When picking up Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X for the first time, the familiarity of the surname and the very Black features of the character on the cover were what drew me to the novel. Because I checked out the audiobook digitally (via the library) and just hit “play” with zero research, I listened, unaware that stanzas and verses broke up the story. I unknowingly connected to a medium I’d never experienced apart and listened to the main character move in a way that was all too familiar.

There’s a whole idiom telling us not to choose books in this way, but we do it anyway, though few will admit it. (Meanwhile, a whole industry exists to influence the reader/customer.) My ignorant trek into The Poet X novel allowed me to connect to this story in meaningful ways and learn that maybe I can read poetry for fun! (Even if only narratively.) I really didn’t know this when I picked up the YA novel, although, in retrospect, thinking about the name a bit more would’ve made it abundantly clear. As a slam poet star, Acevedo’s emotive and rhythmed narration mirrored the main character, Xiomara Batista.

While the story remains interesting, the plot details are not why this book resonates with me. Sure, I had a first crush and those teenage sparks. Though, unlike Xiomara, my life was not bound by the rules of a church or under the supervision of a stay-at-home Dominican mother. I’ve also never been interested in writing fiction. Especially not an intimidating genre like poetry. What I did connect with was the world’s response to Xiomara’s body.

Unhide-able

I am the baby fat that settled into D-cups and swinging hips

so that the boys who called me a whale in middle school

now ask me to send them pictures of myself in thong.

The other girls call me conceited. Ho. Thot. Fast.

Even at only 15, any way that Xiomara moves is perceived as vying for attention. Like in life, many of the adults in the story act as if her experiencing puberty was a reasonable excuse for the prolonged stares from grown men. This isn’t a story about sexual harassment or rape culture. However, the hallmarks are all there from the first poem, “Stoop-Sitting,” onward. She’s expected to cover herself up because existing in her body is drawing attention. Fitting in clothes isn’t just moving comfortably, but distorting any shape.

Many women feel the duality of being simultaneously ignored and yet policed by white supremacist patriarchy. However, being a woman of color, that feeling is amplified because we are exotified. The 2017 study Girlhood Interrupted found this extends to Black girls like Xiomara through adultification and erasure of our childhood. In comparison to their white peers, Black girls were viewed as needing less protection/nurturing. Additionally, Black girls are perceived to be more knowledgeable about sex than their white peers. While this study ranged from ages four to 19, there were discrepancies at every age. As seen with the coverage of Trayvon Martin and other young Black boys, this adultification is also deadly.

Being the first among my peers to develop secondary sex characteristics, I knew exactly what Xiomara felt. Well, not exactly, because I don’t experience Catholic guilt but the rest was there. The same shame and policing of women’s bodies are present in our culture due to sexism. I’ve grown to see this same sentiment appear in attitudes that seek to further police Blackness, sex work, trans-expression, and so much more. Despite releasing when I graduated college, this book feels like a part of my past and my present. That’s why I choose to end this month-long Black History Month series with The Poet X.

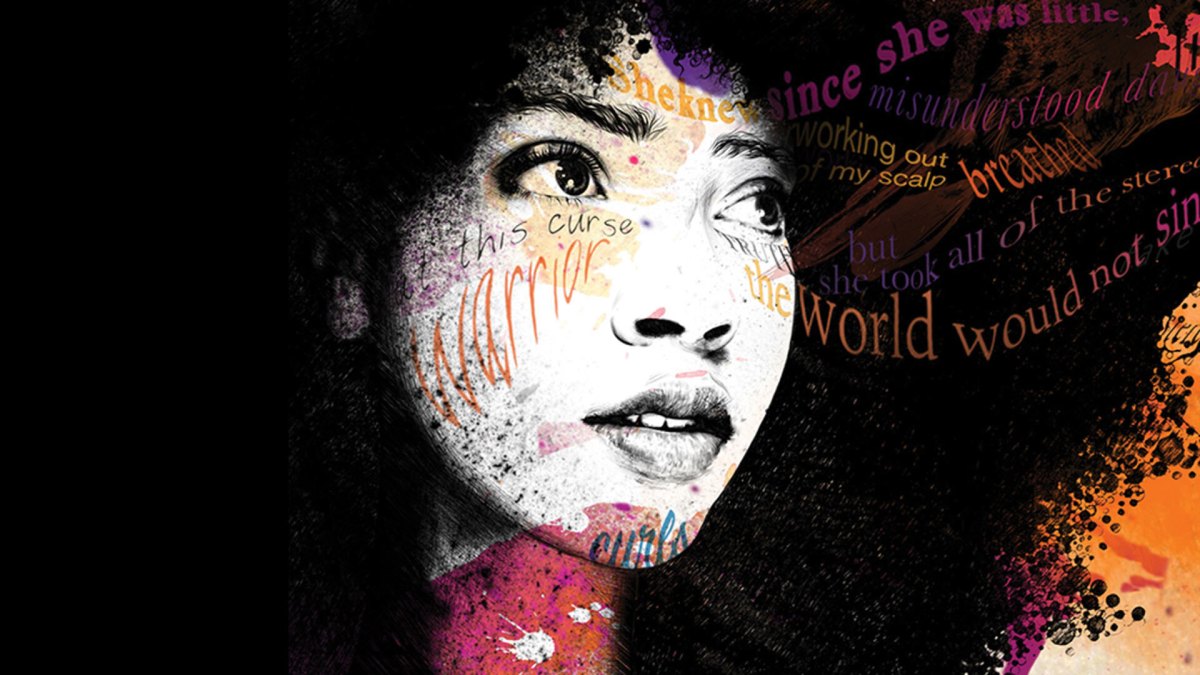

(featured image: Quill Tree Books)

Published: Mar 1, 2023 04:59 pm