Our Books, Our Shelves: Down with Literary Snobbery, Long Live Genre

When I told friends and acquaintances I’d become a fantasy novelist, I was surprised by some of their off-hand comments. First, people assume that the series must be aimed at children or young adults (unspoken: real grown-ups don’t read fantasy). Others tell me they’ve never read a fantasy novel before (unspoken: this genre is below them); or, when they do start the series, they use adjectives like “fun” (unspoken: real literature should not be enjoyable).

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised by these reactions, but everyone imagines their taste is universal, and I’ve always read and loved fantasy.

I’ve entered into this world after decades as a professor of film history. In film, genre films are accepted, lauded. In fact, one of the main avenues by which we teach is through the lens of genre: I’ve taught courses dedicated to westerns, war films, musicals, romantic comedy, and film noir. Watching how a genre develops and changes with the changes in American society and industry practice is fascinating. No one would say of John Ford, “Oh, he just made Westerns,” or of a Hitchcock film, “I never watch thrillers.”

Although genres that traditionally appealed to women—such as “chick flicks” or “weepies” (even their names are dismissive)—have encountered more scoffing than those that appeal to men, no one dismisses genre per se.

As a mass art form film has always had to stay close to audience taste and make money, yet Hollywood did create its own hierarchies. More expensive movies (especially historical epics and prestige adaptations), were presented in limited engagements at the best theaters with higher prices. Often called “road shows,” these films were longer, grander, full of stars and spectacle. Films like Gone With the Wind, Lawrence of Arabia, or Ben Hur won the lion’s share of attention and awards while mysteries and westerns from Monogram or Republic studios were relegated to second feature and B-movie status.

But starting in the 1950s, critics and movie-goers alike began turning away from what the French called “the tradition of quality” and discovering the riches of genre. Robert Warshow wrote two brilliant essays on the gangster and the westerner as particularly American heroes. He writes of Westerns, “It is an art form for connoisseurs, where the spectator derives his pleasure from the appreciation of minor variations with the working out of a pre-established order.” And in the ensuing decades, “prestige films” were thrown over in favor of genre movies.

Far from avoiding genre scripts, our most lauded and powerful directors sought to put their own spin on familiar kinds of stories. No one dismisses the Godfather movies as merely escapist gangster films; no one says that Gattaca or The Handmaid’s Tale aren’t to be taken seriously because they are science fiction. American auteurs from Robert Altman, to Steven Speilberg, to the Coen Brothers, to Kathleen Bigelow have moved from one genre to another, as if eager to test themselves against every popular formula.

Evidently, in literature, hierarchical and class prejudices still hold more sway. I wonder why. Perhaps because penny dreadfuls, dime novels, and pulp magazines were not sold in bookstores, but by street vendors, and their difference in quality, association with lower class education, and cheap thrills were concretized through cheaper paper and lurid design. These associations seem to cling to genre fiction.

At the same time, other systemic forces, including the preferences of schools and colleges, “best of” lists, critics, and prizes have continually elevated “literary fiction.” Books aren’t as expensive to produce as movies; some imprints can specialize in titles designed to win acclaim instead of readers.

A 2012 New Yorker essay politely condemned genre fiction as “escapist” and charged that such books violated the canons of high modernism by being “easy to read.”

This charge makes me think of my favorite passage by the film scholar Gerald Mast, a quote I pass out to most classes. Mast once wrote, “The urge to make and to respond to difficult art is understandable; it links the artistic impulse to its origins in the religious impulse . . . Experiencing this kind of art is like going to church: it may be trying but it is good for the soul. . . . But the opposite kind of art that is easy and fun requires explication because . . . its accessibility can mask its depth, precision, complexity and implications. The apprehension and understanding of art that is fun and easy require not special learning but special sensitivity . . . and special care not to be fooled by those simple surfaces into believing the art is simple.”

In a class I co-taught with a colleague from Psychology, we study the concept of “transportation,” the feeling of getting lost in a story, and its psychological benefits. Transportation/escapism is nothing to sneer at: it encourages us to identify with other people and to garner experiences wider than our own limited lives. Some scholars argue that it has unique moral benefits.

