Wabuke.

(image: Chicago Review Press)

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]