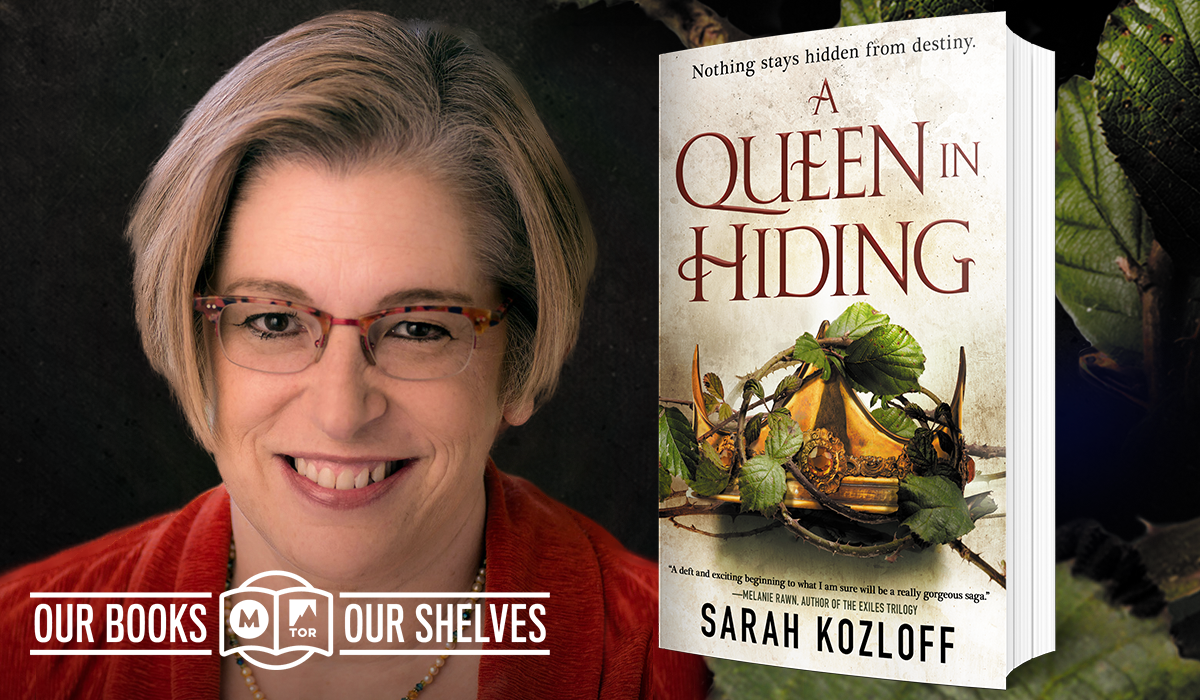

I must confess: it has been a “rock-me-back-on-my-heels” experience to have some of my circle look down on my new endeavor. Most have been too polite to express this baldly, but I sense the undercurrents, especially in the fact that some of my friends bought A Queen in Hiding to be supportive, but have no plans to actually read it!

Appreciating genre fiction requires the same open-mindedness and special sensitivity as appreciating Hollywood movies. It also may require a significant investment of time—a willingness to learn the conventions of the genre so as to grasp the thoughtfulness behind small variations. Literary experts don’t like to be told that their own education is deficient; it is easier to condemn or avoid genre literature. But by avoiding fantasy or detective novels, by dismissively labelling these “beach reads” or “guilty pleasures,” they deprive themselves of genre literatures’ depth, precision, complexity, and implications.

Meanwhile, another “rock-me-back-on-my-heels” experience has been grasping just how much I’m behind in fantasy as a genre. While I was busy grading papers or stretching myself to learn about Mexico’s Golden Age, fantasy has traveled through forking paths and become much more complicated and sophisticated. But I shouldn’t really be surprised. It took me years to understand the dynamics of musicals or war films, and I’m still humbled by the number of movies I haven’t seen or studied. It will take years for me to develop the same level of connoisseurship of fantasy.

But I am more than one step on the route, because I know how much there is I do not know. And I fully accept, as no less a high-culture luminary as Henry James once said, “That the house of fiction has many windows.”

Literary fiction might reside in the cupola, but the ground floor bay windows provide equally lovely views.

(image: Tor Books)

Sarah Kozloff holds an endowed chair as a professor of film history at Vassar College. She worked in the film industry in both television and film before becoming a professor. Kozloff is the author of the Nine Realms Series, beginning with A Queen in Hiding.

Don’t forget to check out the other excellent additions in our exclusive Our Books, Our Shelves column with Tor Books!

- A.K. Larkwood & Tamsyn Muir in Conversation, by A.K Larkwood and Tamsyn Muir

- BE A QUITTER, or HOW TO WRITE THE NOVEL OF YOUR HEART, by K.M. Szpara

- Bestselling Author John Scalzi Talks the End of Everything with John Scalzi

- A Billion Thoughts at Once by TJ Klune

- RIP, IRL: Fandom Has Always Lived Online by Camilla Bruce and Kit Rocha

- Alaya Dawn Johnson on Writing and Book Advocacy with Alaya Dawn Johnson

- On Persistence, Nearly Giving Up, and Writing On by Martha Wells

- The Piss Problem: The Politics Behind Peeing in Space by Mary Robinette Kowal

- What Can Gender Swapping in Stories Tell Us About Ourselves by Kate Elliot

- An Exclusive First Look Behind The Scenes of Bestselling Author V.E. Scwhab’s New Novel, The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue with V.E. Schwab

- A Celebration Of Chaotic Good with Andrea Hairston, S.L. Huang, S.A. Hunt, and Ryan Van Loa

- Our Books, Our Shelves: The Fallacy Of The Universal by Mark Oshiro

- Our Books, Our Shelves: Master of Poisons by Andrea Hairston

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]